Causal inference with ordinal regression

Part 7 of the GLM and causal inference series.

By A. Solomon Kurz

May 21, 2023

We social scientists love collecting ordinal data, such as those from questionnaires using Likert-type items.1 Sometimes we’re lazy and analyze these data as if they were continuous, but we all know they’re not, and the evidence suggests things can go terribly horribly wrong when you do ( Liddell & Kruschke, 2018). Happily, our friends the statisticians and quantitative methodologists have built up a rich analytic framework for ordinal data (see Bürkner & Vuorre, 2019). However, ordinal models make for unique challenges when we want to make causal inferences. In this post, we’ll start grappling with those challenges. Brace yourselves and get ready to get weird.

We need data

In an online study aimed at reducing HIV stigma, Coyne et al. (

2022) used a \(2 \times 2\) Solomon2 four-group design to compare how well two kinds of messages about viral load reduced HIV stigma. The authors also explored the extent to which the difference between the messages depended on pretesting. Whereas a typical Solomon four-group design would compare an active experimental condition with a control condition, you might describe Coyne et al as following a modified Solomon four-group design, given that neither of their messaging conditions are inert controls.

The authors were great, and have provided their raw data files and scripts on the OSF at

https://osf.io/rbq7a/. Here we load the data. ⚠️ For this code to work on your computer, you’ll need to download the Awareness understanding and HIV stigma data.sav file from the OSF, and save that file in a data subfolder within your current working directory for R.

# packages

library(tidyverse)

library(brms)

library(tidybayes)

library(patchwork)

library(marginaleffects)

# adjust the global theme

theme_set(theme_gray(base_size = 12) +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank()))

# load the data and wrangle

coyne2022 <- haven::read_sav(file = "data/Awareness understanding and HIV stigma data.sav") %>%

# remove the first row, which has a participant who reported they were below 18

filter(Age >= 18) %>%

# add a participant number

mutate(id = 1:n(),

# reformat these two variables as factors

TestGroup = as_factor(TestGroup),

MessageGroup = as_factor(MessageGroup)) %>%

# move id to the left

select(id, everything()) %>%

# make dummies for the groups

mutate(pretest = ifelse(TestGroup == "PretestPosttest", 1, 0),

protection = ifelse(MessageGroup == "GainFrame", 1, 0))

# what do we have?

glimpse(coyne2022)

## Rows: 707

## Columns: 45

## $ id <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19…

## $ Consent <chr> "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Y…

## $ Consent2 <chr> "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Y…

## $ Age <dbl> 26, 28, 29, 30, 30, 31, 32, 32, 36, 40, 40, 41, 41, 43, 43, 43, 4…

## $ Gender <chr> "Female", "Female", "Male", "Female", "Female", "Male", "Female",…

## $ Sexuality <chr> "Straight/heterosexual", "Straight/heterosexual", "Straight/heter…

## $ EHLS1 <dbl> 3, 4, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 2,…

## $ EHLS2 <dbl> 4, 4, 4, 3, 4, 1, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 4, 4, 3, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3,…

## $ EHLS3 <dbl> 3, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 4, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 3, 2,…

## $ EHLS4 <dbl> 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 3, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4,…

## $ EHLS5 <dbl> 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 4, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 2,…

## $ EHLS6 <dbl> 3, 4, 3, 2, 3, 2, 4, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3,…

## $ EHLS7 <dbl> 2, 2, 3, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2,…

## $ EHLS8 <dbl> 2, 3, 3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,…

## $ EHLS9 <dbl> 3, 2, 4, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 3, 2, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3,…

## $ EHLS10 <dbl> 3, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3, 4, 2, 2, 4, 2, 2, 4, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 4, 2, 3, 4,…

## $ EHLS11 <dbl> 3, 3, 4, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 1, 3, 2, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3,…

## $ EHLS12 <dbl> 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3,…

## $ StigmaPretest1 <dbl> 2, NA, 2, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 2, NA, 2, 3, 3, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPretest2 <dbl> 5, NA, 4, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 4, NA, 3, 4, 4, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPretest3 <dbl> 5, NA, 4, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 3, NA, 3, 4, 4, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPretest4 <dbl> 5, NA, 5, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 5, NA, 5, 5, 5, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPretest5 <dbl> 3, NA, 2, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 2, NA, 2, 4, 5, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPretest6 <dbl> 3, NA, 2, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 2, NA, 2, 4, 3, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

## $ StigmaPosttest1 <dbl> 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1,…

## $ StigmaPosttest2 <dbl> 5, 2, 4, 1, 2, 2, 5, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 2, 2, 2, 5, 2, 3, 3, 1, 2, 1,…

## $ StigmaPosttest3 <dbl> 5, 3, 4, 1, 2, 2, 5, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 2, 2, 2, 5, 2, 3, 3, 1, 2, 1,…

## $ StigmaPosttest4 <dbl> 5, 4, 5, 3, 5, 5, 5, 4, 5, 3, 4, 4, 1, 5, 3, 5, 4, 3, 3, 2, 5, 4,…

## $ StigmaPosttest5 <dbl> 3, 2, 2, 1, 5, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 4, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1,…

## $ StigmaPosttest6 <dbl> 4, 2, 2, 2, 5, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 4, 2, 4, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 1, 3, 2,…

## $ PerceivedAccuracy <chr> "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "6", "4", "2", "2", "1", "1", "3", "I do…

## $ Understanding <chr> "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", …

## $ Familiarity <chr> "Never", "Never", "Never", "Never", "Never", "Never", "Never", "N…

## $ TestingFrequency <chr> "6-12 months ago", "More than one year ago", "I have never comple…

## $ SocialContactsTesting <chr> "I do not know anybody", "One or two people", "I do not know anyb…

## $ PriorAwareness <chr> "I don't understand this", "I didn't know this already", "I didn'…

## $ TestGroup <fct> PretestPosttest, Posttestonly, PretestPosttest, Posttestonly, Pos…

## $ MessageGroup <fct> GainFrame, LossFrame, GainFrame, GainFrame, GainFrame, LossFrame,…

## $ PerceivedAccuracyKnowledgeofSlogan <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 6, 4, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, NA, 6, 3, 1, 1, 3, 7, 4, 1, 4…

## $ HealthLiteracyTotal <dbl> 36, 37, 41, 31, 36, 31, 42, 35, 30, 37, 31, 32, 41, 26, 35, 30, 3…

## $ StigmaPretestTotal <dbl> 23, NA, 19, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 18, NA, 17, 24, 24, NA, NA, NA, N…

## $ StigmaPosttestTotal <dbl> 24, 15, 19, 9, 21, 13, 20, 15, 17, 13, 16, 23, 11, 17, 12, 19, 16…

## $ UnderstandingKnowledgeofUVL <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

## $ pretest <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,…

## $ protection <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1,…

The coyne2022 data are in the wide format where the data from each participant is found in a single row. The primary substantive independent variable of interest is MessageGroup, which indicates whether each person saw:

- a gain-framed message (

GainFrame, a protection-framed message emphasizing the protective benefits of an undetectable viral load), - or a risk-framed message (

LossFrame, risk-framed message emphasizing the reduction in transmission risk afforded by an undetectable viral load).

The primary methodological independent variable of interest is TestGroup, which indicates whether each person was

- assessed at posttest only (

Posttestonly) - at both pretest and posttest (

PretestPosttest).

The primary dependent variable used by Coyne et al. (

2022) was StigmaPosttestTotal, which is a summary score of six 5-point Likert-type items, StigmaPosttest1 through StigmaPosttest6. Half of the participants also completed the stigma items during the pre-intervention baseline assessment; those item-level responses are saved in the StigmaPretest1 through StigmaPretest6 columns, and their summary score is in the StigmaPretestTotal column.

In this post, we’ll focus instead on the single item StigmaPosttest2, and use it’s analogue StigmaPretest2 as a baseline control. Also, the Solomon four-group design is cool and all, but it would add an unnecessary complication to what will already be an action-packed blog post. So to streamline our analyses just a bit, we’ll

- subset the data to drop all cases without a baseline assessment,

- rename

StigmaPosttest2aspost, - rename

StigmaPretest2aspre, - make a nice

maledummy out of theGenderfactor variable, - make a nice standardized version of

prenamedprez, - remove the unneeded columns,3 and

- save.

coyne2022 <- coyne2022 %>%

filter(pretest == 1) %>%

mutate(male = ifelse(Gender == "Male", 1, 0)) %>%

select(id, male, protection, StigmaPosttest2, StigmaPretest2) %>%

rename(post = StigmaPosttest2,

pre = StigmaPretest2) %>%

mutate(prez = (pre - mean(pre)) / sd(pre))

# what?

glimpse(coyne2022)

## Rows: 353

## Columns: 6

## $ id <int> 1, 3, 9, 11, 12, 13, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 32, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 53, 54, …

## $ male <dbl> 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1,…

## $ protection <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1,…

## $ post <dbl> 5, 4, 3, 3, 4, 2, 2, 1, 3, 3, 5, 3, 3, 5, 1, 3, 2, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 4, 2, 4, 1, 4, 5, 2, 2,…

## $ pre <dbl> 5, 4, 4, 3, 4, 4, 2, 1, 3, 3, 5, 3, 3, 4, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 2, 4, 4, 4, 1, 4, 5, 2, 2,…

## $ prez <dbl> 2.3284981, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 0.5627412, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, -0.3201372, -1.2030156,…

I’m not going to show any pre-model exploratory data-analysis-type plots of the data. In the next section, I’d like us to lean on theory, instead, for things like our priors. The main thing you need to keep in mind is our focal variable post is a 5-point Likert-type item. Here are the levels.

coyne2022 %>%

distinct(post) %>%

arrange(post)

## # A tibble: 5 × 1

## post

## <dbl>

## 1 1

## 2 2

## 3 3

## 4 4

## 5 5

For the post variable, 1 maps to strongly agree and 5 maps to strongly disagree for the question: “I would be comfortable sharing food with someone living with HIV.” Okay. We’re ready to describe and fit our models.

Models

In this blog post, we’ll be using a Bayesian approach. Our two focal models will be a cumulative probit ANOVA, and a cumulative probit ANCOVA. We’ll discuss cumulative logit alternatives later in the post. Frankly, I’m not yet settled on the best notation for models like this. In this post I’ll be mashing up sensibilities from Kruschke ( 2015) and McElreath ( 2015), which which we might express our cumulative probit ANOVA with the formula

$$

\begin{align*} \text{post}_i & \sim \operatorname{Cumulative}(\mathbf p, \mu_i, \alpha) \\ p_j & = \Phi(\tau_j) \\ \mu_i & = 0 + \beta_1 \text{protection}_i \\ \alpha & = 1 \\ \tau_1 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(-0.8416212, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(-0.2533471, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0.2533471, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0.8416212, 1) \\ \beta_1 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, 1), \end{align*}

$$

where \(\mathbf p\) in the top line is a vector of \(J\) probabilities \(\{p_1, p_2, p_3, p_4, p_5 \}\) corresponding to 5 options on the item. With the cumulative probit model, we use the standard normal cumulative distribution as our link function, which is often denoted \(\Phi\). We map those \(J\) probabilities onto \(\Phi\) with \(J - 1\) thresholds, \(\tau_1, \dots, \tau_4\).

For identification purposes, the \(\beta_0\) parameter is fixed to 0, which I have explicitly denoted in the third line of the equation. We have set \(\alpha\) to 1, also for identification purposes. In case you’re not familiar, \(\alpha\) is the discrimination parameter, which is the inverse of \(\sigma\). Bürkner uses this parameterization in brms functions because of its connection to item response theory (see.,

Bürkner, 2020;

Bürkner & Vuorre, 2019).

In this blog post, we’ll include our predictor variables in a linear model for the latent mean \(\mu_i\). In principle, they could be used in other ways, such as with category-specific effects. You can learn about those and other useful alternatives in Bürkner and Vuorre’s nice (

2019) tutorial paper. In our models, we will allow our focal independent variable protectionto influence the model with the \(\beta_1\) parameter.

I have set the priors for our thresholds, \(\tau_1, \dots, \tau_4\), based on a “null” assumption all 5 response options are equally likely. This may not be the best null assumption for all domains, but one has to start somewhere and for the sake of this blog post, it’s as fine a place to start as any other. Here’s how I used that equal-proportion assumption to derive the mean hyperparameters for the thresholds:

tibble(rating = 1:5) %>%

mutate(proportion = 1/5) %>%

mutate(cumulative_proportion = cumsum(proportion)) %>%

mutate(probit_threshold = qnorm(cumulative_proportion))

## # A tibble: 5 × 4

## rating proportion cumulative_proportion probit_threshold

## <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 0.2 0.2 -0.842

## 2 2 0.2 0.4 -0.253

## 3 3 0.2 0.6 0.253

## 4 4 0.2 0.8 0.842

## 5 5 0.2 1 Inf

As is typically the case with ordinal models, we get the final threshold for free; it’s conceptually fixed to \(\infty\). To make these threshold priors weak, I just set their standard deviation hyperparaemters all to 1.

The \(\operatorname{Normal}(0, 1)\) prior on \(\beta_1\) is weakly regularizing. It will allow for a broad range of magnitudes on the latent-mean scale, but rule out obscenely large group differences. You could think of \(\beta_1\) in this model as something like a latent Cohen’s \(d\), and I couldn’t imagine a difference larger than \(d = 2\) for an experiment like this.

Our second model will be a cumulative probit ANCOVA of the form

$$

\begin{align*} \text{post}_i & \sim \operatorname{Cumulative}(\mathbf p, \mu_i, \alpha) \\ p_j & = \Phi(\tau_j) \\ \mu_i & = 0 + \beta_1 \text{protection}_i + \color{blueviolet}{\beta_2 \text{male}_i} + \color{blueviolet}{\beta_3 \text{prez}_i} \\ \alpha & = 1 \\ \tau_1 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(-0.8416212, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(-0.2533471, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0.2533471, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0.8416212, 1) \\ \beta_1, \dots, \beta_3 & \sim \operatorname{Normal}(0, 1), \end{align*}

$$

where we now add the two baseline covariates male and prez. Both \(\beta_2\) and \(\beta_3\) parameters have the same \(\operatorname{Normal}(0, 1)\) prior as our focal parameter \(\beta_1\). Given how our second covariate prez is the standardized baseline version of our post-treatment variable, we might reasonably expect that parameter to be pretty strong. Thus, I could easily see a substantive expert arguing for a prior more like \(\operatorname{Normal}(1, 1)\) for \(\beta_3\). Since that’s not the main point of this blog post, we’ll press forward with my preferred weakly-regularizing default.

Here’s how to fit the two models with brm(). Note the syntax in the family argument. The default is the logit link. You have to manually adjust the link function if you want a cumulative probit model.

# cumulative probit ANOVA

fit1 <- brm(

data = coyne2022,

family = cumulative(probit),

post ~ 1 + protection,

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.8416212, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.2533471, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.2533471, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.8416212, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal(0, 1), class = b)),

cores = 4, seed = 7

)

# cumulative probit ANCOVA

fit2 <- brm(

data = coyne2022,

family = cumulative(probit),

post ~ 1 + protection + male + prez,

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.8416212, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.2533471, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.2533471, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.8416212, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal(0, 1), class = b)),

cores = 4, seed = 7

)

Check the model summaries.

print(fit1)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: post ~ 1 + protection

## Data: coyne2022 (Number of observations: 353)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -0.54 0.09 -0.71 -0.37 1.00 4327 3011

## Intercept[2] 0.45 0.09 0.28 0.62 1.00 4784 3280

## Intercept[3] 1.09 0.10 0.90 1.28 1.00 5048 3323

## Intercept[4] 1.93 0.14 1.66 2.22 1.00 5079 3483

## protection 0.06 0.11 -0.16 0.27 1.00 4842 2868

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

print(fit2)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: post ~ 1 + protection + male + prez

## Data: coyne2022 (Number of observations: 353)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -0.92 0.13 -1.17 -0.67 1.00 3263 3357

## Intercept[2] 0.90 0.13 0.66 1.15 1.00 4773 3374

## Intercept[3] 2.04 0.16 1.74 2.35 1.00 3379 2769

## Intercept[4] 3.37 0.22 2.95 3.83 1.00 3185 2759

## protection 0.03 0.13 -0.22 0.28 1.00 4120 3015

## male 0.26 0.13 0.01 0.50 1.00 4622 3319

## prez 1.39 0.09 1.22 1.57 1.00 2985 2936

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

You’ll note the posteriors for both \(\beta_2\) and \(\beta_3\) in the ANCOVA were clearly positive, and the magnitude for \(\beta_3\) was pretty large, too. It looks like we chose good baseline covariates. Let’s take a more focused look at the summary for \(\beta_1\), the treatment effect, in the two models.

rbind(

fixef(fit1)["protection", ],

fixef(fit2)["protection", ]

) %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(model = c("ANOVA", "ANOCVA")) %>%

select(model, everything())

## model Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

## 1 ANOVA 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

## 2 ANOCVA 0.03045630 0.1262693 -0.2165631 0.2755442

For both models, the \(\beta_1\) posterior is hovering close to 0, which doesn’t bode well for the anti-stigma intervention. But note how with the cumulative probit model, adding predictive baseline covariates increased the posterior SD for \(\beta_1\). Sigh. We’ll talk more about this later.

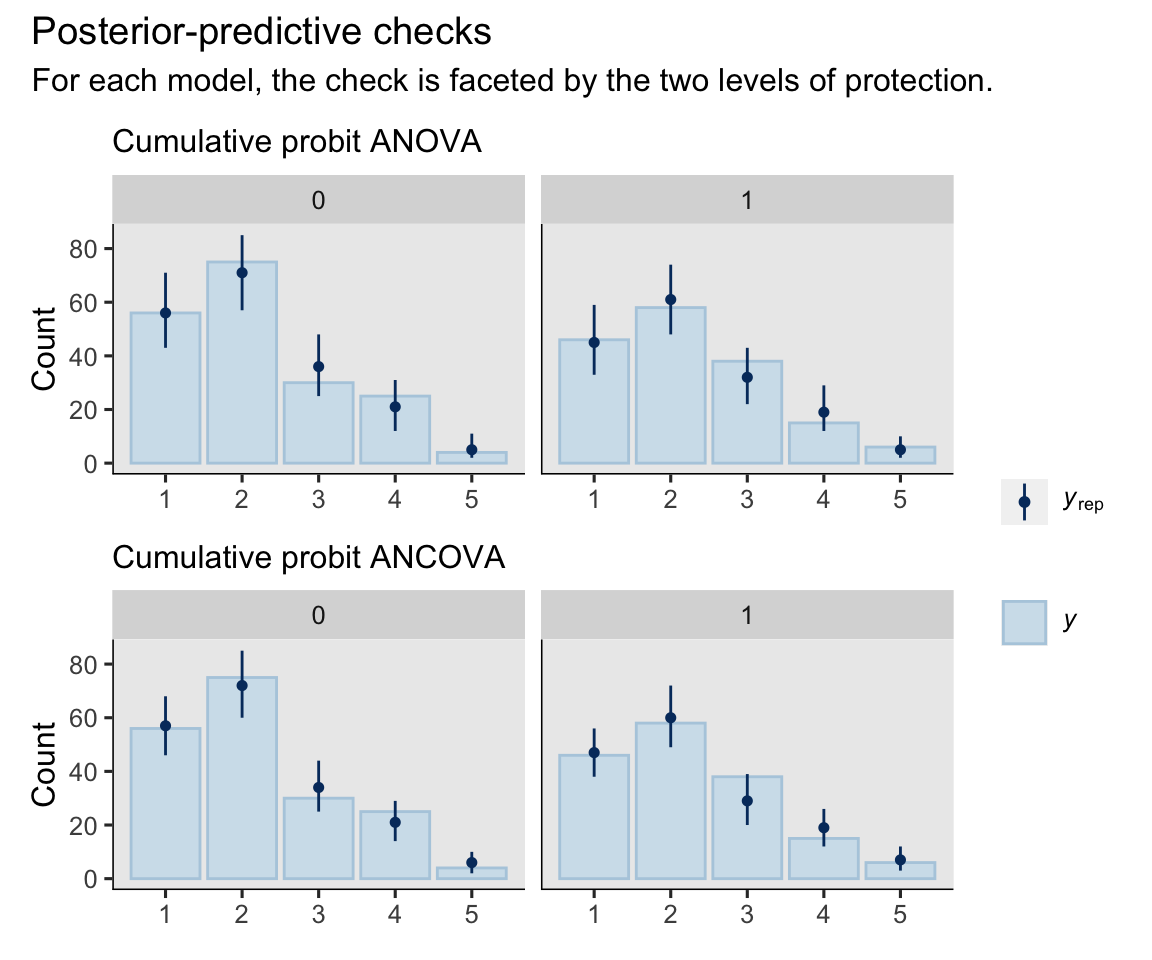

Before we move into theory, we might do a couple quick posterior-predictive checks to see how well the models captured the distributional characteristics of the sample data.

# ANOVA

set.seed(7)

p1 <- pp_check(

fit1,

type = "bars_grouped",

group = "protection",

ndraws = 1000,

linewidth = 1/2,

size = 1/4) +

labs(subtitle = "Cumulative probit ANOVA") +

ylim(0, 85)

# ANCOVA

set.seed(7)

p2 <- pp_check(

fit2,

type = "bars_grouped",

group = "protection",

ndraws = 1000,

linewidth = 1/2,

size = 1/4) +

labs(subtitle = "Cumulative probit ANCOVA") +

ylim(0, 85)

# combine

p1 / p2 +

plot_annotation(title = "Posterior-predictive checks",

subtitle = "For each model, the check is faceted by the two levels of protection.") +

plot_layout(guides = "collect")

Overall, the models did pretty okay.4 It appears the baseline covaraites let the ANCOVA model make more precise predictions, which is just what we’d hope.

Theory overview

Ordinal models can make causal inference trickier than it is with other kinds of models. Volfovsky et al. ( 2015) introduced the topic well:

The first step when attempting any causal analysis is the choice of an estimand, or inferential target, which is the object of interest. When outcomes are continuous, the most commonly studied estimand is the average treatment effect (e.g., see Holland, 1986; Rubin, 1974). However, this quantity is not well defined for non-numeric data as the notion of an average of more than two ordinal values is not well defined. Other measures of centrality might be of interest; for example, the modal difference between treatment and control describes the most common number of categories that are changed due to treatment. (p. 4)

In this post, we will cover two of the approaches I have seen discussed in the literature, and I will offer a third of my own. They will be

\(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\), the average treatment effect for latent potential outcomes ( Volfovsky et al., 2015);\(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\), the difference in probability for each of the\(J\)Likert response options ( Boes, 2013); and\(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\), the average treatment effect after transforming the ordinal model to a continuous scale.

We’ll start off with latent potential outcomes.

Latent potential outcomes and \(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\).

Sometimes we think of ordinal data as coarse measurements of a continuous underlying latent variable (

Bürkner & Vuorre, 2019;

Gelman et al., 2020, Chapter 13). In the case of our cumulative probit models, the latent variable is expressed as a standard normal distribution, which we might call \(Z\).5 Thus instead of the conventional formula

$$ \tau_\text{ATE} = \mathbb E (y_i^1 - y_i^0) = \mathbb E (y_i^1) - \mathbb E (y_i^0), $$

which is expressed in terms of the measured variable \(Y\) itself, we might instead write

$$ \tau_{\color{blueviolet}{z}}^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E ({\color{blueviolet}{z}}_i^1 - {\color{blueviolet}{z}}_i^0) = \mathbb E ({\color{blueviolet}{z}}_i^1) - \mathbb E ({\color{blueviolet}{z}}_i^0), $$

which is expressed in terms of the continuous latent variable underlying the observations of our coarsely-measured ordinal variable.

We can go beyond the simple ANOVA-style of analysis and add baseline covariates. As has been our convention from earlier posts, let \(\mathbf C_i\) stand for a vector of continuous covariates and let \(\mathbf D_i\) stand for a vector of discrete covariates, both of which vary across the \(i\) cases. We can use these to help estimate the ATE with the formula

$$ \tau_z^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i). $$

In words, this means the average treatment effect for the latent variable in the population is the same as the average of each person’s individual treatment effect on the latent variable, computed conditional on their continuous covariates \(\mathbf C_i\) and discrete covariates \(\mathbf D_i\). This, again, is sometimes called standardization or g-computation.

We can also use an alternative approach,

$$ \tau_z^\text{ATE} = \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d), $$

where \(\mathbf C = \mathbf c\) is meant to convey you have chosen particular values \(\mathbf c\) for the variables in the \(\mathbf C\) vector, and \(\mathbf D = \mathbf d\) is meant to convey you have chosen particular values \(\mathbf d\) for the variables in the \(\mathbf D\) vector. Thus when we take \(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\) for our estimand, and we add baseline covariates to the model

$$

\begin{align*} \tau_z^\text{ATE} & = \mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i) \\ & = \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d), \end{align*}

$$

which is a computational convenience we’ve only occasionally enjoyed during this blog series.6

\(\beta_1\) and latent potential outcomes.

Let’s take another focused look at the summary for \(\beta_1\) in the two models.

rbind(

fixef(fit1)["protection", ],

fixef(fit2)["protection", ]

) %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(model = c("ANOVA", "ANOCVA")) %>%

select(model, everything())

## model Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

## 1 ANOVA 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

## 2 ANOCVA 0.03045630 0.1262693 -0.2165631 0.2755442

With the cumulative probit model, adding predictive baseline covariates increased the posterior SD for \(\beta_1\). From an interpretative standpoint,

$$\beta_1 = \tau_z^\text{ATE},$$

the average treatment effect on the scale of the underlying latent variable. Since we are using a cumulative probit model, this is on a standard normal (i.e., \(z\)) scale, and thus this can be interpreted as a latent Cohen’s \(d\). I believe this is the first time we’ve had a model where baseline covariates increased the posterior SD for \(\hat \beta_1\) AND the posterior SD for our causal estimate \(\hat \tau_\text{ATE}\).7 Strange, eh?

\(\mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0)\) without and with covariates.

We will use standardization to compute our estimate for \(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\) via the \(\mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0)\) method. For our brm() models, we can do with with fitted()- add_linpred_draws()-, or marginaleffects-based workflows. We’ll start with a fitted()-based approach. As a first step, we’ll make a predictor grid with each participants’ prez value, and counterfactual values for the independent variable protection.

# update the data grid

nd_id <- coyne2022 %>%

select(id, male, prez) %>%

expand_grid(protection = 0:1) %>%

mutate(row = 1:n())

# what?

glimpse(nd_id)

## Rows: 706

## Columns: 5

## $ id <int> 1, 1, 3, 3, 9, 9, 11, 11, 12, 12, 13, 13, 21, 21, 22, 22, 24, 24, 25, 25, 28, 28, 32, 32,…

## $ male <dbl> 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,…

## $ prez <dbl> 2.3284981, 2.3284981, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 0.5627412, 0.5627412, 1…

## $ protection <int> 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1,…

## $ row <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25…

The trick to getting the counterfactual predictions on the latent-variable scale is to set scale = "linear" within fitted(). Here’s what the first six rows look like, using the default summary = TRUE setting.

fitted(fit1,

newdata = nd_id,

scale = "linear") %>%

head()

## Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

## [1,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

## [2,] 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

## [3,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

## [4,] 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

## [5,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

## [6,] 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

Since the ANOVA model has no way to make use of the baseline covariate prez, the counterfactual estimates are identical across participants, within each level of protection. Now we’ll show the full code necessary for the \(\mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0)\) method. Note how we set summary = FALSE within fitted(). Since this code block is long, I’ll provide more annotation than usual.

# compute the posterior predictions

fitted(fit1,

newdata = nd_id,

scale = "linear",

summary = F) %>%

# convert the results to a data frame

data.frame() %>%

# rename the columns

set_names(pull(nd_id, row)) %>%

# add a numeric index for the MCMC draws

mutate(draw = 1:n()) %>%

# convert to the long format

pivot_longer(-draw) %>%

# convert the row column from the character to the numeric format

mutate(row = as.double(name)) %>%

# join the nd_id predictor grid to the output

left_join(nd_id, by = "row") %>%

# drop two of the unnecessary columns

select(-name, -row) %>%

# convert to a wider format so we can compute the contrast

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = value) %>%

# compute the ATE contrast

mutate(tau = `1` - `0`) %>%

# compute the average ATE value within each MCMC draw

group_by(draw) %>%

summarise(ate = mean(tau)) %>%

# remove the draw index column

select(ate) %>%

# now summarize the ATE across the MCMC draws

summarise(m = mean(ate),

s = sd(ate),

ll = quantile(ate, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(ate, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## m s ll ul

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.0579 0.112 -0.164 0.274

As we said in the last section, \(\beta_1\) is an estimator of \(\tau_Z^\text{ATE}\) for the ordinal ANOVA model. And indeed, these summary values are identical with the summary values for \(\beta_1\). To make the same computation with the avg_comparisons() function, make sure to set type = "link".

# change the marginaleffects default to use the mean, rather than the median

options(marginaleffects_posterior_center = mean)

# compute

avg_comparisons(fit1, type = "link") %>%

data.frame()

## term contrast estimate conf.low conf.high

## 1 protection 1 - 0 0.05788666 -0.1640119 0.2736609

Happily, the summary results from avg_comparisons() match the results we got from fitted(). These methods will work much the same for the cumulative probit ANCOVA fit2. Here’s the fitted() approach.

# this line right here is the only new line

fitted(fit2,

newdata = nd_id,

scale = "linear",

summary = F) %>%

data.frame() %>%

set_names(pull(nd_id, row)) %>%

mutate(draw = 1:n()) %>%

pivot_longer(-draw) %>%

mutate(row = as.double(name)) %>%

left_join(nd_id, by = "row") %>%

select(-name, -row) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = value) %>%

mutate(tau = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(draw) %>%

summarise(ate = mean(tau)) %>%

select(ate) %>%

summarise(m = mean(ate),

s = sd(ate),

ll = quantile(ate, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(ate, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## m s ll ul

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

Again, note how the ANCOVA results have a larger SD compared to the ANOVA results. Sigh. To compute these estimate summaries with the avg_comparisons() function, we just need to specify which variable we want the counterfactual contrast for with the variables argument.

avg_comparisons(fit2, variables = "protection", type = "link") %>%

data.frame()

## term contrast estimate conf.low conf.high

## 1 protection 1 - 0 0.0304563 -0.2165631 0.2755442

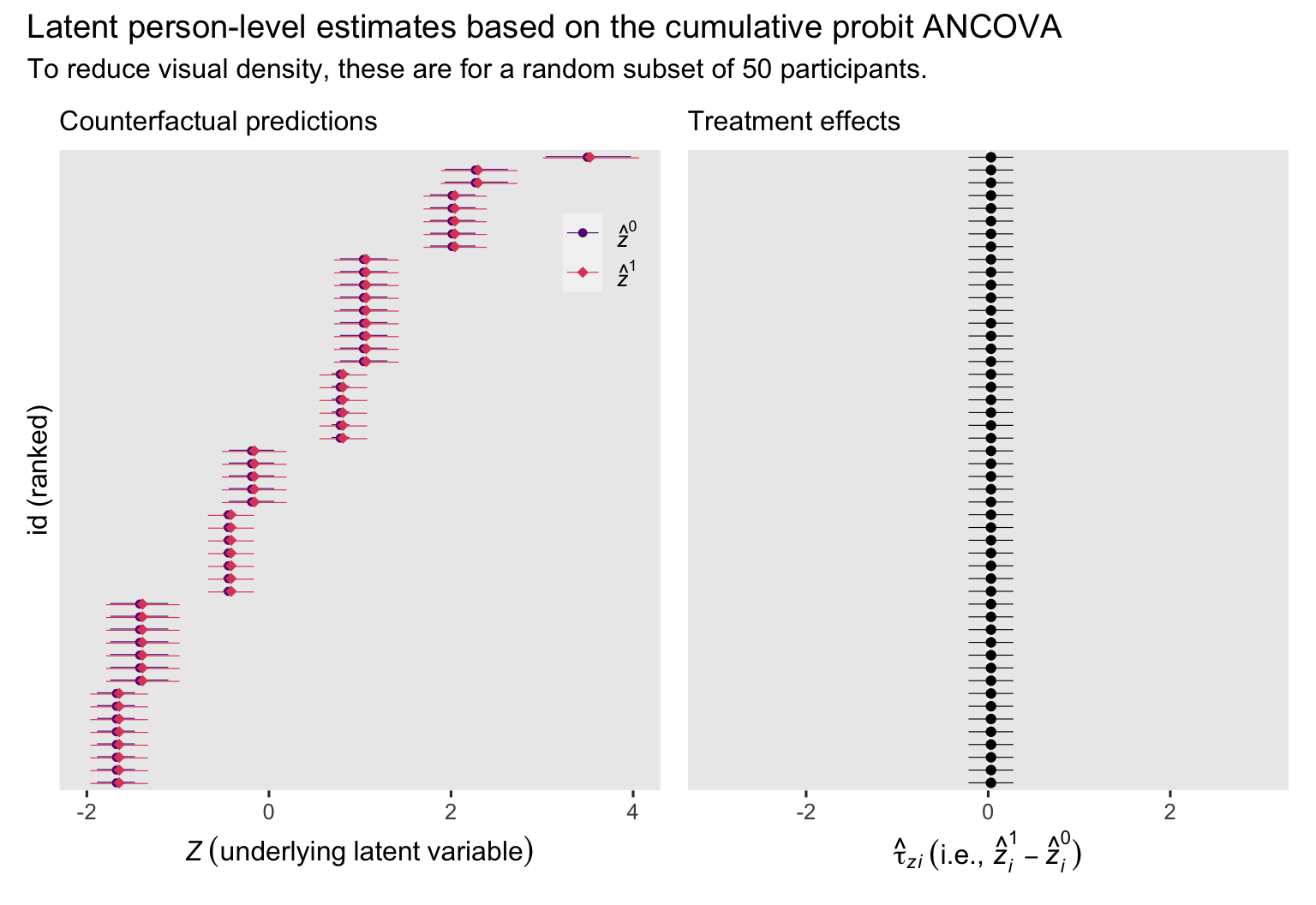

As has become our custom, it might help bring this all down to earth if we make a plot of the person-level counterfactual predictions and their contrasts for the ANCOVA model. Since the full \(N = 353\) data set would make for an overly dense plot, we’ll highlight a random \(n = 50\) subset instead. Here we select our subset, and save their id levels as a vector namedrandom_50.

set.seed(7)

random_50 <- coyne2022 %>%

slice_sample(n = 50) %>%

arrange(id) %>%

pull(id)

# what is this?

print(random_50)

## [1] 9 50 53 69 70 84 113 121 146 151 182 192 213 218 236 246 254 271 305 349 351 356 360 369 380 381

## [27] 401 405 431 452 456 485 497 511 514 543 550 555 568 575 577 582 584 588 590 595 598 636 637 638

Now plot the counterfactual latent predictions, and their contrasts, for our random \(n = 50\) subset. For the sake of practice, we’ll use a tidybayes-based workflow for the predictions. In the past we have relied on the add_epred_draws() function, but in this case since we want the predictions on the latent scale, we use the add_linpred_draws() function instead.

# counterfactual predictions

p1 <- nd_id %>%

filter(id %in% random_50) %>%

add_linpred_draws(fit2) %>%

mutate(y = ifelse(protection == 0, "hat(italic(z))^0", "hat(italic(z))^1")) %>%

group_by(id, y) %>%

mean_qi(.linpred) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = .linpred, y = reorder(id, .linpred), color = y)) +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = .lower, xmax = .upper),

position = position_dodge(width = -0.2),

size = 1/5) +

geom_point(aes(shape = y),

size = 2) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "Counterfactual predictions",

x = expression(italic(Z)~(underlying~latent~variable)),

y = "id (ranked)") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-2, 4)) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(.9, .85))

# treatment effects

p2 <- nd_id %>%

filter(id %in% random_50) %>%

add_linpred_draws(fit2) %>%

ungroup() %>%

select(id, protection, .draw, .linpred) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = .linpred) %>%

mutate(d = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(id) %>%

mean_qi(d) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = d, y = reorder(id, d))) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = "white") +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = .lower, xmax = .upper),

position = position_dodge(width = -0.25),

size = 1/5, color = "black") +

geom_point() +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "Treatment effects",

x = expression(hat(tau)[italic(zi)]~("i.e., "*hat(italic(z))[italic(i)]^1-hat(italic(z))[italic(i)]^0)),

y = NULL) +

xlim(-3, 3)

# combine and entitle

p1 + p2 +

plot_annotation(title = "Latent person-level estimates based on the cumulative probit ANCOVA",

subtitle = "To reduce visual density, these are for a random subset of 50 participants.")

In the case of the cumulative probit ANCOVA, the latent \(z_i^1 - z_i^0\) contrasts are the same across participants, even though their individual \(z_i^1\) and \(z_i^0\) estimates differ. Here’s a closer look at the numeric summaries for the contrasts for our \(n = 50\) subset.

nd_id %>%

filter(id %in% random_50) %>%

add_linpred_draws(fit2) %>%

ungroup() %>%

select(id, protection, .draw, .linpred) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = .linpred) %>%

mutate(d = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(id) %>%

summarise(m = mean(d),

s = sd(d),

ll = quantile(d, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(d, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 50 × 5

## id m s ll ul

## <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 9 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 2 50 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 3 53 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 4 69 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 5 70 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 6 84 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 7 113 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 8 121 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 9 146 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## 10 151 0.0305 0.126 -0.217 0.276

## # ℹ 40 more rows

The contrast for each case \((\tau_{zi})\) is the same as our estimate for the overall estimand \(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\) from above. Each one is also identical with the ANCOVA model’s \(\beta_1\) parameter.

\(\mathbb E (z_i^1) - \mathbb E (z_i^0)\) without and with covariates.

The \(\mathbb E (z_i^1) - \mathbb E (z_i^0)\) method greatly simplifies the computation code. For our cumulative probit ANOVA, we just need a 2-row 1-column predictor grid for the two levels of protection.

# define the predictor grid

nd <- tibble(protection = 0:1)

fitted(fit1,

newdata = nd,

scale = "linear")

## Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

## [1,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.0000000

## [2,] 0.05788666 0.1121175 -0.1640119 0.2736609

Because of the identification constraint that \(\beta_0 = 0\), the group mean \(\mathbb E (z_i^0)\) is exactly zero. This simplifies our contrast of interest like so:

$$

\begin{align*} \tau_z^\text{ATE} & = \mathbb E (z_i^1) - \mathbb E (z_i^0) \\ & = \mathbb E (z_i^1) - 0 \\ & = \mathbb E (z_i^1). \end{align*}

$$

To rehearse the point again, another consequence of this parameterization is \(\mathbb E (z_i^1)\) is the same as the \(\beta_1\) parameter. Thus for our cumulative probit ANOVA

$$ \tau_z^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E (z_i^1) = {\color{blueviolet}{\beta_1}}. $$

The same is true for our cumulative probit ANCOVA. To give a sense, let’s make predictor grid with several different levels of male and prez.

nd_cate <- crossing(

male = 0:1,

prez = -4:4) %>%

mutate(case = 1:n()) %>%

expand_grid(protection = 0:1)

# what?

glimpse(nd_cate)

## Rows: 36

## Columns: 4

## $ male <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

## $ prez <int> -4, -4, -3, -3, -2, -2, -1, -1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, -4, -4, -3, -3, -2, -2, -1,…

## $ case <int> 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 5, 6, 6, 7, 7, 8, 8, 9, 9, 10, 10, 11, 11, 12, 12, 13, 13, 14,…

## $ protection <int> 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1,…

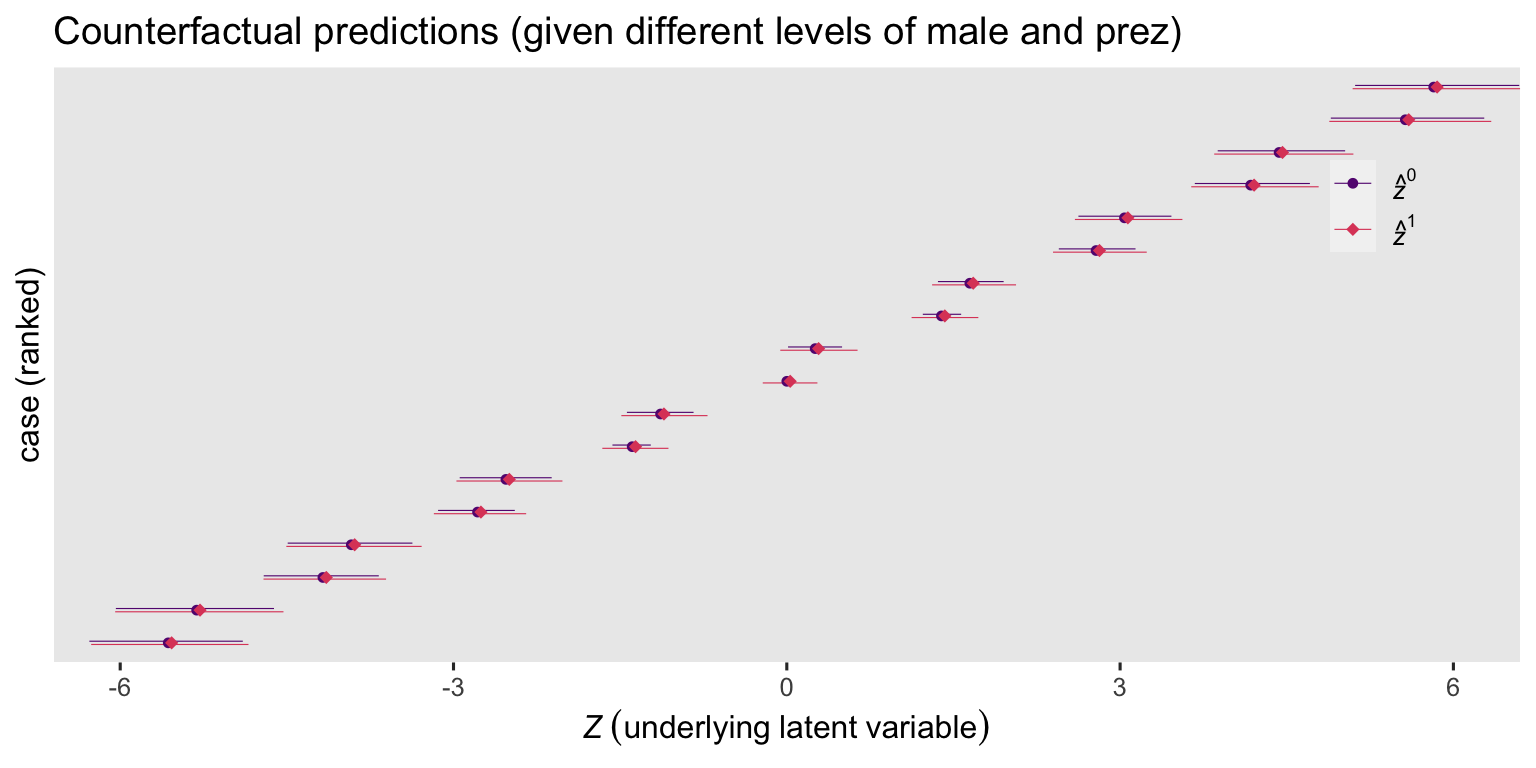

Now we have our nd_cate predictor grid, we’re ready to compute the counterfactual latent predictions with the marginaleffects::predictions() function, and then plot.

predictions(fit2, newdata = nd_cate, type = "link", by = c("case", "protection", "male", "prez")) %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(y = ifelse(protection == 0, "hat(italic(z))^0", "hat(italic(z))^1")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = estimate, y = reorder(case, estimate), color = y)) +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = conf.low, xmax = conf.high),

position = position_dodge(width = -0.2),

size = 1/5) +

geom_point(aes(shape = y),

size = 2) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "Counterfactual predictions (given different levels of male and prez)",

x = expression(italic(Z)~(underlying~latent~variable)),

y = "case (ranked)") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-6, 6)) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(.9, .78))

Even though the predictions vary a lot based on the given values for male and prez, their contrasts are all the same. Here we’ll explicitly compute the contrasts with the comparisons() function.

comparisons(fit2,

newdata = nd_cate,

type = "link",

variables = "protection",

by = c("case", "male", "prez"))

##

## Term Contrast case male prez Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 1 0 -4 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 2 0 -3 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 3 0 -2 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 4 0 -1 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 5 0 0 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 6 0 1 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 7 0 2 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 8 0 3 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 9 0 4 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 10 1 -4 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 11 1 -3 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 12 1 -2 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 13 1 -1 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 14 1 0 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 15 1 1 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 16 1 2 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 17 1 3 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

## protection mean(1) - mean(0) 18 1 4 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

##

## Columns: term, contrast, case, male, prez, estimate, conf.low, conf.high, predicted, predicted_hi, predicted_lo, tmp_idx

For each combination of the baseline covariates male and prez, the result is the same when we take the average over the participants for \(\tau_z^\text{ATE}\). Here’s what that looks like when computed by the avg_comparisons() function.

avg_comparisons(fit2, variables = "protection", type = "link")

##

## Term Contrast Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## protection 1 - 0 0.0305 -0.217 0.276

##

## Columns: term, contrast, estimate, conf.low, conf.high

These are also the same as the summary for the ANCOVA \(\beta_1\) parameter.

fixef(fit2)["protection", ]

## Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

## 0.0304563 0.1262693 -0.2165631 0.2755442

Thus for the cumulative probit ANCOVA

$$

\begin{align*} \tau_z^\text{ATE} & = \mathbb E (z_i^1 - z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i) \\ & =\operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}(z_i^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) \\ & = \beta_1. \end{align*}

$$

Latent wrap-up.

Volfovsky et al’s latent potential outcomes approach has a few attractive properties. It allows researchers to estimate the latent potential outcomes, and their contrasts, for all participants. Because latent variables are numeric, it also allows researchers to compute an ATE on the latent scale. However, latent variable theory might not fit well with all substantive research programs, and some researchers may prefer their effect sizes to have a closer resemblance to the underlying data. Finally, the latent potential outcomes approach does not seem to benefit from baseline covariates, which is something I have not seen acknowledged in the causal inference methodological literature yet.

Conditional probabilities for each response option and \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\).

We can take very different approach by computing a treatment effect defined in terms of the probabilities of the given Likert response options. Boes (

2013) referred to this effect size as \(\Delta_y^\text{ATE}\). Frankly, I find Boes’s notation slightly opaque, and I’m going to refer to his version of the ATE throughout this post as \(\Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{j}}^\text{ATE}\), which is meant to more explicitly connect the effect size with a given level of the \(J\) ordered response options. We might define \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) as

$$ \Delta_j^\text{ATE} = \Pr (y_i^1 = j) - \Pr(y_i^0 = j), \text{ for } j = 1, \dots, J. $$

In words, this is the probability of the \(j\)th Likert response for those in the treatment condition minus the probability of the \(j\)th Likert response for those in the treatment condition. Instead of a single effect size, this will end up returning \(J\) treatment effects. To make that more explicit, we might express the \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) measures for our 5 levels of post as

$$

\begin{align*} \Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{1}}^\text{ATE} & = \Pr (y_i^1 = {\color{blueviolet}{1}}) - \Pr(y_i^0 = {\color{blueviolet}{1}}) \\ \Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{2}}^\text{ATE} & = \Pr (y_i^1 = {\color{blueviolet}{2}}) - \Pr(y_i^0 = {\color{blueviolet}{2}}) \\ \Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{3}}^\text{ATE} & = \Pr (y_i^1 = {\color{blueviolet}{3}}) - \Pr(y_i^0 = {\color{blueviolet}{3}}) \\ \Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{4}}^\text{ATE} & = \Pr (y_i^1 = {\color{blueviolet}{4}}) - \Pr(y_i^0 = {\color{blueviolet}{4}}) \\ \Delta_{\color{blueviolet}{5}}^\text{ATE} & = \Pr (y_i^1 = {\color{blueviolet}{5}}) - \Pr(y_i^0 = {\color{blueviolet}{5}}). \end{align*}

$$

Since our ordinal models return a \(\mathbf p\) vector of probabilities, \(\{p_1, p_2, p_3, p_4, p_5 \}\), we could also express this in the more compact notation of

$$ \Delta_j^\text{ATE} = {\color{blueviolet}{p_j^1 - p_j^0}}, \text{ for } j = 1, \dots, J. $$

Further, since our regression format will also allow us to compute person-specific counterfactual estimates for \(p_{ij}^1\) and \(p_{ij}^0\), we can expand the framework to

$$ \Delta_j^\text{ATE} = {\color{blueviolet}{\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0)}} = p_j^1 - p_j^0, $$

where \(p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0\) is the counterfactual person-specific difference in probability for a given Likert response option, based on whether they were in treatment or control.

We can go beyond the simple ANOVA-style of analysis and add baseline covariates. Let \(\mathbf C_i\) stand for a vector of continuous covariates and \(\mathbf D_i\) stand for a vector of discrete covariates, both of which vary across the \(i\) cases. We can use these to help estimate \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) with the formula,

$$

\Delta_j^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i).

$$

In words, we can compute average treatment effect of the probability difference of observing a particular Likert response with and without the treatment \((\Delta_j^\text{ATE})\) by averaging all the person-specific probability differences of observing a particular Likert response with and without the treatment \((p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0)\), computed conditional on their continuous covariates \(\mathbf C_i\) and discrete covariates \(\mathbf D_i\). We accomplish this averaging by the standardization or g-computation methods we’ve come to know and love. However, as has been the case in other contexts were we used a link function,

$$ {\color{blueviolet}{\Delta_j^\text{CATE}}} = \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) , $$

where \(\mathbf C = \mathbf c\) is meant to convey you have chosen particular values \(\mathbf c\) for the variables in the \(\mathbf C\) vector, and \(\mathbf D = \mathbf d\) is meant to convey you have chosen particular values \(\mathbf d\) for the variables in the \(\mathbf D\) vector. Thus when we add covariates into the model

$$ \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i) \text{ } {\color{blueviolet}{\neq}} \text{ } \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - \mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^0\mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d), $$

and thus

$$ \Delta_j^\text{ATE} \neq \Delta_j^\text{CATE}. $$

Okay, let’s move into application.

\(\beta_1\) and \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\).

To my knowledge, there is no way to compute \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) based with the \(\beta_1\) parameter alone. This method requires we use the parameters from the full ordinal model. If there’s been one message throughout this blog series, it’s that one naïvely interprets \(\beta_1\) at one’s own peril. So what is \(\beta_1\) within the context of the estimand \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\)? It’s one small cog in a large glorious machine. Dont’ get caught up on the cogs, friends.

\(\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0)\) without and with covariates.

We will use standardization to compute our estimate for \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) via the \(\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0)\) method. For our brm() models, we can do with with fitted()- add_epred_draws()-, or marginaleffects-based workflows. However, I recommend against using fitted() for computing the \(p_{ij}\) estimates from ordinal models; it makes for long complicated code. Instead, here we’ll jump straight to an add_epred_draws()-based workflow. We’ll continue using our nd_id predictor grid. Here are what the first 6 rows of the output look like for our cumulative probit ANOVA fit1:

# compute and save

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id <- nd_id %>%

add_epred_draws(fit1) %>%

ungroup()

# show the first 6 rows

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 11

## id male prez protection row .row .chain .iteration .draw .category .epred

## <int> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <fct> <dbl>

## 1 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 1 1 0.294

## 2 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 2 1 0.313

## 3 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 3 1 0.262

## 4 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 4 1 0.267

## 5 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 5 1 0.329

## 6 1 0 2.33 0 1 1 NA NA 6 1 0.290

Note the new .category column, which marks the five Likert response options for the outcome variable post, ranging from 1 to 5 in the output. The .epred column is the conditional probability for each of those response options, for a given participant at a given counterfactual level of protection, and for a given MCMC draw. As a consequence, the full output is very long at 14,120,000 rows. That is

$$14{,}120{,}000 \text{ rows} = 5 \text{ ratings}\times 353 \text{ cases} \times 2 \text{ levels of protection} \times 4000 \text{ MCMC draws}.$$

Here’s how to group and summarize these results to compute the summaries for the \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) estimates.

# contrasts

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

# subset the columns

select(id, protection, .draw, .category, .epred) %>%

# convert to a wider format

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = .epred) %>%

# compute the contrasts

mutate(`1 - 0` = `1` - `0`) %>%

# average the contrasts over the cases

group_by(.draw, .category) %>%

summarise(`1 - 0` = mean(`1 - 0`)) %>%

# now summarize the category-level contrasts

group_by(.category) %>%

summarise(p = mean(`1 - 0`),

sd = sd(`1 - 0`),

ll = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .975))

## `summarise()` has grouped output by '.draw'. You can override using the `.groups` argument.

## # A tibble: 5 × 5

## .category p sd ll ul

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 -0.0195 0.0380 -0.0926 0.0552

## 2 2 -0.00165 0.00390 -0.0113 0.00500

## 3 3 0.00797 0.0155 -0.0225 0.0382

## 4 4 0.00920 0.0181 -0.0268 0.0450

## 5 5 0.00397 0.00792 -0.0110 0.0203

Now compare those results with those from our cumulative probit ANCOVA, fit2.

# compute and save

fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id <- nd_id %>%

add_epred_draws(fit2) %>%

ungroup()

# summarize

fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

select(id, protection, .draw, .category, .epred) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = .epred) %>%

mutate(`1 - 0` = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(.draw, .category) %>%

summarise(`1 - 0` = mean(`1 - 0`)) %>%

group_by(.category) %>%

summarise(p = mean(`1 - 0`),

sd = sd(`1 - 0`),

ll = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .975))

## `summarise()` has grouped output by '.draw'. You can override using the `.groups` argument.

## # A tibble: 5 × 5

## .category p sd ll ul

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 -0.00617 0.0257 -0.0564 0.0438

## 2 2 0.000452 0.00217 -0.00403 0.00483

## 3 3 0.00186 0.00773 -0.0130 0.0171

## 4 4 0.00236 0.00990 -0.0171 0.0222

## 5 5 0.00150 0.00621 -0.0104 0.0140

It might be hard to catch, but the ANCOVA-based \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) estimates are more precise, as indicated by their smaller posterior SD’s. Happily, we can compute these same estimates with much thriftier syntax with the handy avg_comparisons() function.

avg_comparisons(fit1, variables = "protection") # ANOVA

##

## Group Term Contrast Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## 1 protection 1 - 0 -0.01948 -0.0926 0.0552

## 2 protection 1 - 0 -0.00165 -0.0113 0.0050

## 3 protection 1 - 0 0.00797 -0.0225 0.0382

## 4 protection 1 - 0 0.00920 -0.0268 0.0450

## 5 protection 1 - 0 0.00397 -0.0110 0.0203

##

## Columns: group, term, contrast, estimate, conf.low, conf.high

avg_comparisons(fit2, variables = "protection") # ANCOVA

##

## Group Term Contrast Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## 1 protection 1 - 0 -0.006169 -0.05639 0.04380

## 2 protection 1 - 0 0.000452 -0.00403 0.00483

## 3 protection 1 - 0 0.001857 -0.01297 0.01706

## 4 protection 1 - 0 0.002356 -0.01712 0.02221

## 5 protection 1 - 0 0.001503 -0.01039 0.01399

##

## Columns: group, term, contrast, estimate, conf.low, conf.high

It might help clarify what we’ve been computing and summarizing if we make a couple plots. Since the conditional probabilities are the same across participants in the ANOVA model, we’ll jump straight to the cumulative probit ANCOVA. Earlier in the post, we used data from an \(n = 50\) subset. Given how we how have 10 counterfactual estimates for each case, we’ll want to use an even smaller \(n = 20\) subset.

# define the random 20 cases

set.seed(7)

random_20 <- coyne2022 %>%

slice_sample(n = 20) %>%

arrange(id) %>%

pull(id)

# what?

print(random_20)

## [1] 50 53 121 192 218 246 271 305 351 381 401 431 456 550 555 575 582 595 598 637

Next we’ll need to make an index for rank ordering the cases. Since we’ll be faceting over the 5 levels of \(J\), we’ll just want to rank order for one of those levels. I choose \(j = 1\).

id_ranks <- predictions(

fit2,

newdata = nd_id %>% filter(id %in% random_20),

by = c("protection", "group", "id")) %>%

data.frame() %>%

filter(group == 1, protection == 0) %>%

arrange(estimate) %>%

mutate(rank = 1:n()) %>%

select(id, rank)

# what is this?

glimpse(id_ranks)

## Rows: 20

## Columns: 2

## $ id <int> 192, 555, 121, 271, 381, 431, 351, 582, 53, 218, 246, 401, 456, 50, 598, 637, 305, 550, 575, 595

## $ rank <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

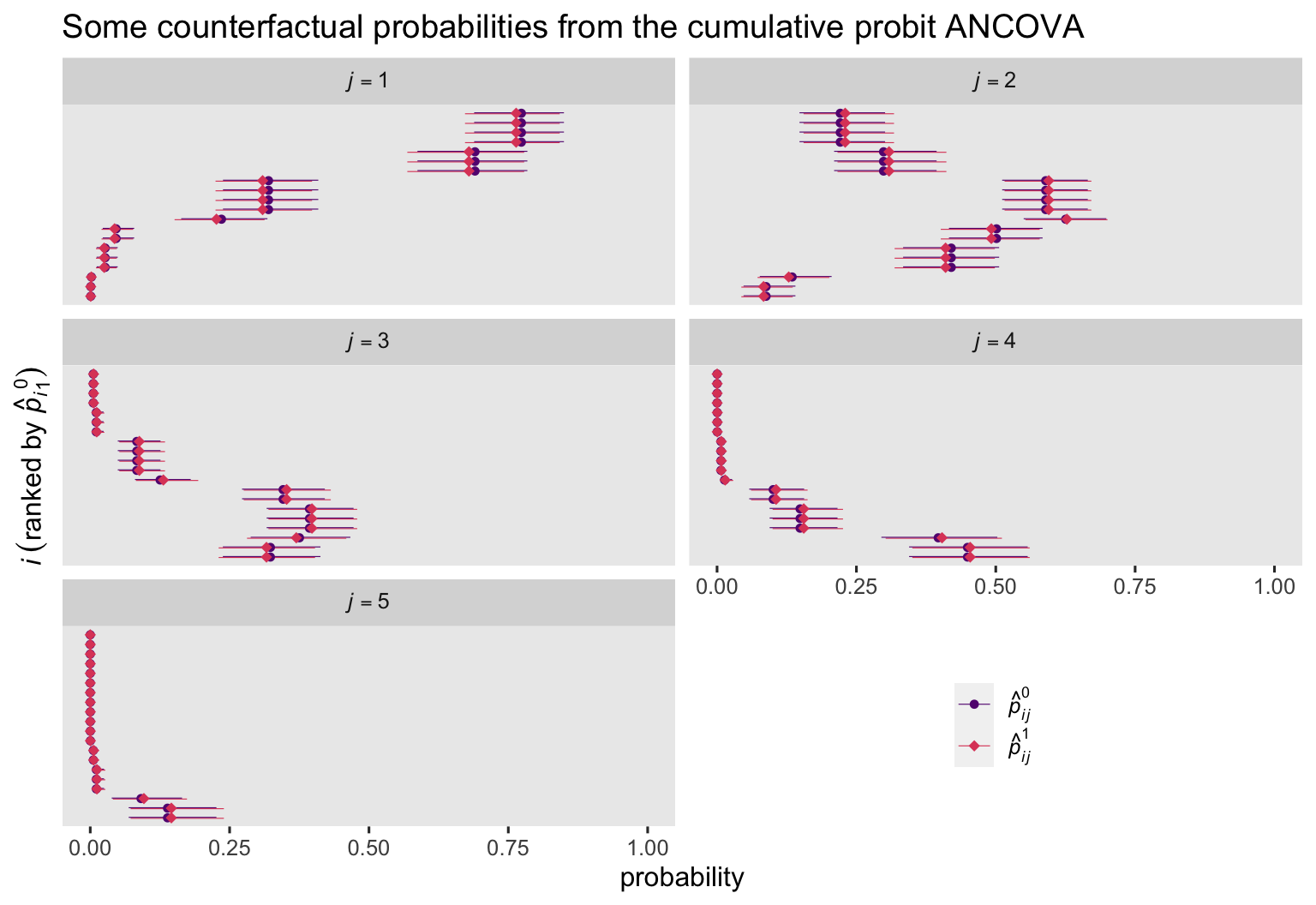

Now we’re finally ready to plot those \(p_{ij}^1\) and \(p_{ij}^0\) estimates for our \(n = 20\) subset.

predictions(fit2,

newdata = nd_id %>% filter(id %in% random_20),

by = c("protection", "group", "id")) %>%

data.frame() %>%

left_join(id_ranks, by = "id") %>%

mutate(protection = ifelse(protection == 0, "hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^0", "hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^1"),

j = str_c("italic(j)==", group)) %>%

# plot!

ggplot(aes(x = estimate, y = rank)) +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = conf.low, xmax = conf.high, color = protection),

position = position_dodge(width = -0.2),

size = 1/5) +

geom_point(aes(color = protection, shape = protection),

size = 2) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_x_continuous(limits = c(0, 1)) +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "Some counterfactual probabilities from the cumulative probit ANCOVA",

x = "probability",

y = expression(italic(i)~(ranked~by~hat(italic(p))[italic(i)][1]^0))) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(.75, .15)) +

facet_wrap(~ j, labeller = label_parsed, ncol = 2)

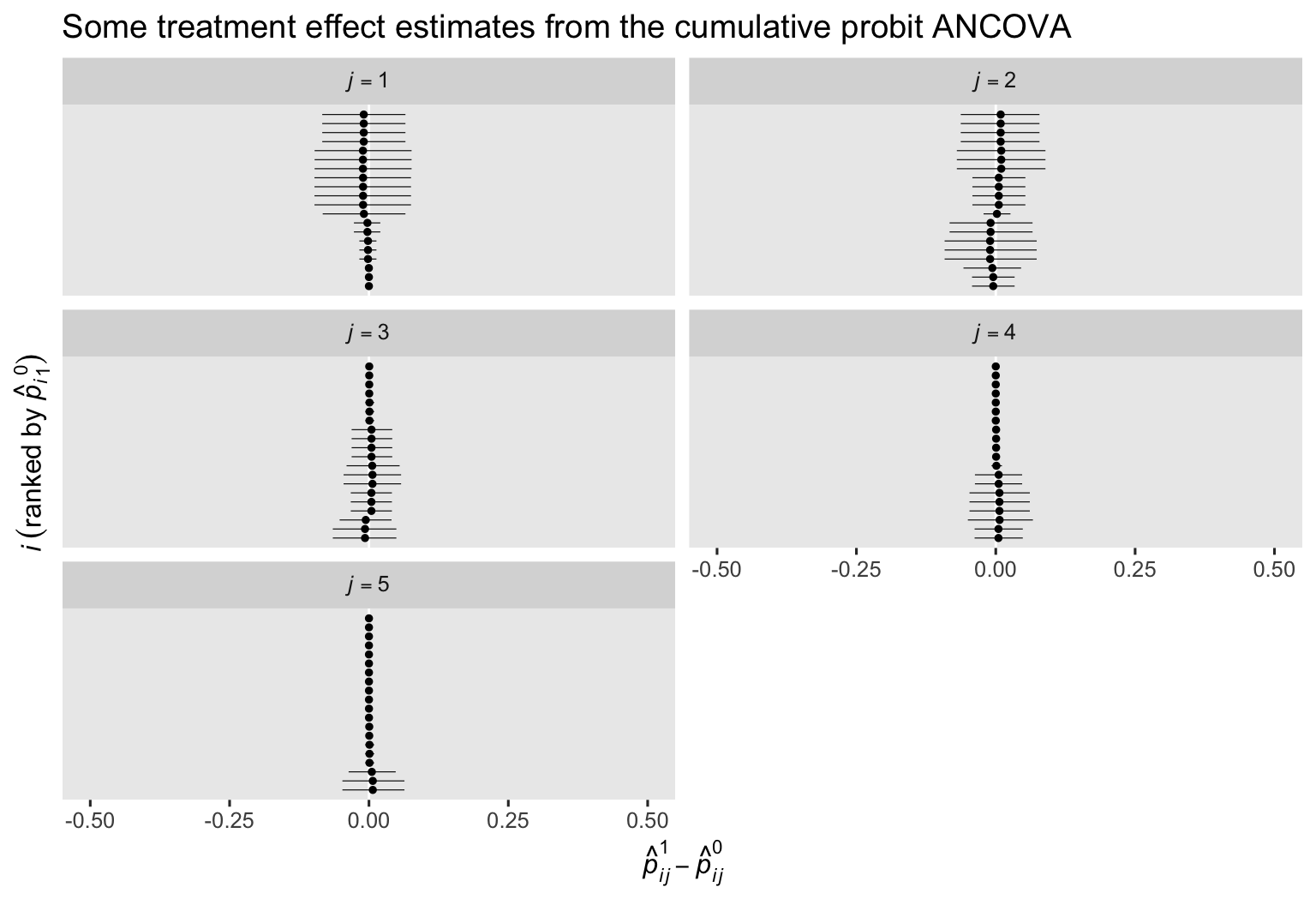

Here’s a plot of the corresponding \(p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0\) contrasts.

comparisons(fit2,

newdata = nd_id %>% filter(id %in% random_20),

variable = "protection",

by = c("group", "id")) %>%

data.frame() %>%

left_join(id_ranks, by = "id") %>%

mutate(j = str_c("italic(j)==", group)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = estimate, xmin = conf.low, xmax = conf.high, y = rank)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = "white") +

geom_interval(size = 1/5) +

geom_point(size = 1) +

scale_x_continuous(limits = c(-0.5, 0.5)) +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "Some treatment effect estimates from the cumulative probit ANCOVA",

x = expression(hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^1-hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^0),

y = expression(italic(i)~(ranked~by~hat(italic(p))[italic(i)][1]^0))) +

facet_wrap(~ j, labeller = label_parsed, ncol = 2)

Here we see that even though the \(p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0\) contrasts are pretty small across all cases, the estimates differ in terms of their posterior means (dots) and widths of their 95% intervals (horizontal lines).

\(p_j^1 - p_j^0\) without covariates.

For the \(p_j^1 - p_j^0\) method, we’ll continue to rely on the add_epred_draws()- and marginaleffects-based workflows. For our ANOVA model, we can continue using the simple nd predictor grid, which we’ll reproduce here just in case you forgot which one what was. Here are what the first 6 rows of the output look like for our cumulative probit ANOVA fit1:

# define the predictor grid

nd <- tibble(protection = 0:1)

# compute and save

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_group <- nd %>%

add_epred_draws(fit1) %>%

ungroup()

# show the first 6 rows

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_group %>%

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 7

## protection .row .chain .iteration .draw .category .epred

## <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <fct> <dbl>

## 1 0 1 NA NA 1 1 0.294

## 2 0 1 NA NA 2 1 0.313

## 3 0 1 NA NA 3 1 0.262

## 4 0 1 NA NA 4 1 0.267

## 5 0 1 NA NA 5 1 0.329

## 6 0 1 NA NA 6 1 0.290

As we’re now averaging over participants, the add_epred_draws() output is only 40,000 rows long. Here’s how to summarize the \(J\) conditional probabilities and their contrasts.

# conditional probabilities

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_group %>%

# now summarize the category-level probabilities, by protection

group_by(protection, .category) %>%

summarise(p = mean(.epred),

sd = sd(.epred),

ll = quantile(.epred, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(.epred, probs = .975))

## `summarise()` has grouped output by 'protection'. You can override using the `.groups` argument.

## # A tibble: 10 × 6

## # Groups: protection [2]

## protection .category p sd ll ul

## <int> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0 1 0.296 0.0302 0.240 0.357

## 2 0 2 0.376 0.0264 0.326 0.427

## 3 0 3 0.190 0.0223 0.148 0.234

## 4 0 4 0.111 0.0187 0.0768 0.150

## 5 0 5 0.0281 0.00918 0.0134 0.0487

## 6 1 1 0.277 0.0317 0.218 0.342

## 7 1 2 0.374 0.0264 0.324 0.425

## 8 1 3 0.198 0.0233 0.155 0.245

## 9 1 4 0.120 0.0198 0.0836 0.162

## 10 1 5 0.0321 0.0104 0.0149 0.0552

# contrasts

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_group %>%

select(protection, .draw, .category, .epred) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = .epred) %>%

mutate(`1 - 0` = `1` - `0`) %>%

# now summarize the category-level probabilities, by protection

group_by(.category) %>%

summarise(p = mean(`1 - 0`),

sd = sd(`1 - 0`),

ll = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(`1 - 0`, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 5 × 5

## .category p sd ll ul

## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 -0.0195 0.0380 -0.0926 0.0552

## 2 2 -0.00165 0.00390 -0.0113 0.00500

## 3 3 0.00797 0.0155 -0.0225 0.0382

## 4 4 0.00920 0.0181 -0.0268 0.0450

## 5 5 0.00397 0.00792 -0.0110 0.0203

You can get the same results for the posterior means and 95% intervals with the predictions() and comparisons() functions.

# conditional probabilities

predictions(fit1, newdata = nd, by = c("protection", "group"))

##

## Group protection Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## 1 0 0.2960 0.2403 0.3566

## 1 1 0.2765 0.2184 0.3418

## 2 0 0.3758 0.3256 0.4269

## 2 1 0.3742 0.3236 0.4245

## 3 0 0.1896 0.1478 0.2342

## 3 1 0.1975 0.1550 0.2447

## 4 0 0.1105 0.0768 0.1504

## 4 1 0.1197 0.0836 0.1622

## 5 0 0.0281 0.0134 0.0487

## 5 1 0.0321 0.0149 0.0552

##

## Columns: group, protection, estimate, conf.low, conf.high

# conditional probability contrasts

comparisons(fit1, newdata = nd, by = "group")

##

## Group Term Contrast Estimate 2.5 % 97.5 %

## 1 protection mean(1) - mean(0) -0.01948 -0.0926 0.0552

## 2 protection mean(1) - mean(0) -0.00165 -0.0113 0.0050

## 3 protection mean(1) - mean(0) 0.00797 -0.0225 0.0382

## 4 protection mean(1) - mean(0) 0.00920 -0.0268 0.0450

## 5 protection mean(1) - mean(0) 0.00397 -0.0110 0.0203

##

## Columns: group, term, contrast, estimate, conf.low, conf.high, predicted, predicted_hi, predicted_lo, tmp_idx

This method for estimating \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\), however, is only available for the ANOVA model. Once you add baseline covariates to the model, the \((p_j^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - (p_j^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d)\) method can only return some version of \(\Delta_j^\text{CATE}\), which isn’t the estimand of interest in this blog series.8

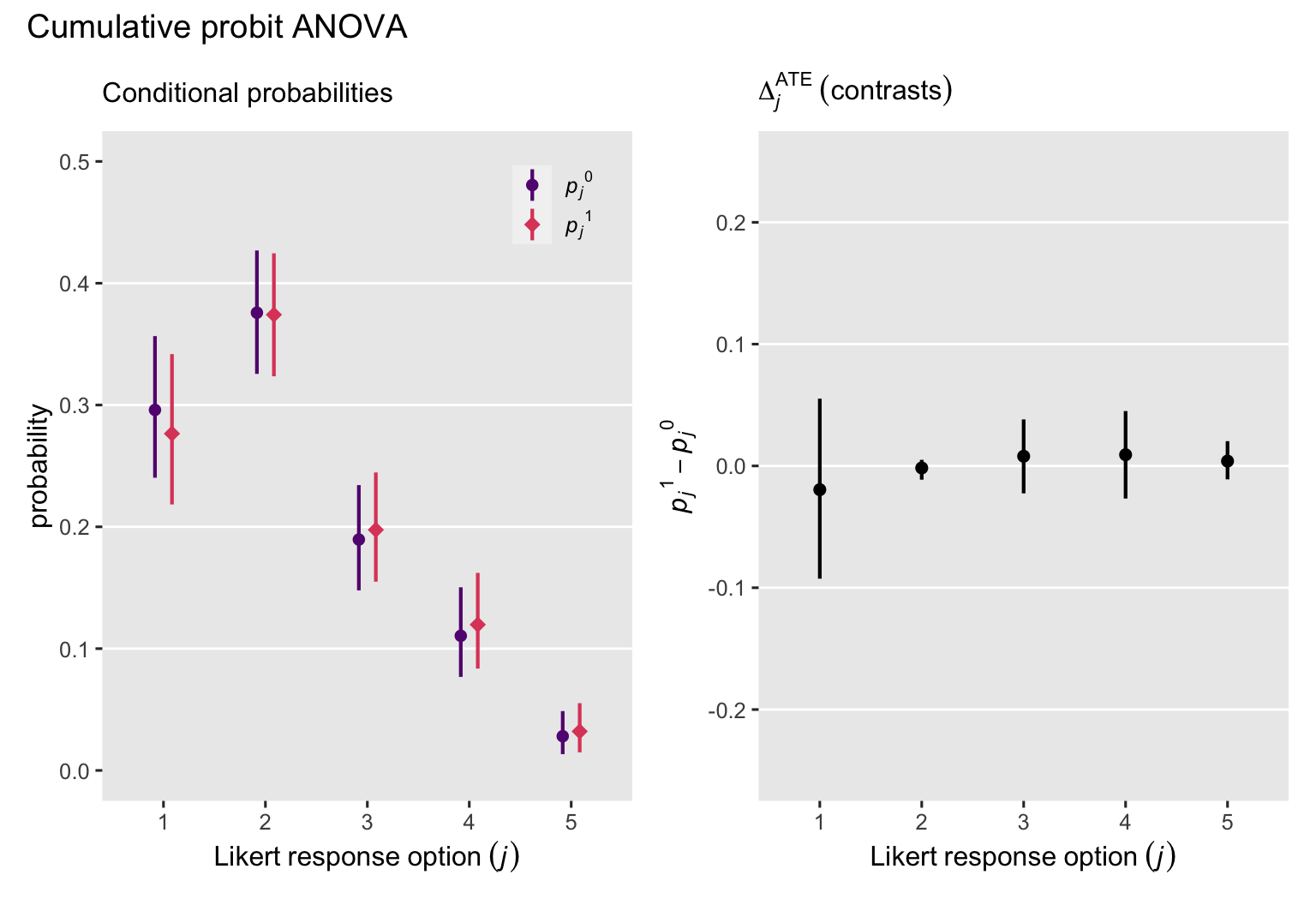

Before we move on from this section, we might depict these counterfactual probabilities and their contrasts with a plot. We’ll continue on with the compact predictions() and comparisons() syntax.

# conditional probabilities

p1 <- predictions(fit1, newdata = nd) %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(protection = ifelse(protection == 0, "italic(p[j])^0", "italic(p[j])^1")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = group, y = estimate, ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high,

color = protection)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 1:4 / 10, color = "white") +

geom_linerange(linewidth = 3/4, position = position_dodge(width = 1/3)) +

geom_point(aes(shape = protection),

position = position_dodge(width = 1/3),

size = 3) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_y_continuous("probability", limits = c(0, 0.5)) +

labs(subtitle = "Conditional probabilities",

x = expression(Likert~response~option~(italic(j)))) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(0.85, 0.9))

# contrasts

p2 <- comparisons(fit1, newdata = nd, by = "group") %>%

data.frame() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = group, y = estimate, ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = -2:2 / 10, color = "white") +

geom_pointrange(linewidth = 3/4, size = 1/3) +

scale_y_continuous(expression(italic(p[j])^1-italic(p[j])^0), limits = c(-0.25, 0.25)) +

labs(subtitle = expression(Delta[italic(j)]^{ATE}~(contrasts)),

x = expression(Likert~response~option~(italic(j))))

# combine and entitle

p1 + p2 + plot_annotation(title = "Cumulative probit ANOVA")

That is, the posteriors for our \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) contrasts are all pretty small. The intervention was not effective.

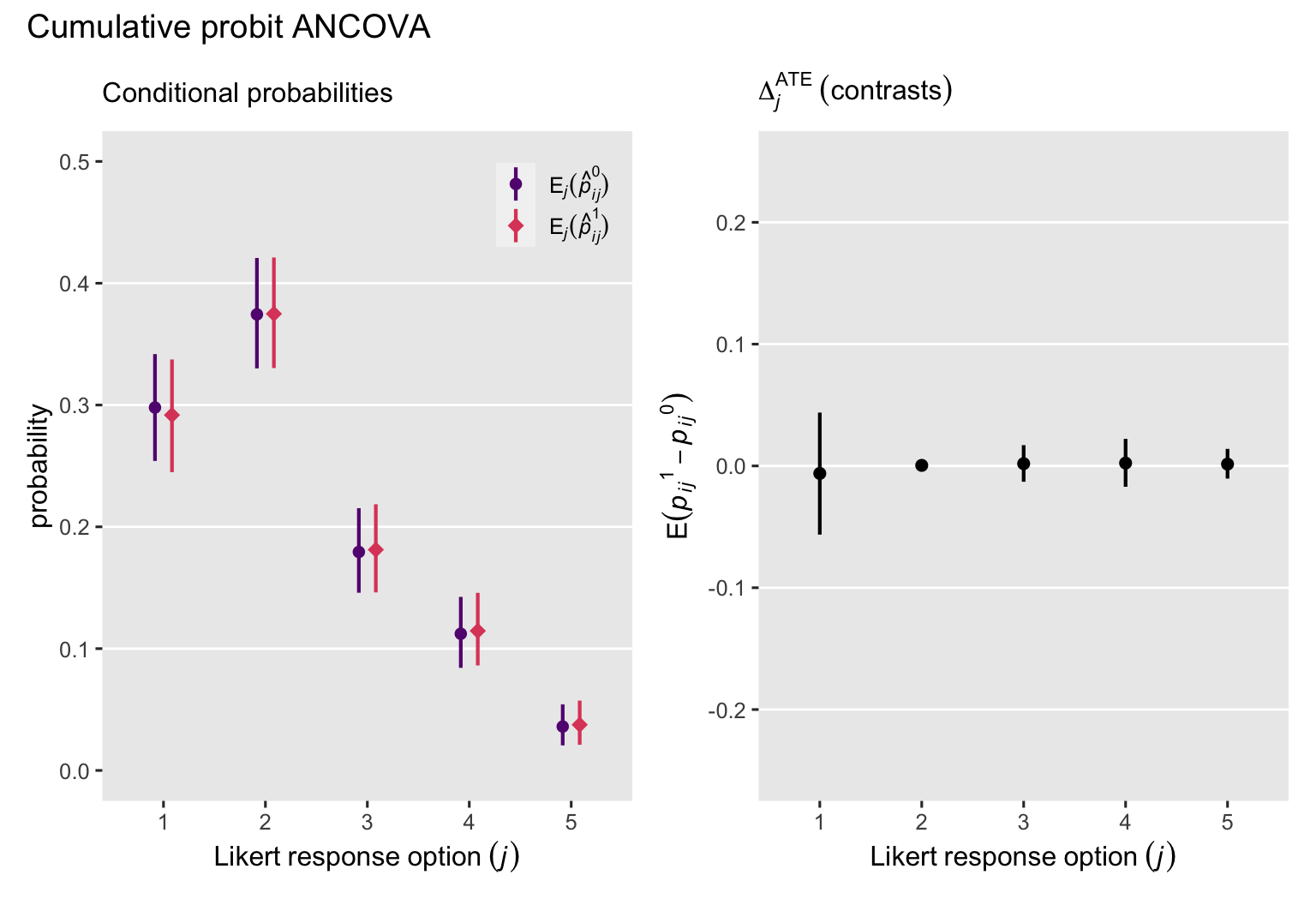

Although we can’t make the corresponding plot with the \((p_j^1 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d) - (p_j^0 \mid \mathbf C = \mathbf c, \mathbf D = \mathbf d)\) method, we can switch back to the \(\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 - p_{ij}^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i)\) method to make the contrast plot. We might further extrapolate from that method to compute the average relative probabilities for the control condition with

$$\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i),$$

and average relative probabilities for the experimental condition with

$$\mathbb E_j (p_{ij}^1 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i).$$

Here’s what that can look like for our cumulative probit ANCOVA.

# conditional probabilities

p3 <- avg_predictions(fit2, newdata = nd_id, by = c("protection", "group")) %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(protection = ifelse(protection == 0, "E[italic(j)](hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^0)", "E[italic(j)](hat(italic(p))[italic(ij)]^1)")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = group, y = estimate, ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high,

color = protection)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 1:4 / 10, color = "white") +

geom_linerange(linewidth = 3/4, position = position_dodge(width = 1/3)) +

geom_point(aes(shape = protection),

position = position_dodge(width = 1/3),

size = 3) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_y_continuous("probability", limits = c(0, 0.5)) +

labs(subtitle = "Conditional probabilities",

x = expression(Likert~response~option~(italic(j)))) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(0.85, 0.9))

# contrasts

p4 <- avg_comparisons(fit2, variables = "protection") %>%

data.frame() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = group, y = estimate, ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = -2:2 / 10, color = "white") +

geom_pointrange(linewidth = 3/4, size = 1/3) +

scale_y_continuous(expression(E(italic(p[ij])^1-italic(p[ij])^0)), limits = c(-0.25, 0.25)) +

labs(subtitle = expression(Delta[italic(j)]^{ATE}~(contrasts)),

x = expression(Likert~response~option~(italic(j))))

# combine and entitle

p3 + p4 + plot_annotation(title = "Cumulative probit ANCOVA")

Across each of the \(J\) levels of our ordinal variable, the conditional probabilities and their contrasts are more precise when based on our cumulative probit ANCOVA model, fit2, with its nice baseline covariates. This is in sharp contrast to the latent potential outcomes results, which got less precise with the baseline covariates.

Response contrast wrap-up.

Boes’s conditional probabilities approach is nice in that it clearly connects the causal estimands to some of the primary parameters in the statistical model \((\mathbb p)\), and it emphasizes the ordinal nature of the dependent variable. This approach also benefits from high-quality baseline covariates. The multidimensional nature of the causal estimand \(\Delta_j^\text{ATE}\) seems mixed. On the one hand, this approach seems more sophisticated than an overall summary. On the other hand, a multidimensional estimand may make it harder to communicate the primary results to audiences not filled with stats geeks.

\(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\): Differences in ordinal items summarized as continuous.

Substantive researchers often summarize ordinal variables with means and standard deviations, much like they would with truly continuous variables. Though this practice is not statistically rigorous, many substantive researchers find this meaningful. It turns out there’s a known way to compute the “mean” of an ordinal variable using the parameters of an ordinal model, and it’s pretty simple. Say you have some ordinal variable called rating, with \(J\) response options, and \(p_j\) denoting the probability for a given option. You can compute the mean with the equation

$$\mathbb E(\text{rating}) = \sum_1^J p_j \times j,$$

which is just a formal way of saying the mean for your ordinal rating variable is the same as the sum of the \(p_j\) probabilities multiplied by their \(j\) response values. If our rating variable ranged from 1 to 4, and each of those values was equally probable, here’s how we’d compute the mean.

tibble(j = 1:4) %>%

mutate(pj = .25) %>%

mutate(`pj * j` = pj * j) %>%

summarise(mean = sum(`pj * j`))

## # A tibble: 1 × 1

## mean

## <dbl>

## 1 2.5

Run that little code block step by step to make sure you follow. Since our cumulative probit models return the full \(\mathbb p\) vector of probabilities, we can use them to compute conditional means with this approach. Not only can we compute conditional means at the group level, \(\mathbb E (y_i^1)\) and \(\mathbb E (y_i^0)\), we could also compute conditional expectations at the participant level, \(\hat y_i^1\) and \(\hat y_i^0\). Thus, we might use this method to make causal inferences with the equation

$$ \tau_y^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E (y_i^1 - y_i^0) = \mathbb E (y_i^1) - \mathbb E (y_i^0), $$

where \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\) is the average treatment effect expressed as if the ordinal variable was continuous. We can then generalize this approach to include baseline covariates with the equation

$$ \tau_y^\text{ATE} = \mathbb E (y_i^1 - y_i^0 \mid \mathbf C_i, \mathbf D_i). $$

Let’s see how this could work in practice.

\(\beta_1\) and \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\).

To my knowledge, there is no way to compute \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\) based with the \(\beta_1\) parameter alone. This method requires we use the parameters from the full ordinal model.

\(\mathbb E (y_i^1 - y_i^0)\) without and with covariates.

We will use standardization to compute \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\) via the \(\mathbb E (y_i^1 - y_i^0)\) method. For our brm() models, we can do this with fitted()- or add_epred_draws()-based workflows. However, I recommend we focus on the add_epred_draws() approach, as the fitted() approach will make for overly complex code. For this method, we start with a full predictor grid with each participants’ prez value, and counterfactual values for the independent variable protection. We’ve already saved such a grid as nd_id. Here’s another look.

# update the data grid

nd_id <- coyne2022 %>%

select(id, male, prez) %>%

expand_grid(protection = 0:1) %>%

mutate(row = 1:n())

# what?

glimpse(nd_id)

## Rows: 706

## Columns: 5

## $ id <int> 1, 1, 3, 3, 9, 9, 11, 11, 12, 12, 13, 13, 21, 21, 22, 22, 24, 24, 25, 25, 28, 28, 32, 32,…

## $ male <dbl> 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,…

## $ prez <dbl> 2.3284981, 2.3284981, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 1.4456196, 0.5627412, 0.5627412, 1…

## $ protection <int> 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1,…

## $ row <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25…

We’ve already saved the initial add_epred_draws()-based code in a previous section. We saved the ANOVA results as fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id and the ANCOVA results as fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id. Using the fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id object as a starting point, here’s how we might then use our ordinal ANOVA to compute participant-level \(\hat y_i^1\) and \(\hat y_i^0\) estimates, and their contrasts.

# conditional expectations

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

# convert the .category factor to numeric

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

# compute p[j] * j

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

# group and convert to the y_hat metric

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

# summarize

group_by(id, protection) %>%

mean_qi(y_hat) %>%

# just show the first 6 rows

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 8

## id protection y_hat .lower .upper .width .point .interval

## <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 1 0 2.20 2.05 2.35 0.95 mean qi

## 2 1 1 2.26 2.10 2.42 0.95 mean qi

## 3 3 0 2.20 2.05 2.35 0.95 mean qi

## 4 3 1 2.26 2.10 2.42 0.95 mean qi

## 5 9 0 2.20 2.05 2.35 0.95 mean qi

## 6 9 1 2.26 2.10 2.42 0.95 mean qi

# contrasts

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

# convert the .category factor to numeric

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

# compute p[j] * j

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

# group and convert to the y_hat metric

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

# convert to the wide format with respect to protection

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = y_hat) %>%

# compute the protection contrast

mutate(`1 - 0` = `1` - `0`) %>%

# group and summarize by id

group_by(id) %>%

mean_qi(`1 - 0`) %>%

# just show the first 6 rows

head()

## # A tibble: 6 × 7

## id `1 - 0` .lower .upper .width .point .interval

## <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 1 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

## 2 3 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

## 3 9 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

## 4 11 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

## 5 12 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

## 6 13 0.0578 -0.165 0.276 0.95 mean qi

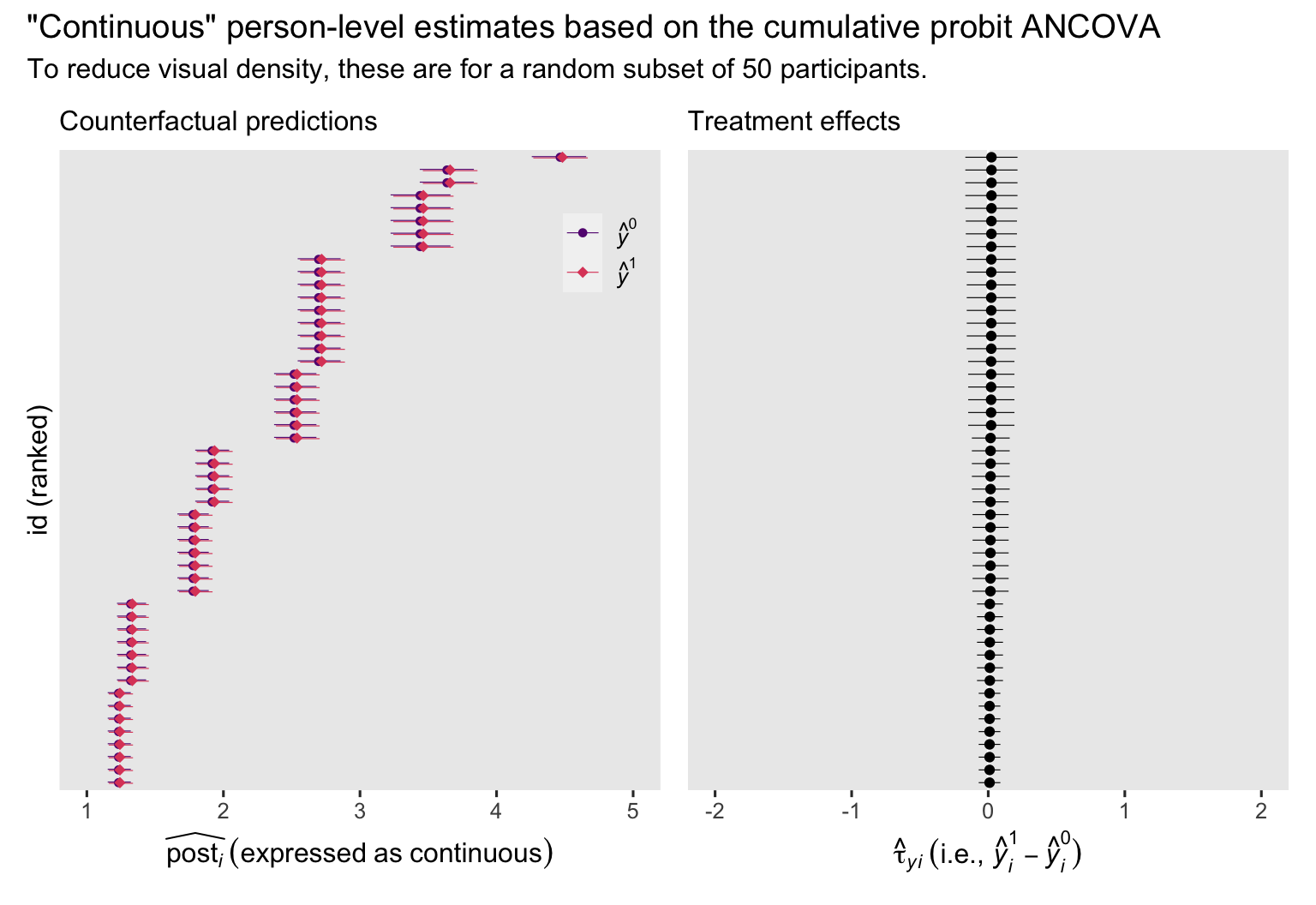

Because there are no baseline covariates in the cumulative probit ANOVA, the results are the same across all participants. Now we use the same approach, but applied to the cumulative probit ANCOVA fit2. We’ll plot the results for our \(n = 50\) subset from above.

# conditional expectations

p1 <- fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

# subset

filter(id %in% random_50) %>%

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

group_by(id, protection) %>%

mean_qi(y_hat) %>%

mutate(y = ifelse(protection == 0, "hat(italic(y))^0", "hat(italic(y))^1")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = y_hat, y = reorder(id, y_hat), color = y)) +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = .lower, xmax = .upper),

position = position_dodge(width = -0.2),

size = 1/5) +

geom_point(aes(shape = y),

size = 2) +

scale_color_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", begin = .3, end = .6,

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_shape_manual(NULL, values = c(20, 18),

labels = scales::parse_format()) +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "Counterfactual predictions",

x = expression(widehat(post[italic(i)])~(expressed~as~continuous)),

y = "id (ranked)") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(1, 5)) +

theme(legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.position = c(.9, .85))

# contrasts

p2 <- fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

# subset

filter(id %in% random_50) %>%

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = y_hat) %>%

mutate(d = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(id) %>%

mean_qi(d) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = d, y = reorder(id, d))) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = "white") +

geom_interval(aes(xmin = .lower, xmax = .upper),

position = position_dodge(width = 0.25),

size = 1/5, color = "black") +

geom_point() +

scale_y_discrete(breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "Treatment effects",

x = expression(hat(tau)[italic(yi)]~("i.e., "*hat(italic(y))[italic(i)]^1-hat(italic(y))[italic(i)]^0)),

y = NULL) +

xlim(-2, 2)

# combine and entitle

p1 + p2 +

plot_annotation(title = '"Continuous" person-level estimates based on the cumulative probit ANCOVA',

subtitle = "To reduce visual density, these are for a random subset of 50 participants.")

In the case of the cumulative probit ANCOVA, the \(y_i^1 - y_i^0\) contrasts do differ across participants, albeit not much in the case of the data from Coyne et al. (

2022).

Here’s how we might compute \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\) estimate with each model.

# ANOVA

fit1_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = y_hat) %>%

# compute the protection contrast

mutate(d = `1` - `0`) %>%

# group and summarize across levels of id

group_by(.draw) %>%

summarise(d = mean(d)) %>%

# summarize the ATE

summarise(m = mean(d),

s = sd(d),

ll = quantile(d, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(d, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## m s ll ul

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.0578 0.112 -0.165 0.276

# ANCOVA

fit2_conditional_probabilities_by_id %>%

mutate(j = as.double(.category)) %>%

mutate(product = j * .epred) %>%

group_by(id, protection, .draw) %>%

summarise(y_hat = sum(product)) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = protection, values_from = y_hat) %>%

mutate(d = `1` - `0`) %>%

group_by(.draw) %>%

summarise(d = mean(d)) %>%

summarise(m = mean(d),

s = sd(d),

ll = quantile(d, probs = .025),

ul = quantile(d, probs = .975))

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## m s ll ul

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.0172 0.0714 -0.122 0.156

The poster means for the \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\) were similar for the two models, but the posterior SD was about 40% smaller for the cumulative probit ANCOVA. Once again, baseline covaraites helped us make our causal inferences with greater precision.

\(\mathbb E (y_i^1) - \mathbb E (y_i^0)\) without and with covariates.

To use the \(\mathbb E (y_i^1) - \mathbb E (y_i^0)\) method with the cumulative probit ANOVA, we only need the simple nd predictor grid from before. Just in case you’ve forgotten, we’ll define it again. Then we’ll show the add_epred_draws()-based workflow to compute our estimates for \(\mathbb E (y_i^1)\), \(\mathbb E (y_i^1)\), and their contrast \(\tau_y^\text{ATE}\).

# we've defined this predictor grid before

nd <- tibble(protection = 0:1)

# now compute

nd %>%

add_epred_draws(fit1) %>%