Notes on the Bayesian cumulative probit

By A. Solomon Kurz

December 29, 2021

What/why?

Prompted by a couple of my research projects, I’ve been fitting a lot of ordinal models, lately. Because of its nice interpretive properties, I’m fond of using the cumulative probit. Though I’ve written about cumulative logit ( Kurz, 2020b, sec. 11.1) and probit models ( Kurz, 2020a, Chapter 23) before, I still didn’t feel grounded enough to make rational decisions about priors and parameter interpretations. In this post, I have collected my recent notes and reformatted them into something of a tutorial on the Bayesian cumulative probit model. Using a single psychometric data set, we explore a variety of models, starting with the simplest single-level thresholds-only model and ending with a conditional multilevel distributional model.

Be warned: This isn’t exactly a tutorial for beginners to the cumulative probit. For introductions, see some of the references cited within.

Set it up

All code is in R ( R Core Team, 2022), with healthy doses of the tidyverse ( Wickham et al., 2019; Wickham, 2022) for data wrangling and plotting. All models are fit with brms ( Bürkner, 2017, 2018, 2022). In addition, there are a couple places where I make good use of the tidybayes package ( Kay, 2022).

Here we load the packages and adjust the global plotting theme.

# load

library(tidyverse)

library(brms)

library(tidybayes)

# adjust the global plotting theme

theme_set(

theme_gray(base_size = 13,

base_family = "Times") +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank())

)

Our data will be a subset of the bfi data (

Revelle et al., 2010) from the

psych package (

Revelle, 2022). Here we load, subset, and wrangle the data to suit our needs.

set.seed(1)

d <- psych::bfi %>%

mutate(male = ifelse(gender == 1, 1, 0),

female = ifelse(gender == 2, 1, 0)) %>%

drop_na() %>%

slice_sample(n = 200) %>%

mutate(id = 1:n()) %>%

select(id, male, female, N1:N5) %>%

pivot_longer(N1:N5, names_to = "item", values_to = "rating")

# what is this?

glimpse(d)

## Rows: 1,000

## Columns: 5

## $ id <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7…

## $ male <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

## $ female <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

## $ item <chr> "N1", "N2", "N3", "N4", "N5", "N1", "N2", "N3", "N4", "N5", "N1", "N2", "N3", "N4", "N5", "N1", "N2", "…

## $ rating <int> 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4, 2, 5, 3, 4, 6, 2, 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 4, 4, 1, 2, 1, 2, 4, 4, 1…

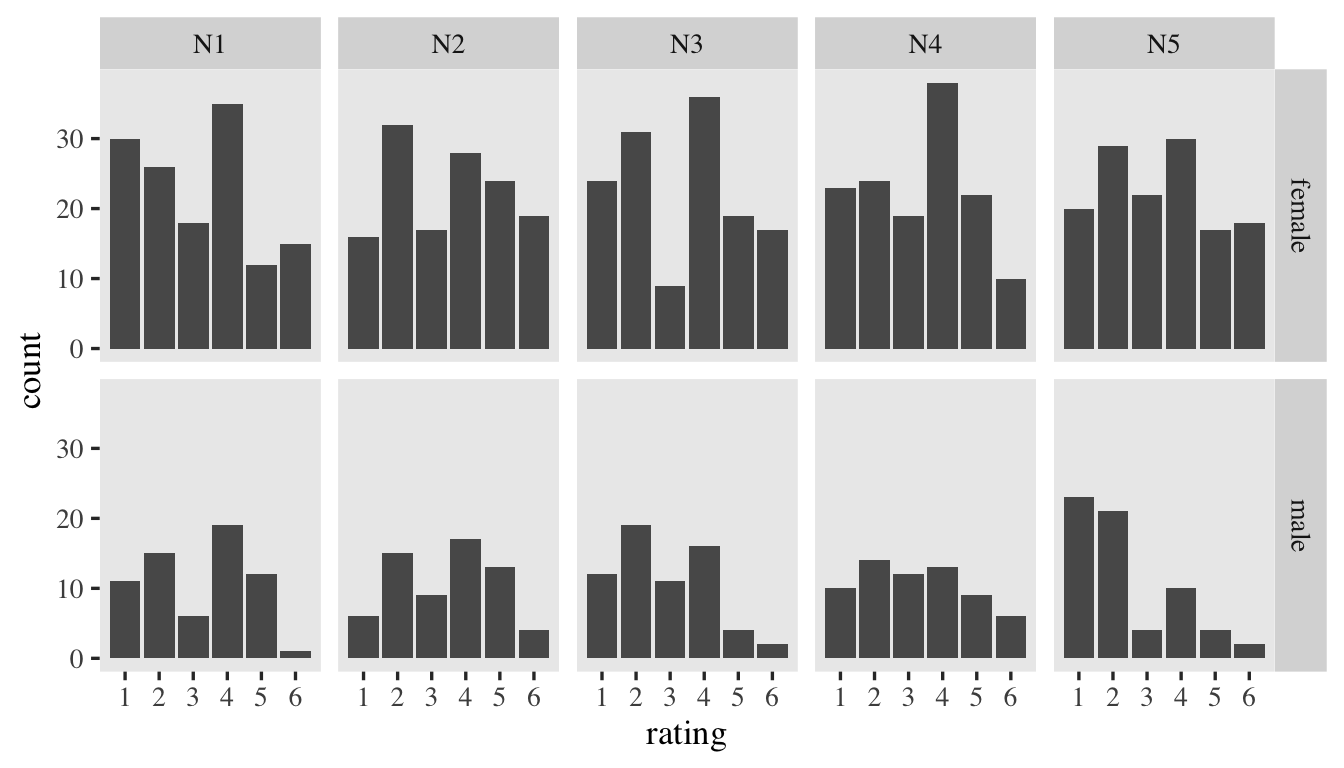

Our focal variables will be rating, which is a combination of the responses to the five questions in the Neuroticism scale of a version of the Big Five inventory (

Goldberg, 1999). Here’s a quick plot of the responses, by item and sex.

d %>%

mutate(sex = ifelse(male == 0, "female", "male")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = rating)) +

geom_bar() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:6) +

facet_grid(sex ~ item)

Basics of the ordered probit

I’ve had a difficult time understanding the notation used in these models. As McElreath ( 2015, p. 335) remarked, there are a lot of different notational approaches for describing these models. In this post, I’ll be using a blend of sensibilities from McElreath, Bürkner ( 2020), and Kruschke ( 2015). If you see flaws in my equations, do drop me a comment.

Given a Likert-type variable rating for which there are \(K + 1 = 6\) response options, you can model the relative probability of each ordinal category as

$$p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) = f(\tau_k) - f(\tau_{k - 1}),$$

where \(\tau_k\) is the \(k^\text{th}\) threshold. On the left side of the equation, we stated the relative probabilities of the ordinal categories is conditional on our set of thresholds \(\{ \tau_k \}\), which is a shorthand for writing out \(\{k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4, k_5\}\). The \(f(\cdot)\) operator is a stand-in for some cumulative distribution function, which will allow us to map the cumulative probabilities onto an unbounded parameter space divided up by the \(K\) thresholds.

Because of its nice interpretative properties, I (and many others) like to use the cumulative standard normal distribution \(\Phi\) as our function \(f(\cdot)\), which means we can rewrite the equation as

$$p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) = \Phi(\tau_k) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1}),$$

where, to be explicit, the parameters for \(\Phi\) are fixed to \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma = 1\) for purposes of identification. However, if you wanted two write out the equation to explicitly include our fixed \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) parameters, it could look like

$$p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) = \Phi([\tau_k - \mu] / \sigma) - \Phi([\tau_{k - 1} - \mu] / \sigma).$$

But again, since those are both held constant as \(0\) and \(1\), respectively, substituting those values into the equation reduces to what it was, before. This is one of the nice things about starting off with the cumulative standard normal distribution.

Anyway, the thing to understand is that the area under the normal curve to the left of \(\tau_k\) is defined as \(\Phi(\tau_k)\), which is the cumulative probability mass for the \(k^\text{th}\) rating. The reason we have to subtract the area to the left of \(\Phi(\tau_{k - 1})\) from \(\Phi(\tau_k)\) is so we can isolate a relative probability from a cumulative probability. This applies in the same way for all the middle ratings–2 through 5 in our case. For the first and last ratings (1 and 6), we might add two virtual thresholds \(-\infty\) and \(\infty\), respectively. With the first rating, this means

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) & = \Phi(\tau_1) - \Phi({\color{blue}{\tau_0}}) \\ & = \Phi(\tau_1) - \Phi({\color{blue}{-\infty}} ) \\ & = \Phi(\tau_1) - \color{blue}0 \\ & = \Phi(\tau_1). \end{align*}

$$

In a similar way, for the last rating we have

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) & = \Phi({\color{blue}{\tau_{K + 1}}} ) - \Phi(\tau_K) \\ & = \Phi({\color{blue}\infty} ) - \Phi(\tau_K) \\ & = {\color{blue}1} - \Phi(\tau_K). \end{align*}

$$

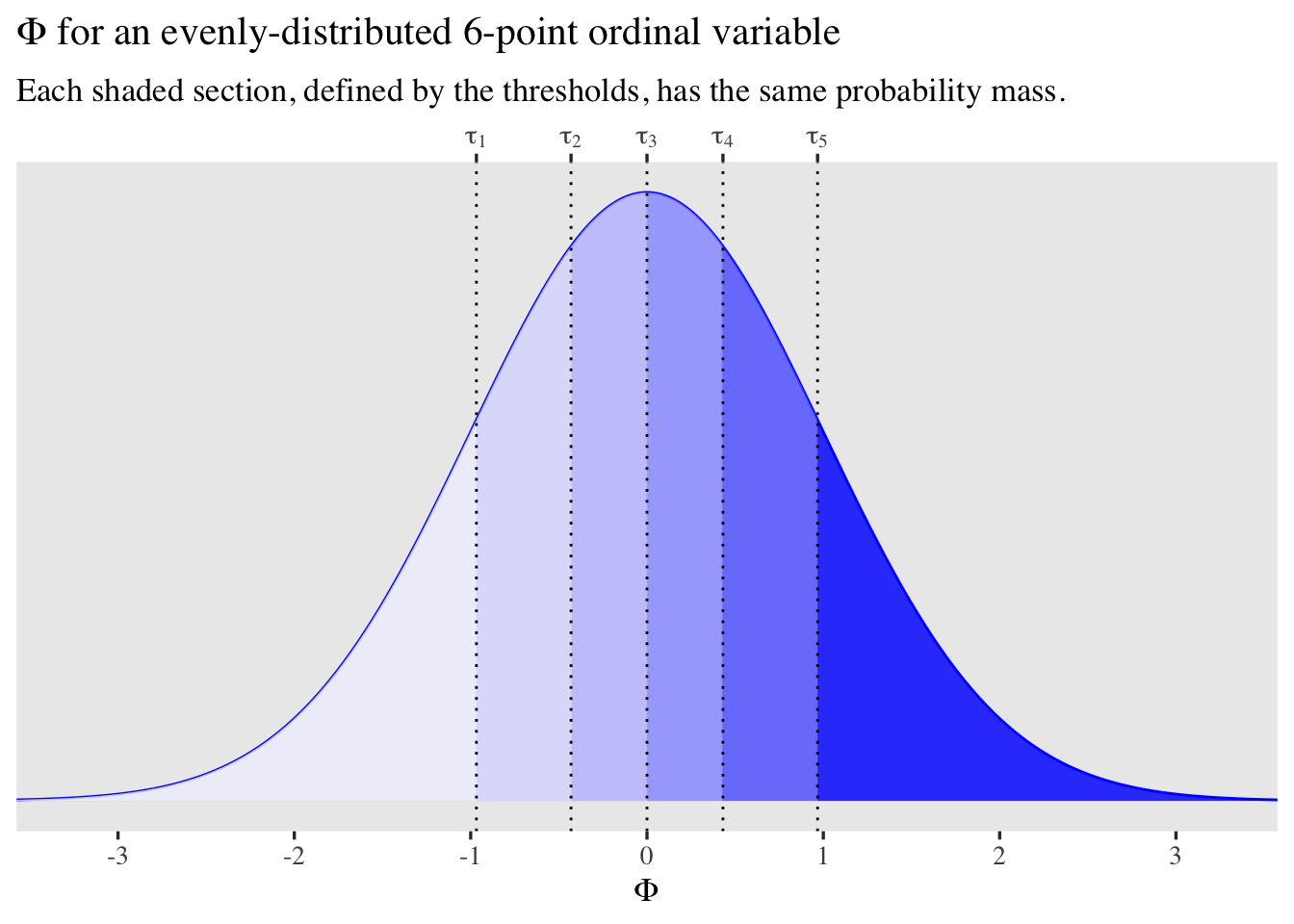

It might help to visualize this. Consider a case where we have a rating variable with 6 values (1 through 6), each with equal proportions, \(1 / 6 \approx .167.\) Here’s what that could look like mapped onto \(\Phi\).

tibble(z = seq(from = -3.75, to = 3.75, length.out = 1e3)) %>%

mutate(d = dnorm(x = z, mean = 0, sd = 1)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = z, y = d)) +

geom_line(color = "blue") +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 0 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 1 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 2 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 3 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 4 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_area(aes(fill = z >= qnorm(p = 5 / 6)), alpha = 1/4) +

geom_vline(xintercept = qnorm(p = 1:5 / 6), linetype = 3) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("transparent", "blue"), breaks = NULL) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(Phi), breaks = -3:3,

sec.axis = dup_axis(

name = NULL,

breaks = qnorm(p = 1:5 / 6),

labels = parse(text = str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"))

)) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-3.25, 3.25)) +

labs(title = expression(Phi*" for an evenly-distributed 6-point ordinal variable"),

subtitle = "Each shaded section, defined by the thresholds, has the same probability mass.")

Here’s how you might compute some of those values within a tibble.

tibble(rating = 1:6) %>%

mutate(proportion = 1/6) %>%

mutate(cumulative_proportion = cumsum(proportion)) %>%

mutate(right_hand_threshold = qnorm(cumulative_proportion))

## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## rating proportion cumulative_proportion right_hand_threshold

## <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 0.167 0.167 -0.967

## 2 2 0.167 0.333 -0.431

## 3 3 0.167 0.5 0

## 4 4 0.167 0.667 0.431

## 5 5 0.167 0.833 0.967

## 6 6 0.167 1 Inf

Alternatively, here’s how to use qnorm() within pnorm() to realize the various combinations of \(\Phi(\tau_k) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1})\).

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 1 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 0 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 2 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 1 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 3 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 2 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 4 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 3 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 5 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 4 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 6 / 6)) - pnorm(q = qnorm(p = 5 / 6))

## [1] 0.1666667

Models

For practice and building intuition, we’ll be fitting 8 models to the Neuroticism items. Starting simple and building up, they will be:

fit1, the thresholds-only model;fit2, the single-level conditional mean model;fit3, the single-level conditional mean and dispersion model;fit4, the multilevel random participant-means model;fit5, the multilevel random participant- and item-level means model;fit6, the multilevel random participant- and item-level means model with varying thresholds;fit7, the multilevel unconditional distributional model; andfit8, the multilevel conditional distributional model.

I make no claim these titles are canonical. They just make sense to me.

Thresholds only.

Over the years, I’ve become fond of McElreath’s style of writing out models. His style usually looks something like

$$

\begin{align*} \text{criterion}_i & \sim \operatorname{Some likelihood}(\phi_i) \\ \text{some link function}(\phi_i) & = \alpha + \beta x_i \\ \alpha & \sim \text{< some prior >} \\ \beta & \sim \text{< some prior >}, \end{align*}

$$

where \(\phi_i\) is a stand-in for the likelihood parameter(s). I’ve had a hard time applying this notation style to the cumulative probit model, so I’m going to detract a bit. Here’s my current attempt applied to the thresholds-only model:

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) & = \Phi(\tau_k) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1}) \\ \tau_k & \sim \mathcal N(0, 2), \end{align*}

$$

where the first line is the likelihood, which only contains the model parameters \(\tau_k\). The second line is a simple non-committal prior for the thresholds, which places \(95\%\) of the prior probability mass for each threshold between \(-4\) and \(4\). However, if we consider the plot above, we can come up with default prior that are a little less lazy. If we want our starting assumption to be a uniform distribution between our rating data, we could update the model to

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}) & = \Phi(\tau_k) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1}) \\ \tau_1 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_5 & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1), \end{align*}

$$

where the priors are now all sequentially centered in different places in the \(\Phi\) space. Though it might initially seem bold to use \(1\) for the standard deviations on each, that’s still rather permissive when you consider the figure, above. I think you could easily justify using a \(0.5\) or so, instead.

Here’s how to fit the model with brms.

fit1 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

rating ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2

)

You don’t necessarily have to adjust init_r, but my experience is these models often benefit from this adjustment.

Here’s the model summary.

print(fit1)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: rating ~ 1

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -0.94 0.05 -1.03 -0.85 1.00 3334 2650

## Intercept[2] -0.25 0.04 -0.33 -0.17 1.00 5251 3510

## Intercept[3] 0.07 0.04 -0.00 0.15 1.00 4869 3513

## Intercept[4] 0.74 0.04 0.66 0.83 1.00 5449 3979

## Intercept[5] 1.32 0.05 1.21 1.43 1.00 5336 3509

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

As Bürkner explained in his (

2020) tutorial, the Intercept[k] rows are actually summarizing the \(\tau_k\) thresholds, not the \(\mu\) intercept for the underlying latent variable. That, recall, is fixed at \(0\) for identification purposes. Also, notice that the disc parameter is similarly held constant at \(1\) for identification.

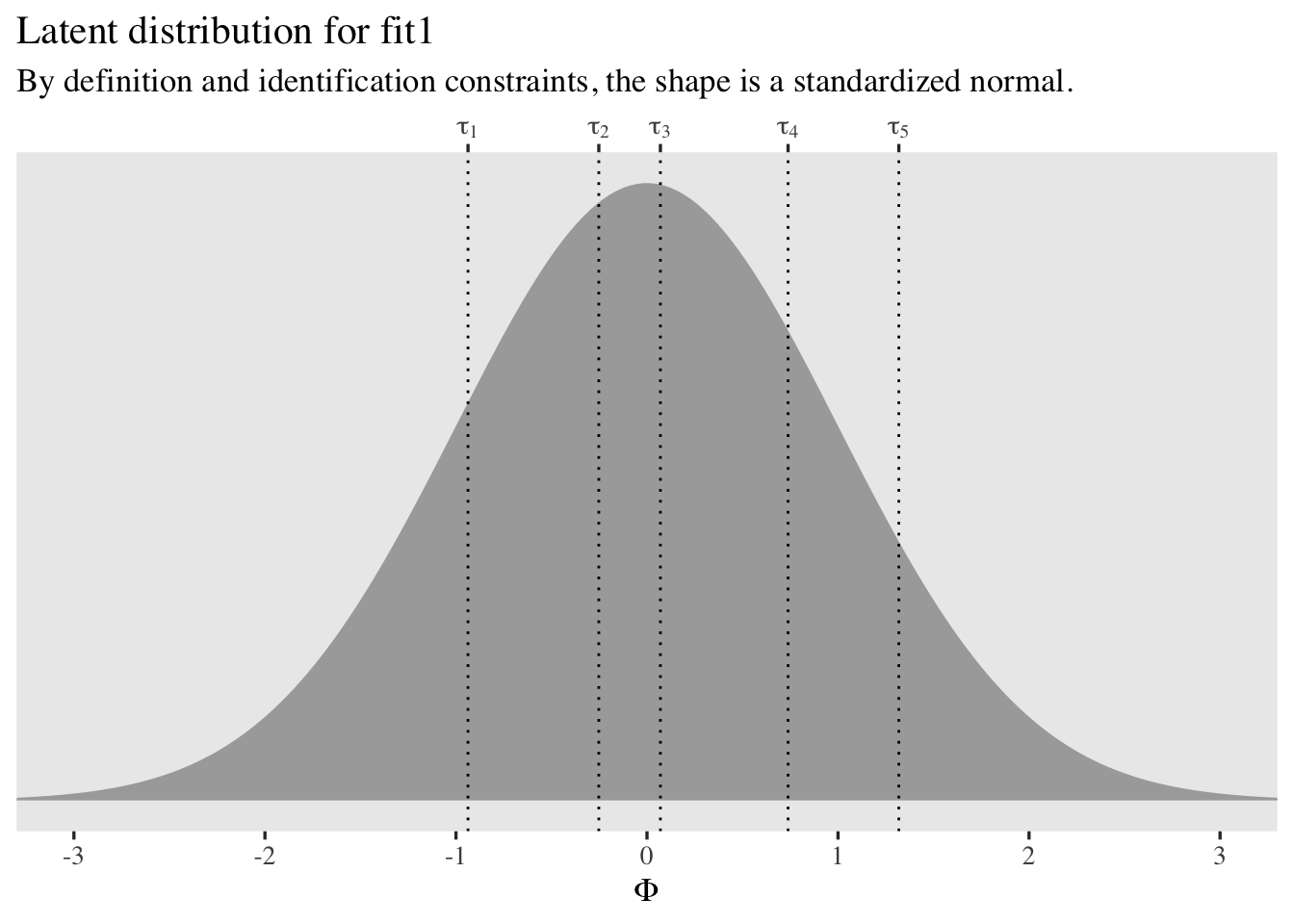

It might help to visualize the thresholds in a plot.

tibble(x = seq(from = -3.5, to = 3.5, length.out = 200)) %>%

mutate(d = dnorm(x = x)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = "black", alpha = 1/3) +

geom_vline(xintercept = fixef(fit1)[, 1], linetype = 3) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(Phi), breaks = -3:3,

sec.axis = dup_axis(

name = NULL,

breaks = fixef(fit1)[, 1] %>% as.double(),

labels = parse(text = str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"))

)) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-3, 3)) +

labs(title = "Latent distribution for fit1",

subtitle = "By definition and identification constraints, the shape is a standardized normal.")

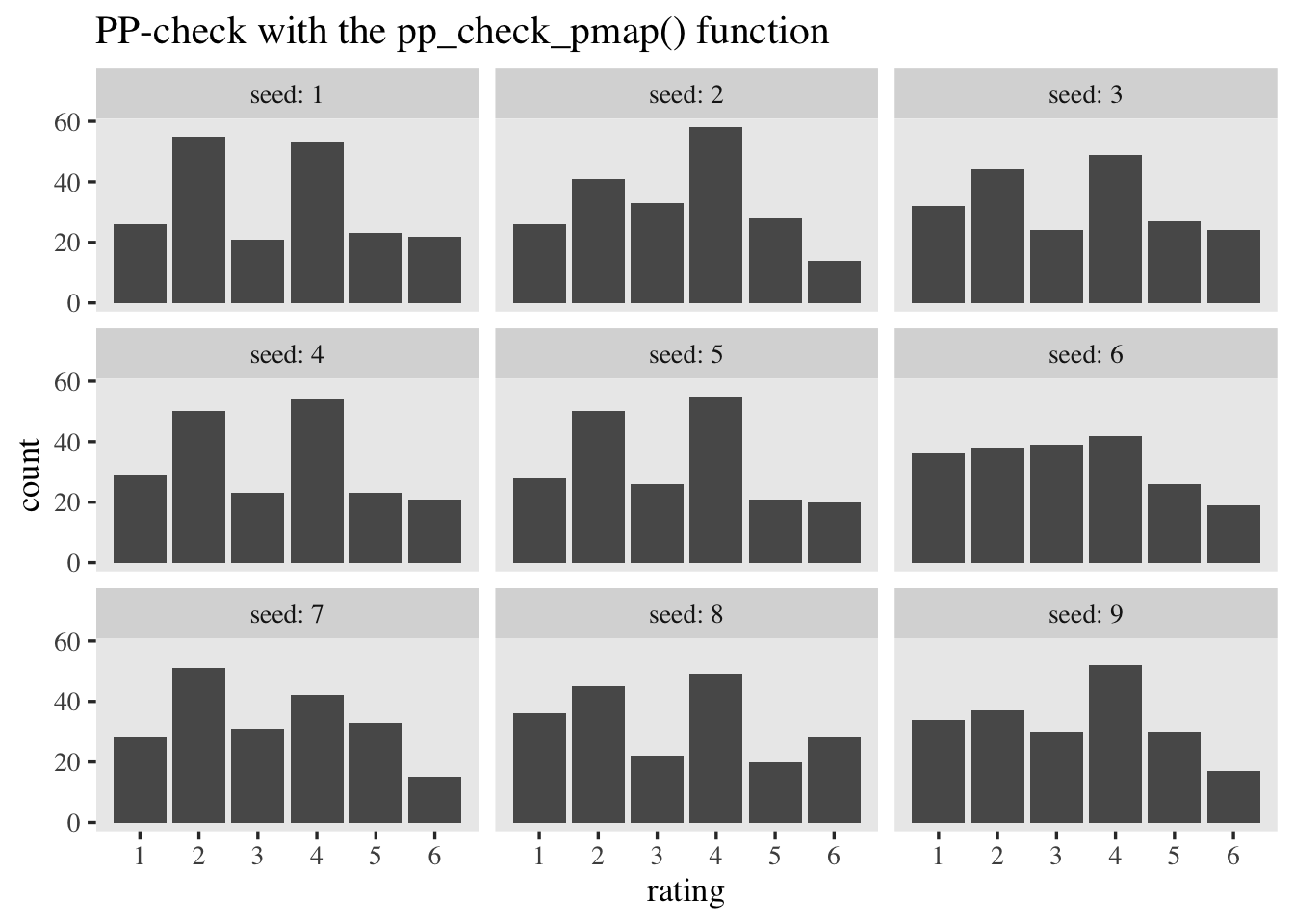

To get more practice working with the thresholds and how they relate to the actual rating data, it’ll help to to a couple posterior-predictive checks by hand. For our first version, we’ll make a custom function called pp_check_pmap(), which will make use of the pmap_dbl() function.

pp_check_pmap <- function(seed = 0) {

set.seed(seed)

as_draws_df(fit1) %>%

slice_sample(n = 200) %>%

select(starts_with("b_Intercept")) %>%

set_names(str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]")) %>%

mutate(p1 = pnorm(`tau[1]`),

p2 = pnorm(`tau[2]`) - pnorm(`tau[1]`),

p3 = pnorm(`tau[3]`) - pnorm(`tau[2]`),

p4 = pnorm(`tau[4]`) - pnorm(`tau[3]`),

p5 = pnorm(`tau[5]`) - pnorm(`tau[4]`),

p6 = 1 - pnorm(`tau[5]`)) %>%

mutate(rating = pmap_dbl(.l = list(p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6),

.f = ~sample(

x = 1:6,

size = 1,

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(..1, ..2, ..3, ..4, ..5, ..6)

))) %>%

select(rating)

}

Now use pp_check_pmap() to simulate \(9\) data sets resembling the original data.

tibble(seed = 1:9) %>%

mutate(sim = map(seed, pp_check_pmap)) %>%

unnest(sim) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = rating)) +

geom_bar() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:6) +

ggtitle("PP-check with the pp_check_pmap() function") +

facet_wrap(~ seed, labeller = label_both)

We can gain more insights into the model by using a different approach to computing the rating probabilities. This time, we’ll use an approach that leverages the case_when() function. We’ll wrap the approach in a custom function called pp_check_case_when().

pp_check_case_when <- function(seed = 0) {

set.seed(seed)

as_draws_df(fit1) %>%

slice_sample(n = 200) %>%

select(starts_with("b_Intercept")) %>%

set_names(str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]")) %>%

mutate(Phi = rnorm(n = n(), mean = 0, sd = 1)) %>%

mutate(rating = case_when(

Phi < `tau[1]` ~ 1,

Phi >= `tau[1]` & Phi < `tau[2]`~ 2,

Phi >= `tau[2]` & Phi < `tau[3]`~ 3,

Phi >= `tau[3]` & Phi < `tau[4]`~ 4,

Phi >= `tau[4]` & Phi < `tau[5]`~ 5,

Phi >= `tau[5]` ~ 6

)) %>%

select(rating)

}

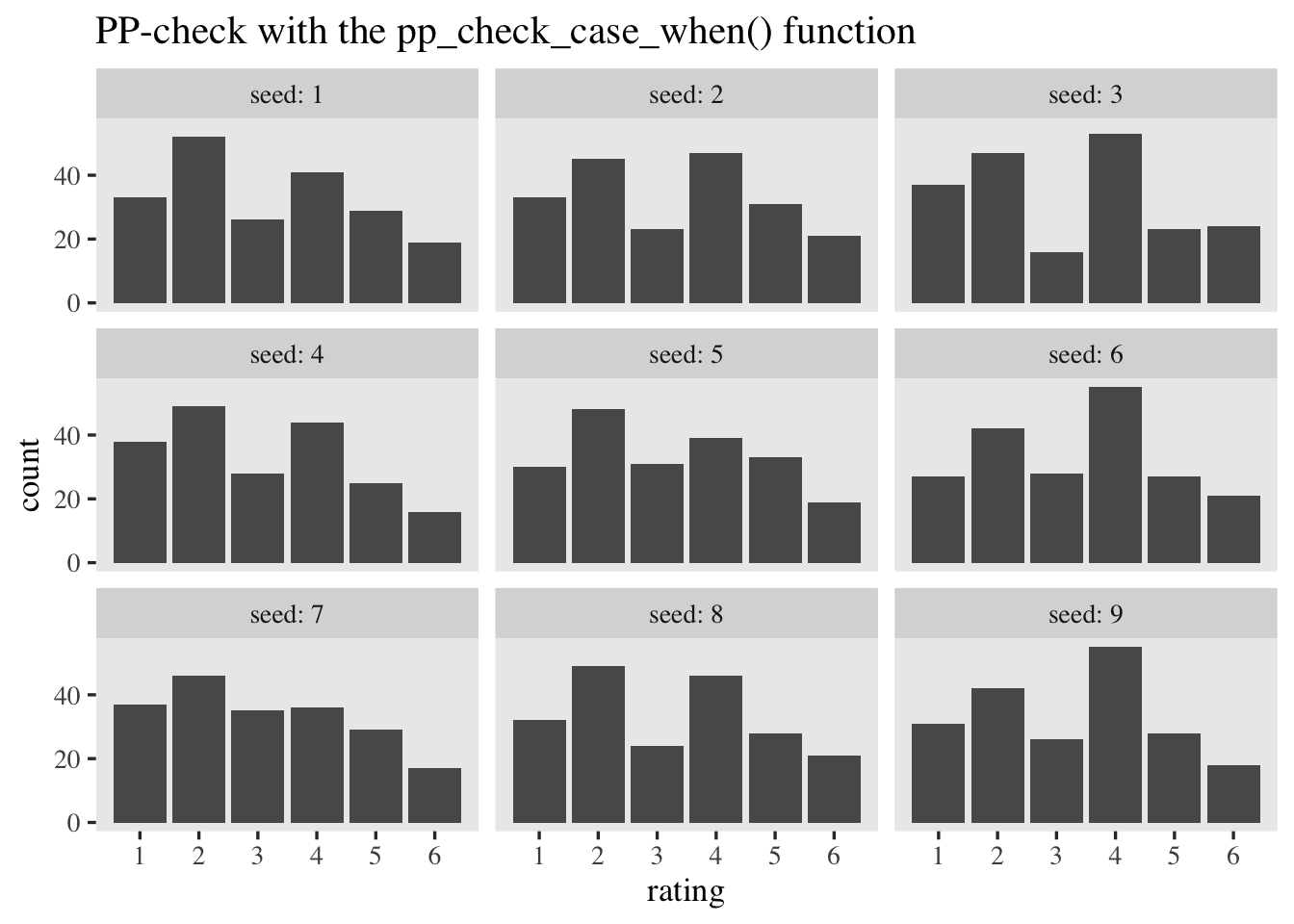

Now use pp_check_pmap() to simulate \(9\) data sets resembling the original data.

tibble(seed = 1:9) %>%

mutate(sim = map(seed, pp_check_case_when)) %>%

unnest(sim) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = rating)) +

geom_bar() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:6) +

ggtitle("PP-check with the pp_check_case_when() function") +

facet_wrap(~ seed, labeller = label_both)

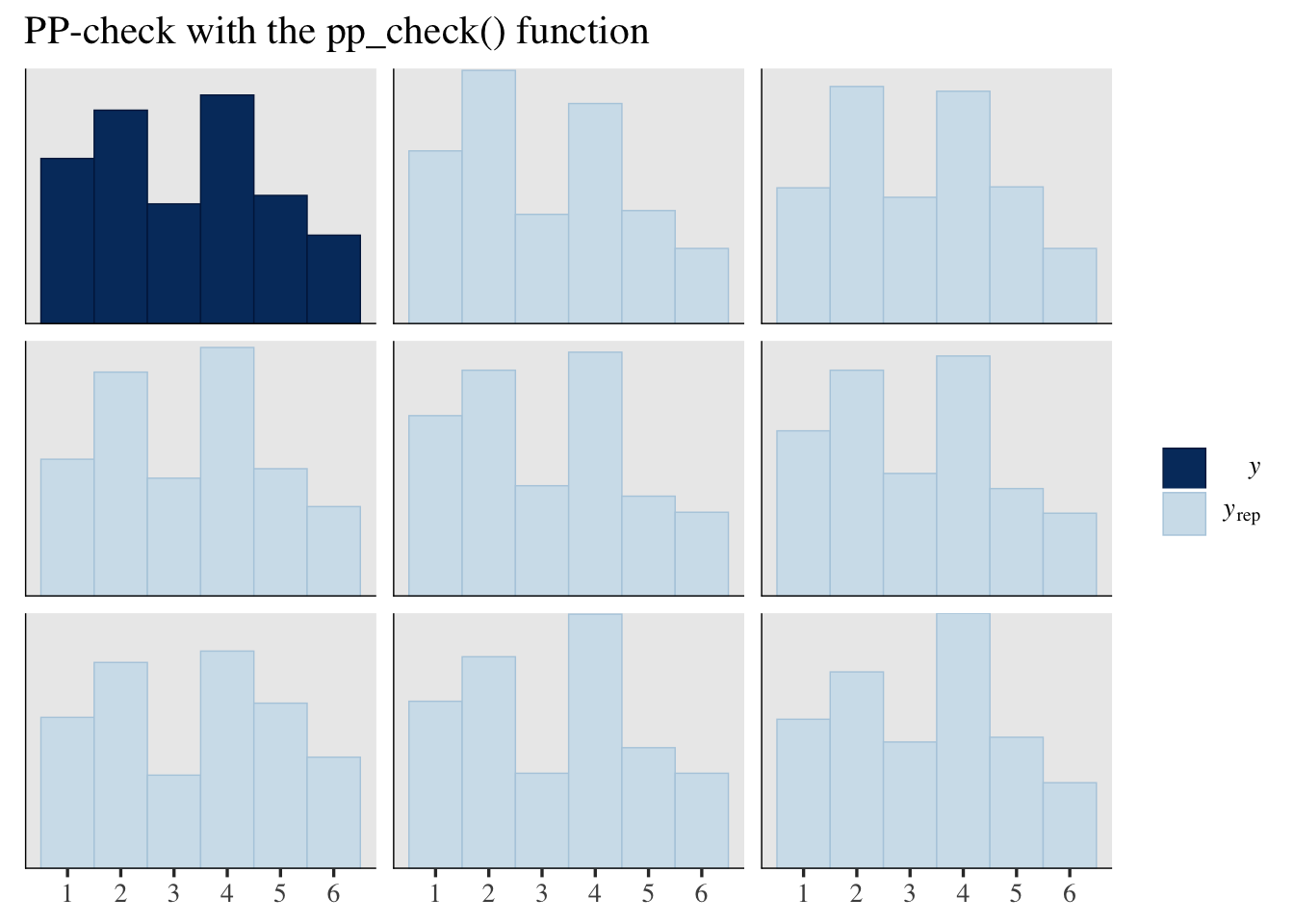

Both hand-done pp-checks returned similar results from those you can get with the pp_check() function.

pp_check(fit1, type = "hist", ndraws = 8, binwidth = 1) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:6) +

ggtitle("PP-check with the pp_check() function")

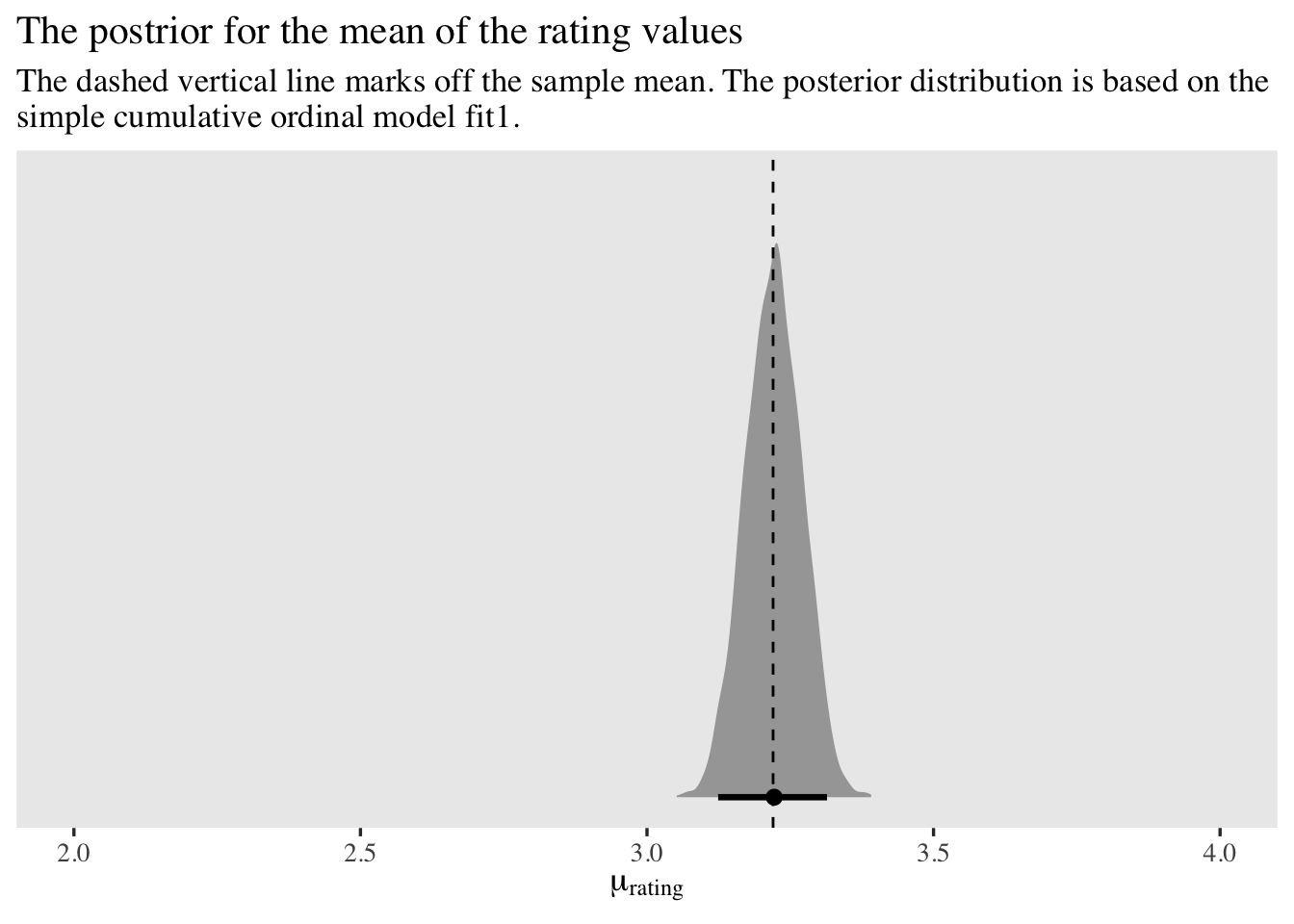

Posterior predictive distributions are cool and all, but one of the most common sense questions a researcher would ask is How do I use the model to compute the mean of the data? When you have an ordinal model, the mean of the criterion variable is the sum of the \(p_k\) probabilities multiplied by the \(k\) values of the criterion. We might express this in an equation as

$$ \mathbb{E}(\text{rating}) = \sum_1^K p_k \times k, $$

where \(\mathbb{E}\) is the expectation operator (the model-based mean), \(p_k\) is the probability of the \(k^\text{th}\) ordinal value, and \(k\) is the actual ordinal value. The trick, here, is that because we are computing all the \(p_k\) values with MCMC and expressing those values as posterior distributions, we have to perform this operation within each of our MCMC draws. If we take cues from our pp_check_pmap(), above, we can compute this with our posterior draws like so.

as_draws_df(fit1) %>%

select(.draw, starts_with("b_Intercept")) %>%

set_names(".draw", str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]")) %>%

# compute the p_k distributions

mutate(p1 = pnorm(`tau[1]`),

p2 = pnorm(`tau[2]`) - pnorm(`tau[1]`),

p3 = pnorm(`tau[3]`) - pnorm(`tau[2]`),

p4 = pnorm(`tau[4]`) - pnorm(`tau[3]`),

p5 = pnorm(`tau[5]`) - pnorm(`tau[4]`),

p6 = 1 - pnorm(`tau[5]`)) %>%

# wrangle

pivot_longer(starts_with("p"), values_to = "p") %>%

mutate(rating = str_extract(name, "\\d") %>% as.double()) %>%

# compute p_k * k

mutate(`p * rating` = p * rating) %>%

# sum those values within each posterior draw

group_by(.draw) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = sum(`p * rating`)) %>%

# plot!

ggplot(aes(x = mean_rating, y = 0)) +

stat_halfeye(.width = .95) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(d$rating), linetype = 2) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "The postrior for the mean of the rating values",

subtitle = "The dashed vertical line marks off the sample mean. The posterior distribution is based on the\nsimple cumulative ordinal model fit1.",

x = expression(mu[rating])) +

xlim(2, 4)

Our model did a great job finding the mean of the rating data.

Add a predictor.

If we would like to add a predictor, the most natural way is probably to explicitly add \(\mu\) in the likelihood and then attach a linear model to \(\mu_i\). This would look like

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, {\color{blue}{\mu_i}} ) & = \Phi(\tau_k {\color{blue}{- \mu_i}} ) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1} {\color{blue}{- \mu_i}} ) \\ {\color{blue}{\mu_i}} & = {\color{blue}{\beta_0 + \sum_1^l \beta_l x_l}} \\ {\color{blue}{\beta_0}} & = {\color{blue}0} , \end{align*}

$$

where \(\beta_0\) is the intercept for the latent mean and \(\sum_1^l \beta_l x_l\) is the additive effect of the full set of \(l\) predictor variables and their \(\beta_l\) coefficients. Now \(\beta_0\) is the parameter we set to zero for identification purposes. As before, the \(\sigma\) parameter will remain set to \(1\).

Since we are modeling a latent mean with a latent standard deviation of \(1\), this puts

- single continuous standardized predictors in a correlation metric and

- single dummy variables in a Cohen’s-$d$ metric.

As soon as you have multiple predictor variables in the mix, their metrics become increasingly difficult to interpret, but at least you can surmise that a partial correlation or a conditional Cohen’s \(d\) isn’t on a radically different metric from their univariable counterparts.

In the case of these data, our predictor of interest will be the dummy variable male. Thus, it makes sense to assign it a weakly-regularizing prior like \(\mathcal N(0, 1)\). Here’s the model formula:

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_i) & = \Phi(\tau_k - \mu_i) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_i) \\ \mu_i & = \beta_1 \text{male}_i \\ \tau_1 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_5 & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \beta_1 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1), \end{align*}

$$

where now the reference category is female. Here’s how to fit the model with brms.

# 49.33003 secs

fit2 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

rating ~ 1 + male,

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5),

prior(normal(0, 1), class = b)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2

)

Check the summary.

print(fit2)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: rating ~ 1 + male

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -1.02 0.05 -1.12 -0.91 1.00 3167 3036

## Intercept[2] -0.33 0.05 -0.42 -0.24 1.00 4809 3628

## Intercept[3] -0.00 0.05 -0.09 0.09 1.00 4785 3571

## Intercept[4] 0.67 0.05 0.57 0.77 1.00 5309 3523

## Intercept[5] 1.25 0.06 1.13 1.37 1.00 5651 3799

## male -0.22 0.07 -0.36 -0.09 1.00 5139 3154

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

Since the \(\beta_1\) coefficient is a mean difference on the latent-$\Phi$ scale, it might be instructive to compare it to a Cohen’s \(d\) computed with the sample statistics. Here we compute the sample means, standard deviations, and sample sizes, by male.

# sample means

m_female <- d %>% filter(female == 1) %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

m_male <- d %>% filter(male == 1) %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

# sample standard deviations

s_female <- d %>% filter(female == 1) %>% summarise(s = sd(rating)) %>% pull()

s_male <- d %>% filter(male == 1) %>% summarise(s = sd(rating)) %>% pull()

# sample sizes

n_female <- d %>% filter(female == 1) %>% summarise(n = n()) %>% pull()

n_male <- d %>% filter(male == 1) %>% summarise(n = n()) %>% pull()

Now compute the pooled standard deviation.

s_pooled <- sqrt(((n_female - 1) * s_female^2 + (n_male - 1) * s_male^2) / (n_female + n_male - 2))

We’re finally ready to compute the sample Cohen’s \(d\).

(m_male - m_female) / s_pooled

## [1] -0.2167152

Compare that with the posterior mean and 95% CIs for our \(b_1\) parameter.

fixef(fit2)["male", -2]

## Estimate Q2.5 Q97.5

## -0.22406785 -0.35812222 -0.08881928

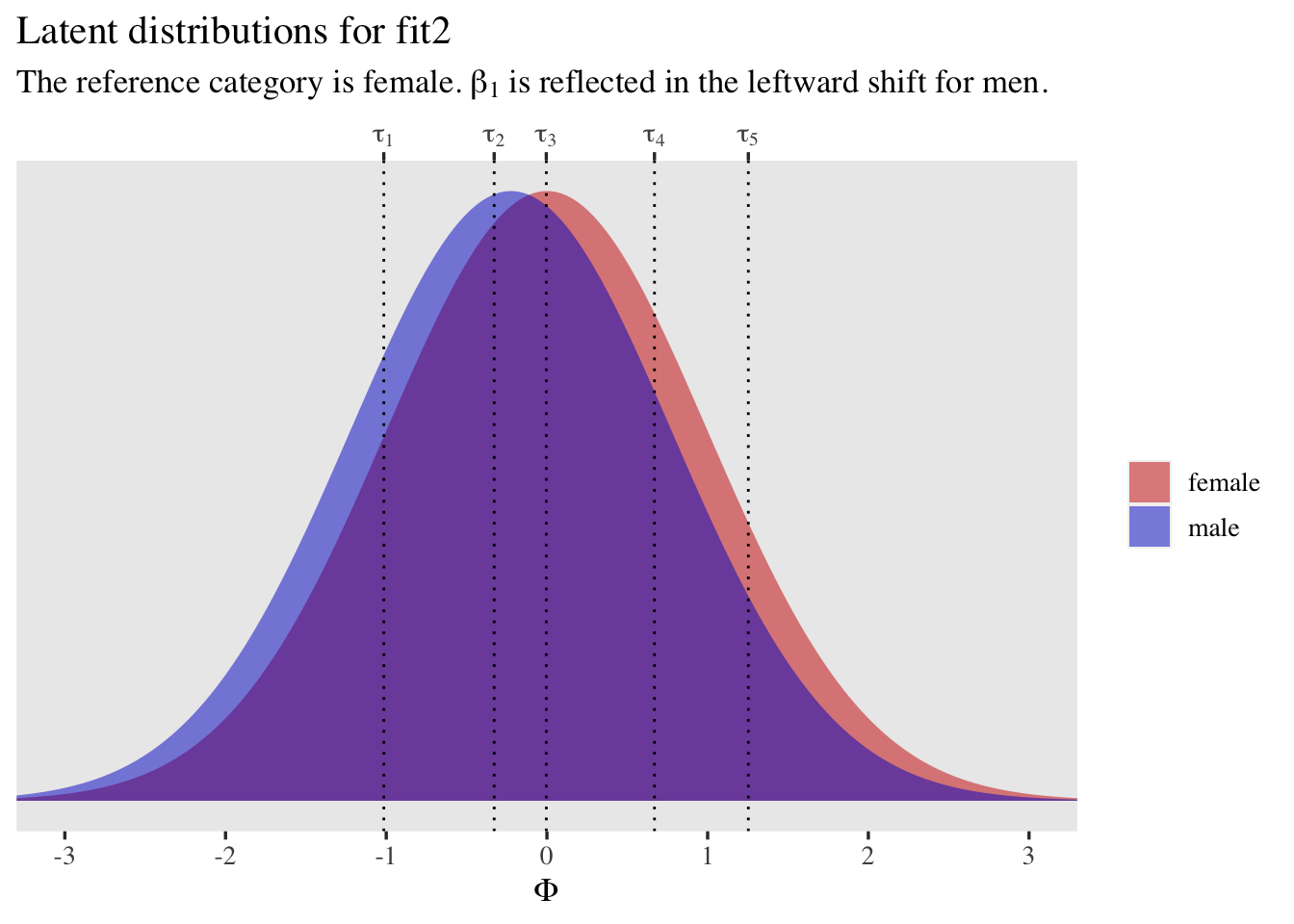

As with the first model, it might also be helpful to plot the latent distributions along with the thresholds.

tibble(male = 0:1,

mu = c(0, fixef(fit2)["male", 1])) %>%

expand(nesting(male, mu),

x = seq(from = -3.5, to = 3.5, length.out = 200)) %>%

mutate(d = dnorm(x, mean = mu, sd = 1),

sex = ifelse(male == 0, "female", "male")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d, fill = sex)) +

geom_area(alpha = 1/2, position = "identity") +

geom_vline(xintercept = fixef(fit2)[1:5, 1], linetype = 3) +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values = c("red3", "blue3")) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(Phi), breaks = -3:3,

sec.axis = dup_axis(

name = NULL,

breaks = fixef(fit2)[1:5, 1] %>% as.double(),

labels = parse(text = str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"))

)) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-3, 3)) +

labs(title = "Latent distributions for fit2",

subtitle = expression("The reference category is female. "*beta[1]*" is reflected in the leftward shift for men."))

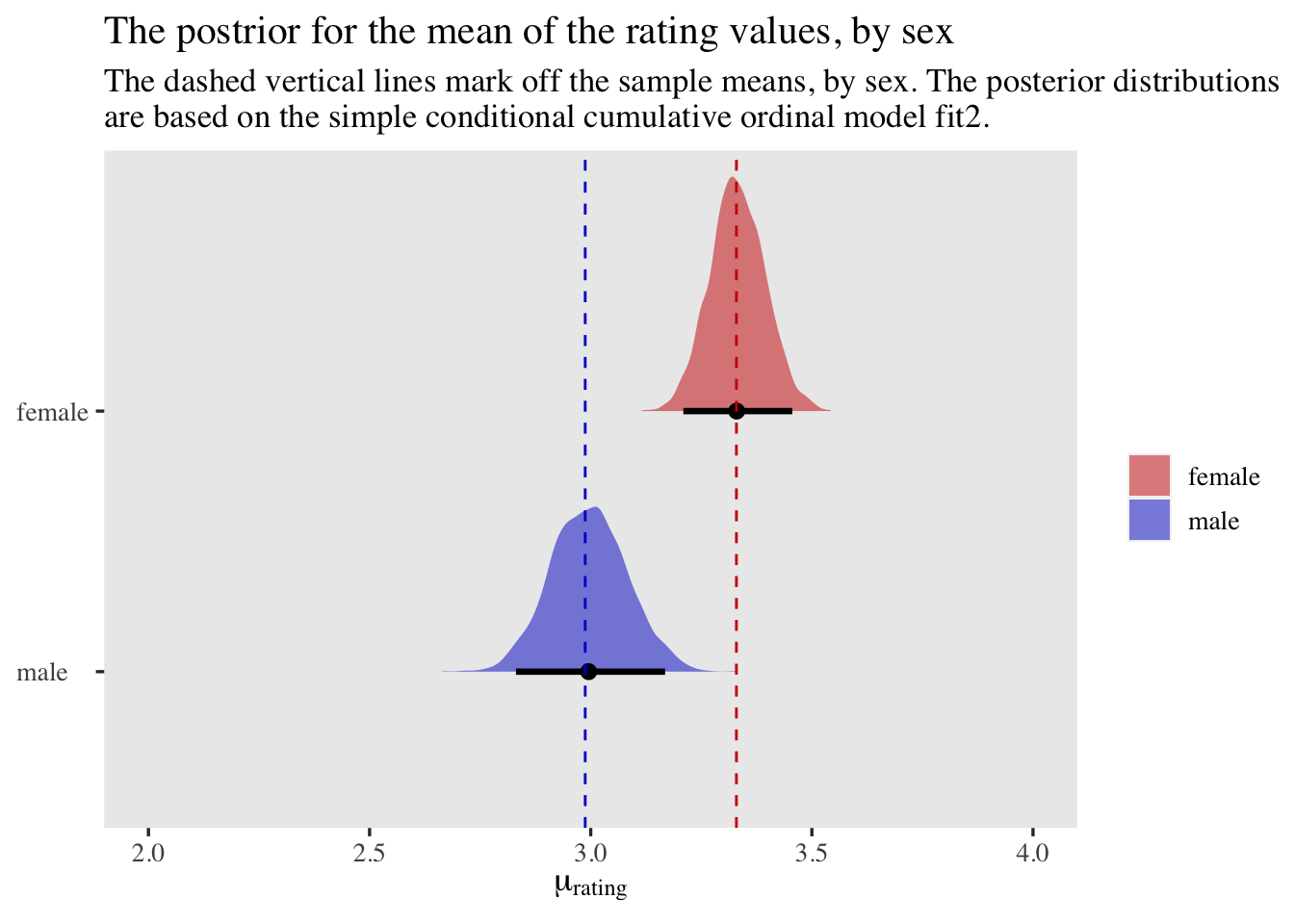

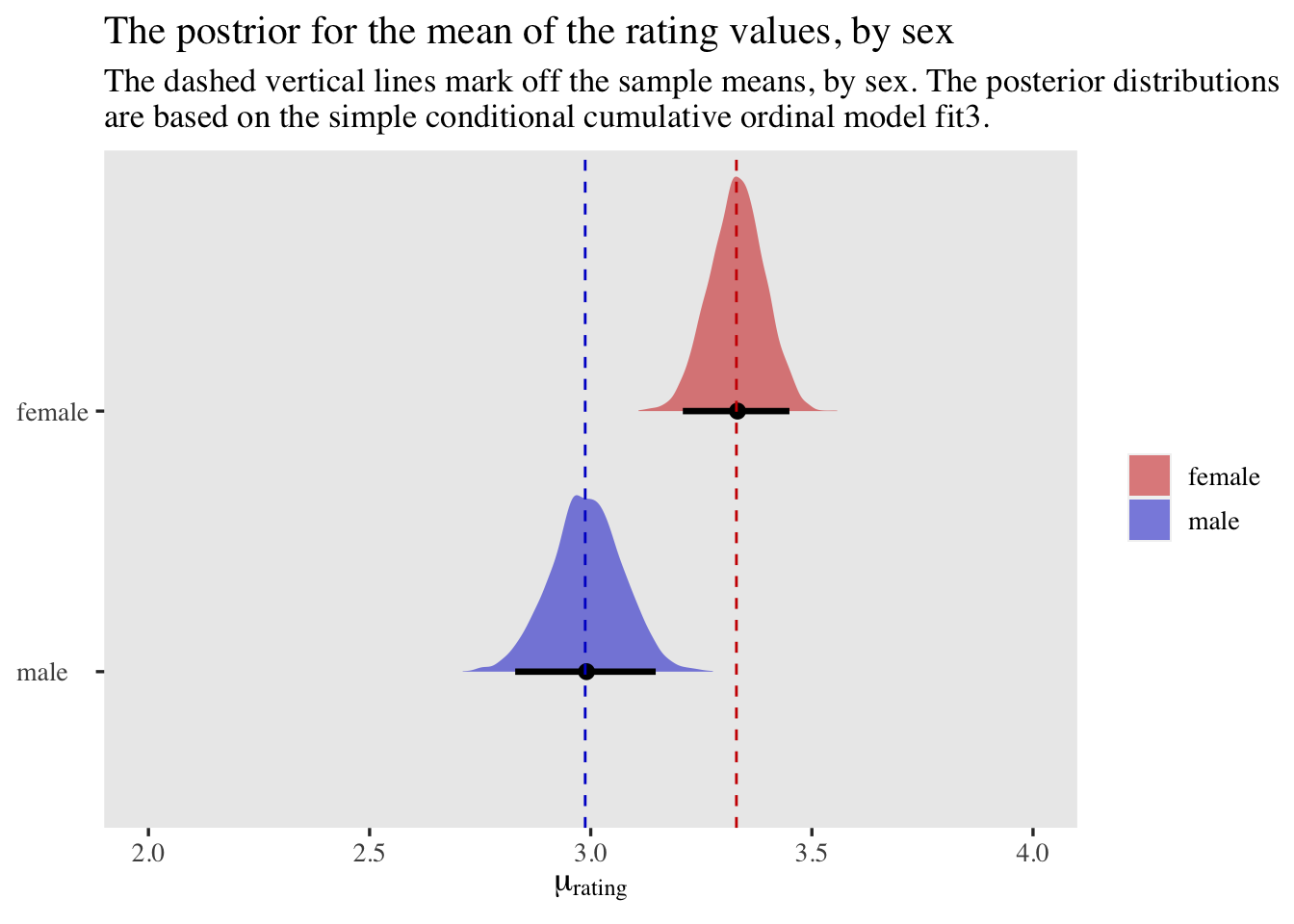

As before, we might also want to use our conditional fit2 to compute the population means for rating, by sex. We can extend our workflow from before by including the posterior draws for \(\beta_1\). Then when we use the pnorm() functions to compute the conditional probabilities, we’ll have to use \(\beta_1\) to adjust the values in the mean argument within pnorm() to account for the \(\mu_i = \beta_1 \text{male}_i\) portion of our statistical model.

as_draws_df(fit2) %>%

select(.draw, starts_with("b_")) %>%

set_names(".draw", str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"), "beta[1]") %>%

# insert another copy of the data below

bind_rows(., .) %>%

# add the two values for the dummy variable male

mutate(male = rep(0:1, each = n() / 2)) %>%

# compute the p_k values conditional on the male dummy

mutate(p1 = pnorm(`tau[1]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`),

p2 = pnorm(`tau[2]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`) - pnorm(`tau[1]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`),

p3 = pnorm(`tau[3]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`) - pnorm(`tau[2]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`),

p4 = pnorm(`tau[4]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`) - pnorm(`tau[3]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`),

p5 = pnorm(`tau[5]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`) - pnorm(`tau[4]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`),

p6 = 1 - pnorm(`tau[5]`, mean = 0 + male * `beta[1]`)) %>%

# wrangle

pivot_longer(starts_with("p"), values_to = "p") %>%

mutate(rating = str_extract(name, "\\d") %>% as.double()) %>%

# compute p_k * k

mutate(`p * rating` = p * rating) %>%

# sum those values within each posterior draw, by the male dummy

group_by(.draw, male) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = sum(`p * rating`)) %>%

mutate(sex = ifelse(male == 0, "female", "male")) %>%

# the trick with and without fct_rev() helps order the axes, colors, and legend labels

ggplot(aes(x = mean_rating, y = fct_rev(sex), fill = sex)) +

stat_halfeye(.width = .95) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_male, linetype = 2, color = "blue3") +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_female, linetype = 2, color = "red3") +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values = c(alpha("red3", 0.5), alpha("blue3", 0.5))) +

labs(title = "The postrior for the mean of the rating values, by sex",

subtitle = "The dashed vertical lines mark off the sample means, by sex. The posterior distributions\nare based on the simple conditional cumulative ordinal model fit2.",

x = expression(mu[rating]),

y = NULL) +

xlim(2, 4) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0))

By making the mean arguments within pnorm() conditional on our dummy male, we used our fit2 model to compute posteriors around the means of rating with great success.

Varying dispersion.

If we have reason to presume differences in latent standard deviations, we can explicitly add \(\sigma\) in the likelihood and then attach a linear model to \(\log(\sigma_i)\). As in other contexts, it’s generally a good idea to model \(\log(\sigma_i)\) instead of \(\sigma_i\) because the former will ensure the model will only predict positive values. This would look like

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_i, {\color{blue}{\sigma_i}} ) & = \Phi([\tau_k - \mu_i] {\color{blue}{/ \sigma_i}} ) - \Phi([\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_i] {\color{blue}{/ \sigma_i}} ) \\ \mu_i & = \beta_0 + \sum_1^l \beta_l x_l \\ {\color{blue}{\log(\sigma_i)}} & = {\color{blue}{\eta_0 + \sum_1^m \eta_m x_m}} \\ \beta_0 & = 0 \\ {\color{blue}{\eta_0}} & = {\color{blue}0} , \end{align*}

$$

where \(\eta_0\) is the intercept for the logged latent standard deviation and \(\sum_1^m \eta_m x_m\) is the additive effect of the full set of \(m\) predictor variables and their \(\eta_m\) coefficients. Now \(\eta_0\) is set to zero for identification purposes. Recall that \(\exp(0) = 1\), which means that the default is still that \(\sigma_i = 1\) when all predictors are set to zero. With this model, it is possible the \(l\) and \(m\) predictor sets are the same. Here we differentiate between them just to make clear that they can differ, as needed.

A technical thing to keep in mind is that brms actually parameterizes cumulative probit models in terms of the discrimination parameter \(\alpha\), rather than \(\sigma\). Their relation is simple in that the one is the reciprocal of the other,

$$

\begin{align*} \sigma & = \frac{1}{\alpha}, \text{and} \\ \alpha & = \frac{1}{\sigma}. \end{align*}

$$

It’s also the case that when you fit a model without a linear model attached to the discrimination parameter,

$$ \sigma = \frac{1}{\alpha} = \frac{1}{1} = 1. $$

However, things become more complicated when you want to model \(\alpha\). First, here’s the updated likelihood:

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_i, {\color{blue}{\alpha_i}} ) & = \Phi({\color{blue}{\alpha_i}} [\tau_k - \mu_i]) - \Phi( {\color{blue}{\alpha_i}} [\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_i]) \\ \mu_i & = \beta_0 + \sum_1^l \beta_l x_l \\ {\color{blue}{\log(\alpha_i)}} & = {\color{blue}{\eta_0 + \sum_1^m \eta_m x_m}} \\ \beta_0 & = 0 \\ \eta_0 & = 0. \end{align*}

$$

If you want to convert \(\log(\alpha_i)\) to the \(\sigma\) metric, you need the transformation

$$ \sigma = \frac{1}{\exp(\log \alpha)}, $$

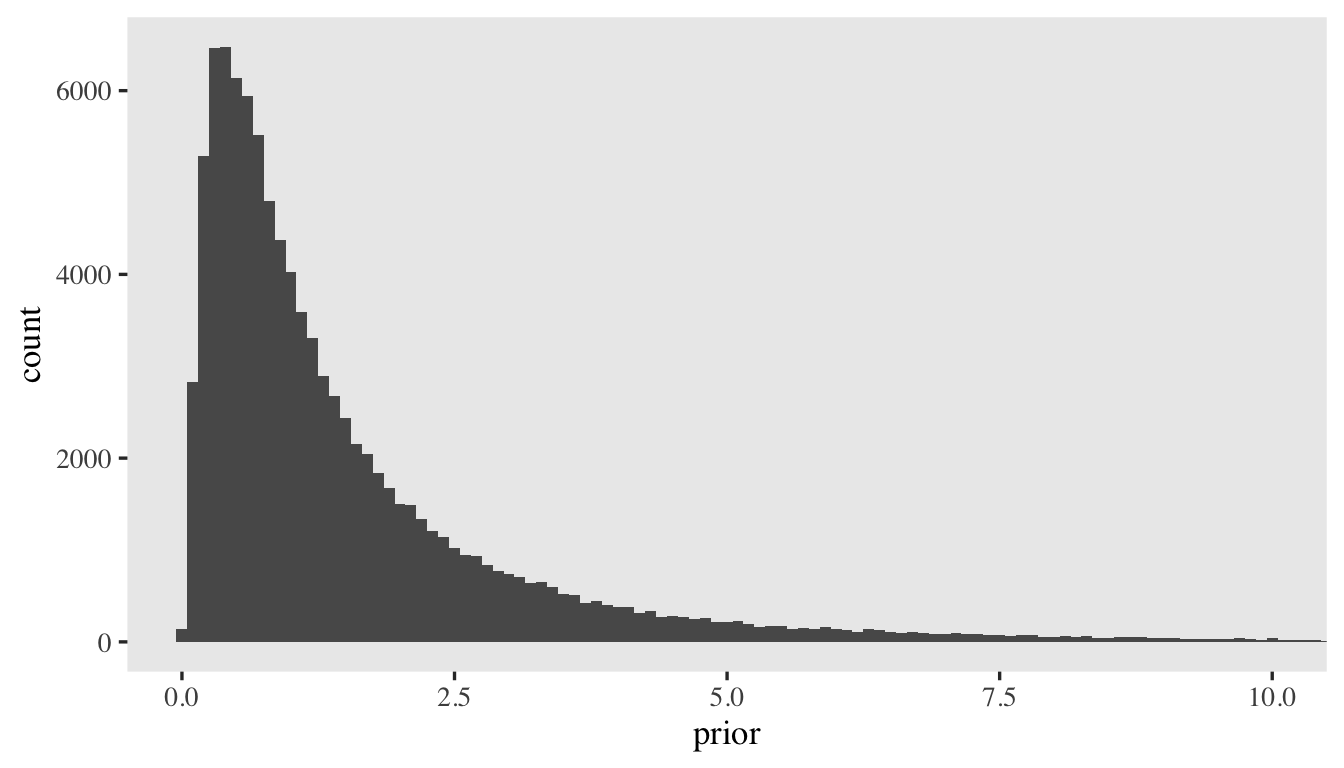

which puts the priors on the linear model for \(\log(\alpha_i)\) on an unfamiliar metric. As is often the case, something like \(\mathcal N(0, 1)\) is a good starting point. Here’s what it would look like if we simulated \(100{,}000\) draws from that prior and then converted them to the \(1 / \exp(\cdot)\) metric.

set.seed(1)

tibble(prior = rnorm(n = 1e5, mean = 0, sd = 1)) %>%

mutate(prior = 1 / exp(prior)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = prior)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.1) +

# the right tail is very long

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 10))

We might extend this approach further to consider zero-centered normal priors with different values for the \(\sigma\) hyperparameter.

set.seed(1)

tibble(sigma_hyperparameter = 1:10 / 10) %>%

mutate(x = map(sigma_hyperparameter, ~ rnorm(n = 1e5, sd = .x))) %>%

unnest(x) %>%

mutate(x = 1 / exp(x)) %>%

group_by(sigma_hyperparameter) %>%

summarise(m = mean(x),

mdn = median(x),

s = sd(x),

q2.5 = quantile(x, prob = .025),

q97.5 = quantile(x, prob = .975)) %>%

mutate_all(round, digits = 2)

## # A tibble: 10 × 6

## sigma_hyperparameter m mdn s q2.5 q97.5

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.1 1.01 1 0.1 0.82 1.22

## 2 0.2 1.02 1 0.21 0.67 1.48

## 3 0.3 1.05 1 0.32 0.56 1.8

## 4 0.4 1.08 1 0.45 0.46 2.19

## 5 0.5 1.13 1 0.6 0.38 2.66

## 6 0.6 1.2 1 0.78 0.31 3.24

## 7 0.7 1.28 1 1 0.25 3.93

## 8 0.8 1.38 1 1.33 0.21 4.82

## 9 0.9 1.5 1 1.72 0.17 5.85

## 10 1 1.64 1 2.12 0.14 7.03

The median is always at \(1\), with varying levels of dispersion. But this doesn’t seem principled. It might be better to think in terms of how much change would be reasonable to see on \(\sigma\). In the present example, our sole predictor variable will be the dummy variable male. I’m not sure how much more or less variation we’d expect to see between the sexes on the Neuroticism ratings, but I’d be shocked if the standard deviation for one was more than twice the size of the other. Thus, since the reference category will be set to \(\sigma = 1\), we want a distribution where the bulk of the prior mass is set to half and twice that value.

sigma <- c(0.5, 1, 2)

Now convert those to \(\alpha\) values.

alpha <- 1 / sigma

Then, take the log of the \(\alpha\) values.

log(alpha)

## [1] 0.6931472 0.0000000 -0.6931472

If \(\sigma_\text{men}\) were half the size of \(\sigma_\text{women}\), we’d expect \(\eta_1 = 0.693\). Similarly, if \(\sigma_\text{men}\) were twice the size of \(\sigma_\text{women}\), we’d expect \(\eta_1 = -0.693\). Thus the prior \(\eta_i \sim \mathcal N(0, 0.693 / 2 \approx 0.347)\) would put \(95 \%\) of the prior mass within the desired range.

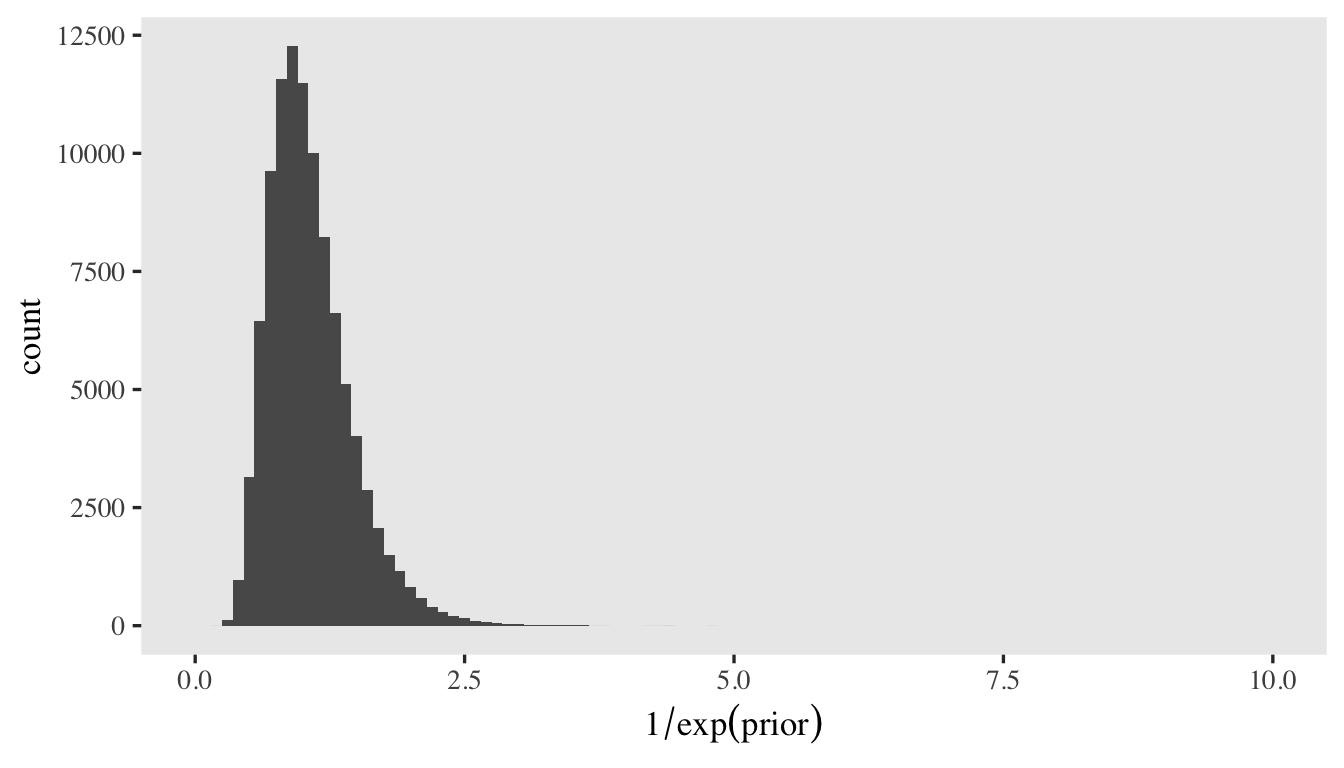

We can compute that value with \(\log(2) / 2\), too.

log(2) / 2

## [1] 0.3465736

Here’s a histogram of what that would look like in the \(1 / \exp(\cdot)\) metric.

set.seed(1)

tibble(prior = rnorm(n = 1e5, mean = 0, sd = log(2) / 2)) %>%

mutate(prior = 1 / exp(prior)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = prior)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.1) +

xlab(expression(1/exp(prior))) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 10))

With that all in mind, we can now update our model formula to:

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_i, \alpha_i) & = \Phi(\alpha_i[\tau_k - \mu_i]) - \Phi(\alpha_i[\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_i]) \\ \mu_i & = \beta_1 \text{male}_i \\ \log(\alpha_i) & = \eta_1 \text{male}_i\\ \tau_1 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_5 & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \beta_1 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \eta_1 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 0.347). \end{align*}

$$

Here’s how to fit the model with brms.

# 49.94408 secs

fit3 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

bf(rating ~ 1 + male) +

lf(disc ~ 0 + male,

# this is really important

cmc = FALSE),

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5),

prior(normal(0, 1), class = b),

# log(2) / 2 = 0.347

prior(normal(0, log(2) / 2), class = b, dpar = disc)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2

)

Note how we used the 0 + ... syntax in the first line in the lf() function and that set we set cmc = FALSE in the second line. As Bürkner noted in his (

2020) tutorial, it’s critical that you do this when attaching a model to \(\log(\alpha_i)\). If you leave these bits out, you might find that you are no longer keeping the reference category for \(\log(\alpha_i)\) set to \(0\), which can wreak havoc on the model.

Anyway, check the summary.

print(fit3)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = log

## Formula: rating ~ 1 + male

## disc ~ 0 + male

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -0.97 0.06 -1.08 -0.86 1.00 2359 2981

## Intercept[2] -0.31 0.05 -0.41 -0.22 1.00 4558 3583

## Intercept[3] -0.00 0.05 -0.09 0.09 1.00 5101 3616

## Intercept[4] 0.65 0.05 0.55 0.74 1.00 4746 3483

## Intercept[5] 1.22 0.06 1.10 1.33 1.00 4543 3337

## male -0.20 0.07 -0.34 -0.08 1.00 4535 2831

## disc_male 0.12 0.06 0.00 0.24 1.00 2799 2612

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

It can be challenging to interpret the disc_male coefficient directly. Keep in mind that larger values mean smaller relative values on the \(\sigma\) scale. Given how the reference value is \(0\), which equivalent to \(\sigma = 1\), this is the estimate of the latent standard deviation for men.

1 / exp(0 + fixef(fit3)["disc_male", -2])

## Estimate Q2.5 Q97.5

## 0.8873625 0.9976675 0.7883039

Here are the two sample standard deviations.

s_female

## [1] 1.616471

s_male

## [1] 1.491827

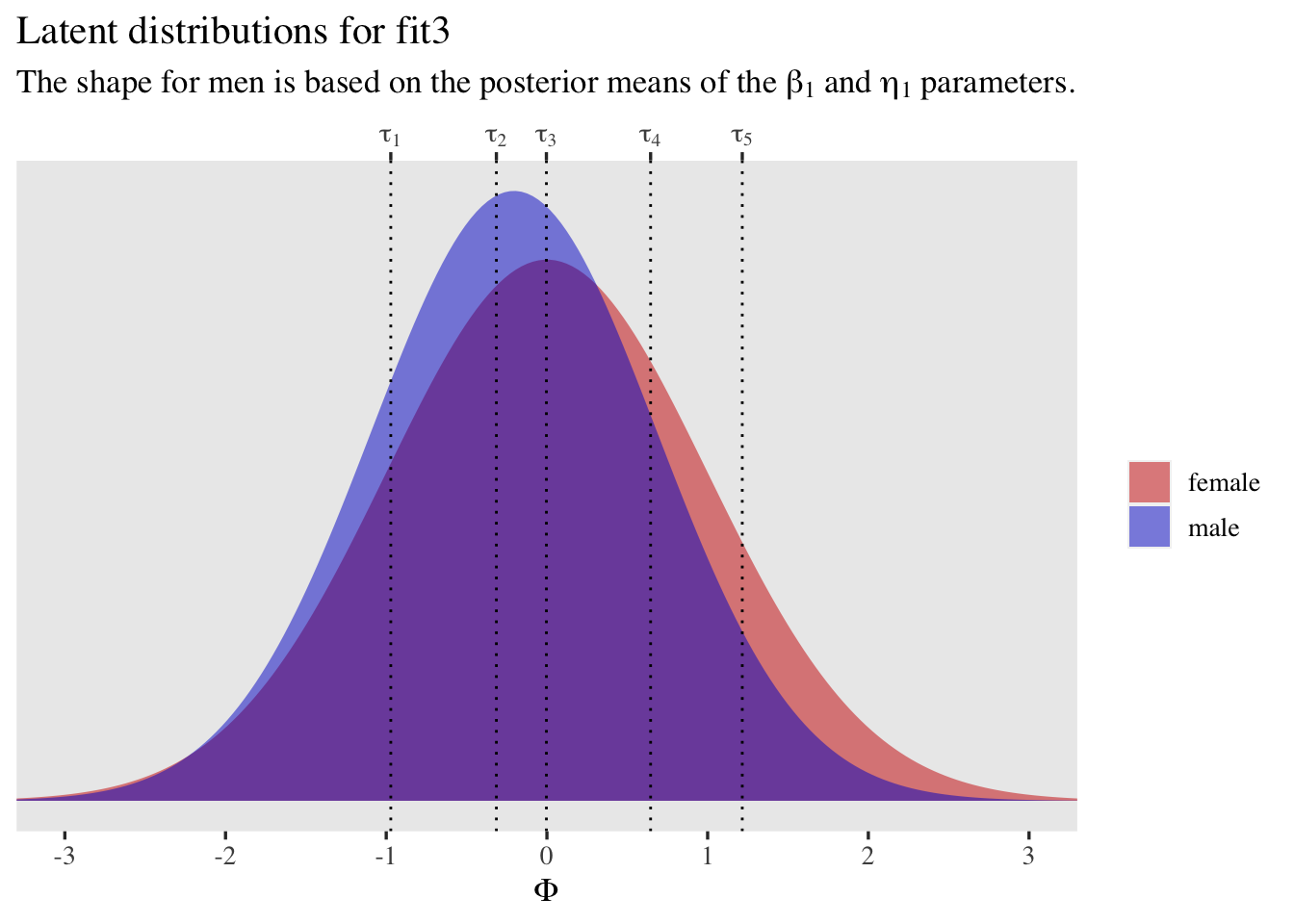

Once again, let’s plot.

tibble(male = 0:1,

mu = c(0, fixef(fit3)["male", 1]),

sigma = 1 / exp(c(0, fixef(fit3)["disc_male", 1]))) %>%

expand(nesting(male, mu, sigma),

x = seq(from = -3.5, to = 3.5, length.out = 200)) %>%

mutate(d = dnorm(x, mean = mu, sd = sigma),

sex = ifelse(male == 0, "female", "male")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d, fill = sex)) +

geom_area(alpha = 1/2, position = "identity") +

geom_vline(xintercept = fixef(fit3)[1:5, 1], linetype = 3) +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values = c("red3", "blue3")) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(Phi), breaks = -3:3,

sec.axis = dup_axis(

name = NULL,

breaks = fixef(fit3)[1:5, 1] %>% as.double(),

labels = parse(text = str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"))

)) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "Latent distributions for fit3",

subtitle = expression("The shape for men is based on the posterior means of the "*beta[1]*" and "*eta[1]*" parameters.")) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-3, 3))

Note, however, that because this new model fit3 now has separate \(\sigma\) estimates by sex, the \(\beta_1\) parameter isn’t quite in a standardized-mean-difference metric, anymore. To get it back in to a \(d\) metric, we’ll have to use the full posterior distribution for \(\sigma_\text{female}\) and \(\sigma_\text{male}\) to compute a model-based pooled standard deviation, by which we can then standardize the \(\beta_1\) coefficient.

as_draws_df(fit3) %>%

mutate(sigma_f = 1,

sigma_m = 1 / exp(b_disc_male)) %>%

mutate(sigma_pooled = sqrt(((n_female - 1) * sigma_f^2 + (n_male - 1) * sigma_m^2) / (n_female + n_male - 2))) %>%

transmute(d = b_male / sigma_pooled) %>%

mean_qi(d) %>%

mutate_if(is.double, round, digits = 3)

## # A tibble: 1 × 6

## d .lower .upper .width .point .interval

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 -0.212 -0.345 -0.08 0.95 mean qi

Also, consider the variance metric. Given that the standard deviation squared is the variance, \(\sigma^2\), an increase of doubling the standard deviation is the same as quadrupling the variance.

2^2

## [1] 4

If you wanted to set up the model so that \(95\%\) of the prior probability allowed for a doubling of the variance, you’d need to set the upper range to the square root of \(2\).

sqrt(2)

## [1] 1.414214

Anyway, now that we’ve updated the model to account for differences in \(\sigma\), we might also want to update our workflow for computing the population means for rating. The trick is now the sd argument within the pnorm() function should be conditional on the values for males or females. Here’s one way how.

as_draws_df(fit3) %>%

# this also includes the column for b_disc_male

select(.draw, starts_with("b_")) %>%

set_names(".draw", str_c("tau[", 1:5, "]"), "beta[1]", "eta[1]") %>%

bind_rows(., .) %>%

mutate(male = rep(0:1, each = n() / 2)) %>%

# compute the conditional mu and sigma values

mutate(mu_i = 0 + male * `beta[1]`,

sigma_i = 1 / exp(0 + male * `eta[1]`)) %>%

# compute the p_k values conditional on the male dummy and the mu_i and sigma_i values

mutate(p1 = pnorm(`tau[1]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i),

p2 = pnorm(`tau[2]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i) - pnorm(`tau[1]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i),

p3 = pnorm(`tau[3]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i) - pnorm(`tau[2]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i),

p4 = pnorm(`tau[4]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i) - pnorm(`tau[3]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i),

p5 = pnorm(`tau[5]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i) - pnorm(`tau[4]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i),

p6 = 1 - pnorm(`tau[5]`, mean = mu_i, sd = sigma_i)) %>%

# the rest is now the same as before

pivot_longer(starts_with("p"), values_to = "p") %>%

mutate(rating = str_extract(name, "\\d") %>% as.double()) %>%

mutate(`p * rating` = p * rating) %>%

group_by(.draw, male) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = sum(`p * rating`)) %>%

mutate(sex = ifelse(male == 0, "female", "male")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = mean_rating, y = fct_rev(sex), fill = sex)) +

stat_halfeye(.width = .95) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_male, linetype = 2, color = "blue3") +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_female, linetype = 2, color = "red3") +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values = c(alpha("red3", 0.5), alpha("blue3", 0.5))) +

labs(title = "The postrior for the mean of the rating values, by sex",

subtitle = "The dashed vertical lines mark off the sample means, by sex. The posterior distributions\nare based on the simple conditional cumulative ordinal model fit3.",

x = expression(mu[rating]),

y = NULL) +

xlim(2, 4) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0))

The results are very similar to those from above.

Randomly-varying latent means.

Up until now, we’ve been ignoring how this model has a multilevel structure. We have ratings nested within persons (id) and questions (item). Within cumulative probit models, the simplest way to account for that nesting is to add random intercepts to the latent mean, which will now be \(\mu_{ij}\) for the \(i^\text{th}\) person and the \(j^\text{th}\) question.

Starting slow, we’ll first just add random intercepts for the persons with the model

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_i) & = \Phi(\tau_k - \mu_i) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_i) \\ \mu_i & = 0 + {\color{blue}{u_i}} \\ {\color{blue}{u_i}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\mathcal N(0, \sigma_u)}} \\ \tau_1 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_5 & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ {\color{blue}{\sigma_u}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{Exponential}(1)}}, \end{align*}

$$

where we’ve dropped the male predictor and the entire linear model for \(\log(\alpha_i)\) for the sake of simplicity. They’ll come back in a bit. Given the baseline fixed-effects portion of the model is still on the standardized-normal metric, the good old \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1)\) prior is a good choice for the level-2 standard deviation \(\sigma_u\). For more on the \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1)\) prior, see McElreath (

2020).

Here’s how to fit the model with brms.

# 49.94408 secs

fit4 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

rating ~ 1 + (1 | id),

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5),

prior(exponential(1), class = sd)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2

)

Check the summary.

print(fit4)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: rating ~ 1 + (1 | id)

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~id (Number of levels: 200)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1.03 0.07 0.90 1.18 1.00 1095 2370

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -1.33 0.10 -1.52 -1.15 1.00 1267 1809

## Intercept[2] -0.37 0.09 -0.54 -0.21 1.00 1286 2043

## Intercept[3] 0.09 0.09 -0.08 0.25 1.00 1278 1982

## Intercept[4] 1.04 0.09 0.86 1.22 1.00 1369 2298

## Intercept[5] 1.86 0.10 1.66 2.07 1.00 1665 2743

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

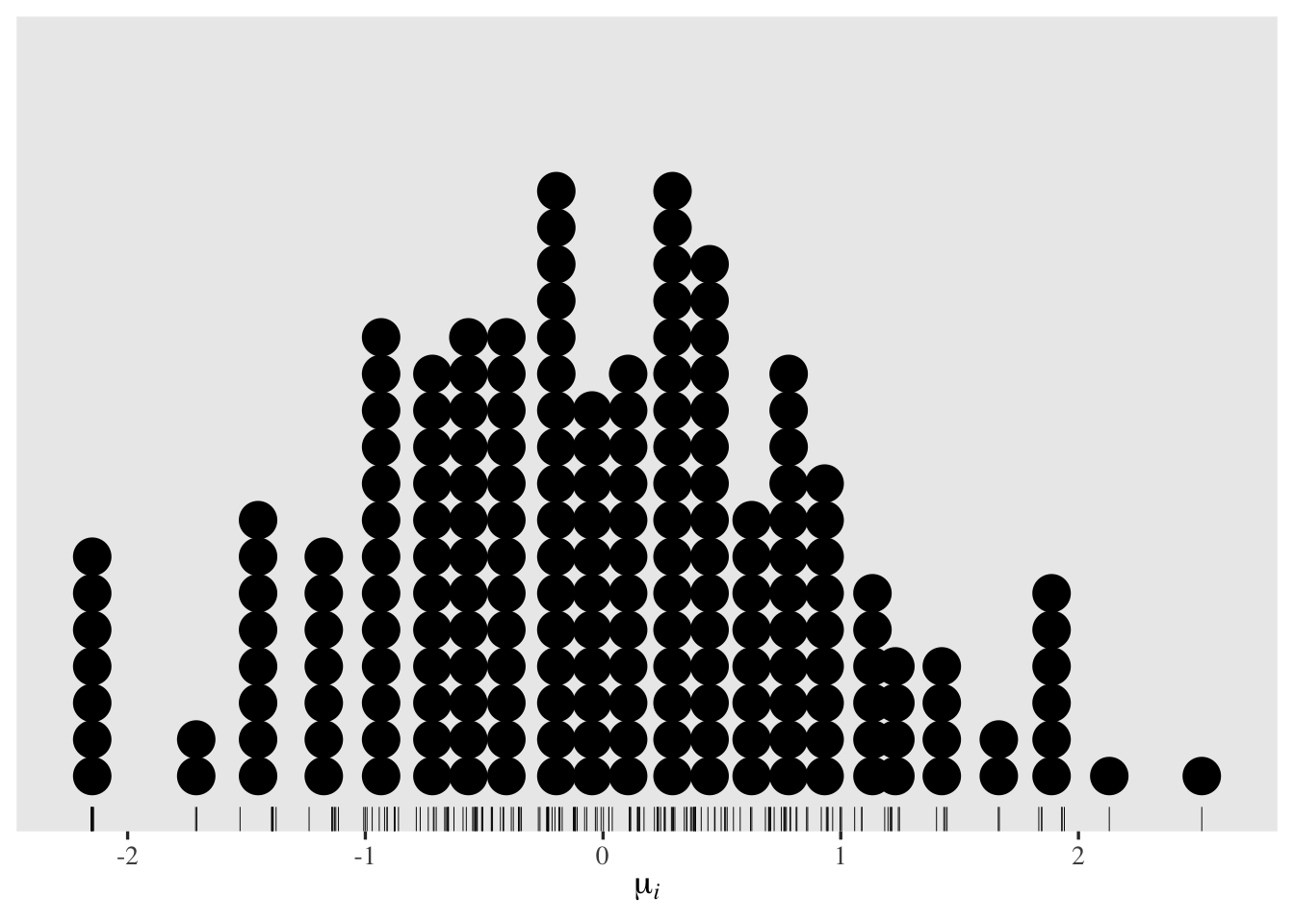

In this case, the \(u_i\) summaries from ranef() will be in the latent-mean metric. This is because the grand mean is still set to \(0\) for identification purposes. Here’s what the posterior means for those parameters look like in a dot plot.

tibble(ranef = ranef(fit4)$id[, 1, "Intercept"]) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = ranef)) +

geom_rug(linewidth = 1/6) +

geom_dotplot(binwidth = 1/6.5) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(expression(mu[italic(i)]))

Now it’s time to fit a proper cross-classified model accounting for the nesting within \(i\) persons and \(j\) questions. That will follow the equation

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_k \}, \mu_{i\color{blue}j}) & = \Phi(\tau_k - \mu_{i\color{blue}j}) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1} - \mu_{i\color{blue}j}) \\ \mu_{i\color{blue}j} & = 0 + u_i \color{blue}{ + } \color{blue}{v_j} \\ u_i & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_u) \\ {\color{blue}{v_j}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\mathcal N(0, \sigma_v)}} \\ \tau_1 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_2 & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_3 & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_4 & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_5 & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \sigma_u & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ {\color{blue}{\sigma_v}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{Exponential}(1)}}. \end{align*}

$$

At this point, we’re now fitting a Bayesian IRT model along the lines Bürkner showcased in his (

2020) tutorial. We have person-level parameters in \(u_i\) and item-level parameters in \(v_j\).

Fit the model.

# 1.278795 secs

fit5 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

rating ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item),

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5),

prior(exponential(1), class = sd)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2

)

Check the summary.

print(fit5)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: rating ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~id (Number of levels: 200)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1.04 0.07 0.91 1.19 1.00 1497 2029

##

## ~item (Number of levels: 5)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 0.21 0.12 0.07 0.52 1.00 1455 2003

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[1] -1.36 0.14 -1.64 -1.08 1.00 2167 2333

## Intercept[2] -0.38 0.13 -0.66 -0.13 1.00 2186 2486

## Intercept[3] 0.08 0.13 -0.19 0.34 1.00 2196 2537

## Intercept[4] 1.04 0.14 0.77 1.31 1.00 2396 2486

## Intercept[5] 1.88 0.15 1.59 2.17 1.00 2731 2506

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

Given there are only five levels of item, we should not be surprised the posterior for \(\sigma_v\) is much more uncertain relative to \(\sigma_u\). It should also not be shocking that the posterior for \(\sigma_v\) is also centered around a relatively small value. These five questions are all from the Neuroticism scale and psychologists tend to publish scales with relatively homogeneous items.

An issue that’s easy to miss with these two models is they’re holding the thresholds constant across both persons and items. At the moment, brms is not capable of hierarchically modeling the thresholds (see this thread), However, one can allow for differnt thresholds by question in a fixed-effects sort of way. Here’s what the updated statistical model would be

$$

\begin{align*} p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_{k\color{blue}j} \}, \mu_{ij}) & = \Phi(\tau_{k\color{blue}j} - \mu_{ij}) - \Phi(\tau_{k - 1,\color{blue}j} - \mu_{ij}) \\ \mu_{ij} & = 0 + u_i + v_j \\ u_i & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_u) \\ v_j & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_v) \\ \tau_{1\color{blue}j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_{2\color{blue}j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{3\color{blue}j} & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_{4\color{blue}j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{5\color{blue}j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \sigma_u & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_v & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1), \end{align*}

$$

where all the \(\tau\) parameters vary across the \(j\) levels of item. To fit such a model with brms, you use the thres(gr = <group>) helper function on the left-hand side of the model formula. If you want to continue to manually set different priors for the thresholds, you’ll now need to include the group argument within the prior() function. In my experience, don’t be surprised if you have to adjust adapt_delta at this point.

# 3.59341 mins

fit6 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

rating | thres(gr = item) ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item),

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N1),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N2),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N2),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N3),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N3),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N4),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N4),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N5),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N5),

prior(exponential(1), class = sd)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2,

control = list(adapt_delta = .99)

)

The summary is now quite lengthy.

print(fit6)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = identity

## Formula: rating | thres(gr = item) ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~id (Number of levels: 200)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1.06 0.08 0.91 1.22 1.01 1416 2119

##

## ~item (Number of levels: 5)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 0.23 0.20 0.01 0.73 1.00 1523 2400

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[N1,1] -1.30 0.25 -1.87 -0.85 1.00 2717 2195

## Intercept[N1,2] -0.46 0.24 -1.02 -0.02 1.00 2776 2162

## Intercept[N1,3] -0.01 0.24 -0.57 0.43 1.00 2809 2281

## Intercept[N1,4] 1.12 0.25 0.56 1.57 1.00 3028 2808

## Intercept[N1,5] 1.99 0.27 1.40 2.47 1.00 3520 2772

## Intercept[N2,1] -1.80 0.26 -2.33 -1.27 1.00 3003 2569

## Intercept[N2,2] -0.64 0.24 -1.14 -0.15 1.00 3191 2365

## Intercept[N2,3] -0.13 0.23 -0.64 0.35 1.00 3103 2017

## Intercept[N2,4] 0.73 0.24 0.24 1.24 1.00 3093 2758

## Intercept[N2,5] 1.75 0.25 1.24 2.28 1.00 3717 3134

## Intercept[N3,1] -1.43 0.25 -2.02 -0.99 1.00 2855 2498

## Intercept[N3,2] -0.34 0.24 -0.90 0.10 1.00 2965 2563

## Intercept[N3,3] 0.04 0.24 -0.51 0.48 1.00 3047 2545

## Intercept[N3,4] 1.08 0.25 0.52 1.52 1.00 3096 2459

## Intercept[N3,5] 1.82 0.26 1.23 2.28 1.00 3424 2966

## Intercept[N4,1] -1.47 0.25 -2.03 -0.99 1.00 2880 2575

## Intercept[N4,2] -0.58 0.24 -1.15 -0.13 1.00 3112 2709

## Intercept[N4,3] -0.00 0.24 -0.54 0.45 1.00 3084 2786

## Intercept[N4,4] 0.96 0.24 0.41 1.42 1.00 3264 2669

## Intercept[N4,5] 1.89 0.27 1.32 2.39 1.00 3730 2695

## Intercept[N5,1] -1.18 0.25 -1.76 -0.74 1.00 2872 2875

## Intercept[N5,2] -0.23 0.24 -0.80 0.20 1.00 3071 2772

## Intercept[N5,3] 0.22 0.24 -0.34 0.67 1.00 3108 2855

## Intercept[N5,4] 1.04 0.24 0.48 1.48 1.00 3392 3014

## Intercept[N5,5] 1.68 0.26 1.09 2.18 1.00 3633 2985

##

## Family Specific Parameters:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## disc 1.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 NA NA NA

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

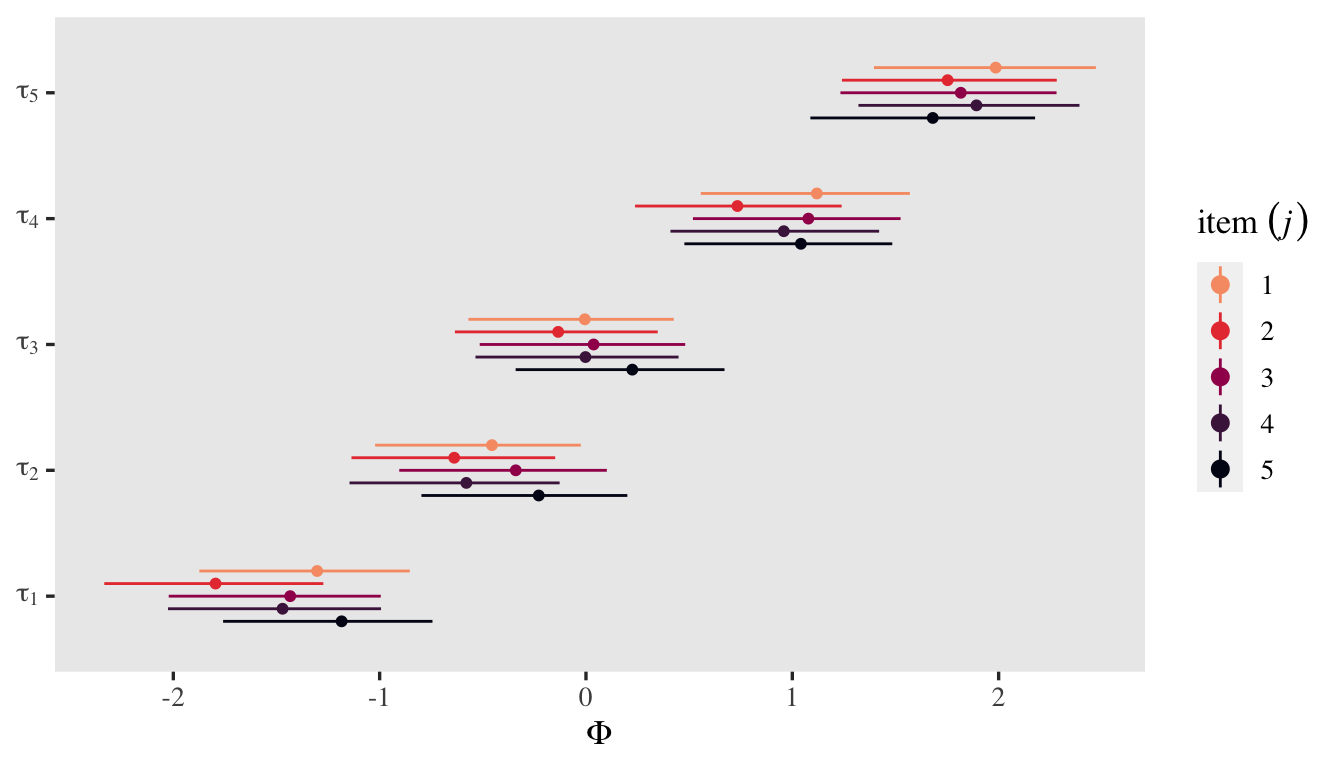

It might be easier to get a sense of the \(\tau_{kj}\) posteriors with a coefficient plot.

posterior_summary(fit6)[1:25, ] %>%

data.frame() %>%

mutate(tau = rep(1:5, times = 5),

item = rep(1:5, each = 5)) %>%

mutate(tau = str_c("tau[", tau, "]"),

item = factor(item)) %>%

ggplot(aes(y = Estimate, ymin = Q2.5, ymax = Q97.5, x = tau,

group = item, color = item)) +

geom_pointrange(position = position_dodge(width = -0.5), fatten = 1.5) +

scale_color_viridis_d(expression(item~(italic(j))), option = "F", end = 0.8, direction = -1) +

scale_x_discrete(NULL, labels = ggplot2:::parse_safe) +

coord_flip() +

ylab(expression(Phi))

You could use information criteria comparisons to decide on whether to allow them to vary across items or if it’s okay to prefer the more parsimonious model. IMO, thresholds across items are a priori different and should not be collapsed without strong theoretical or methodological justifications. In this case, it seems like I lose nothing by having them.

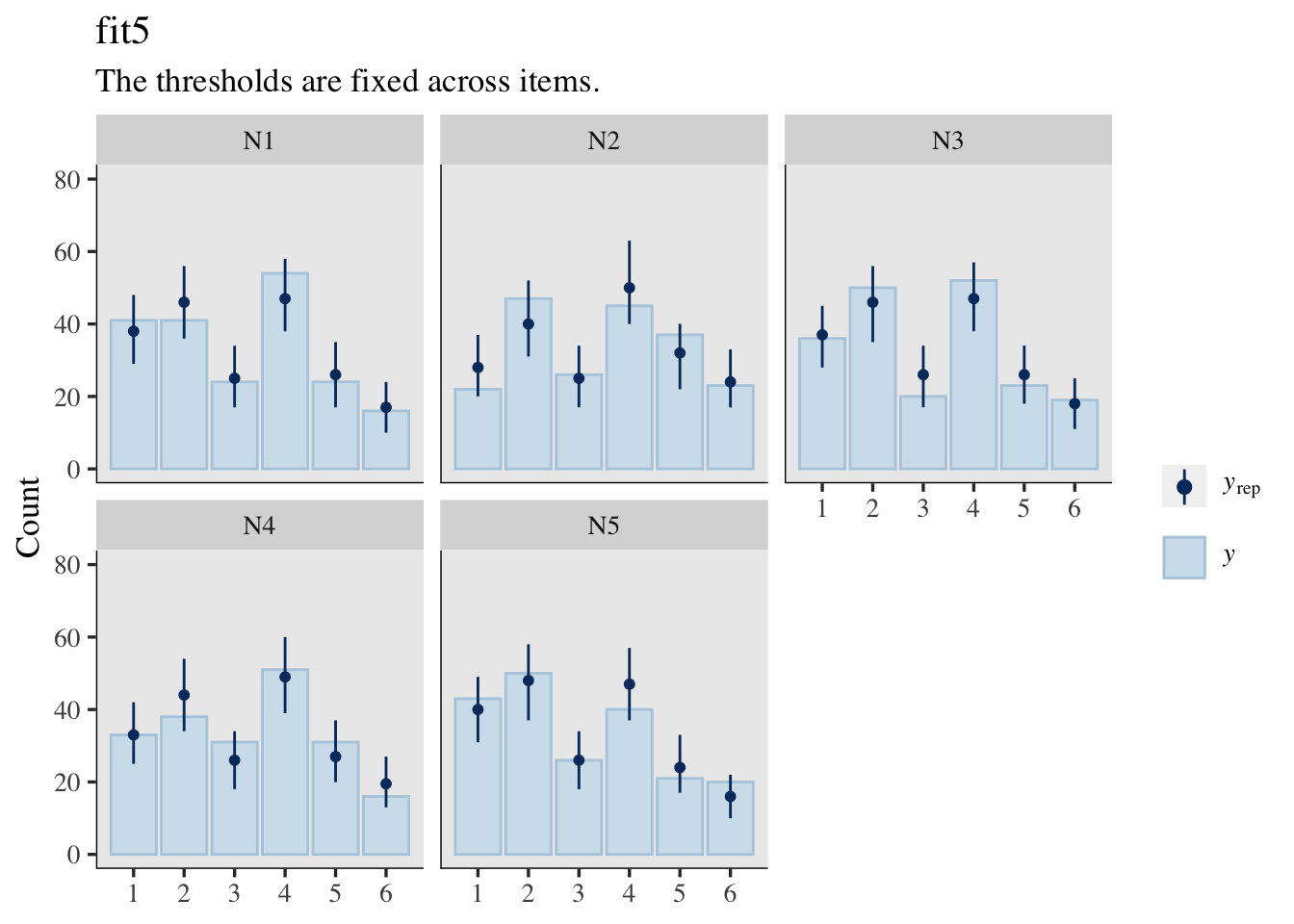

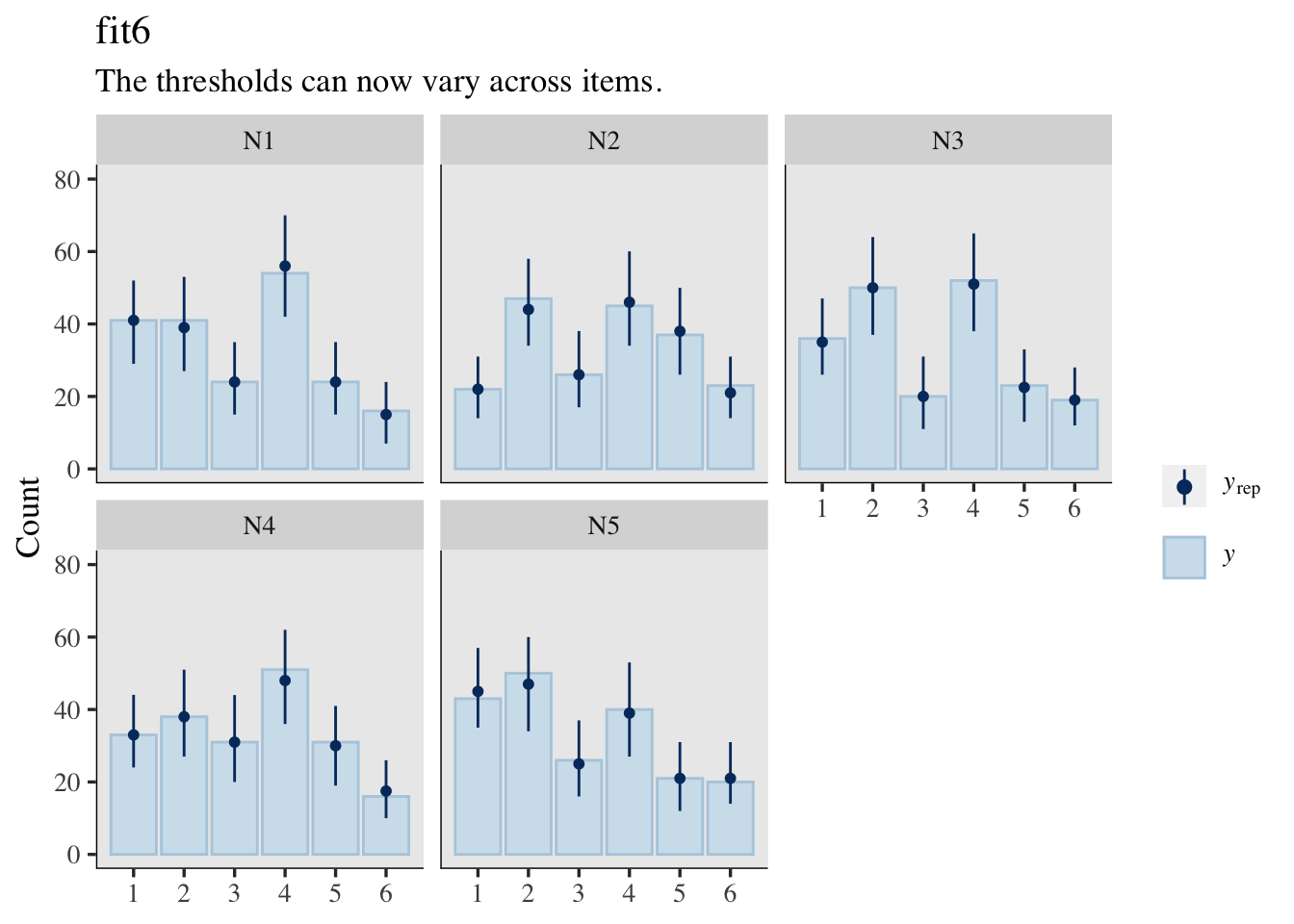

Plus, there’s also the implications of the varying thresholds for the posterior-predictive distributions.

set.seed(1)

pp_check(fit5, type = "bars_grouped", group = "item",

ndraws = 500, size = 1/2, fatten = 3/2) +

ylim(0, 80) +

labs(title = "fit5",

subtitle = "The thresholds are fixed across items.")

set.seed(1)

pp_check(fit6, type = "bars_grouped", group = "item",

ndraws = 500, size = 1/2, fatten = 3/2) +

ylim(0, 80) +

labs(title = "fit6",

subtitle = "The thresholds can now vary across items.")

Well okay, maybe I do lose something by letting the thresholds vary across questions. If you look at the parameter summaries for fit5 and fit6, you’ll see the posterior standard deviations (see the Est.Error columns) are wider in fit6. This corresponds to the wider prediction intervals in the pp_check() plot for fit6, compared to the plot for fit5. You might think of this as trade-off of accuracy for precision or of reliability for validity. IMO, the trade-off was worth it. Allowing the thresholds to vary across the items makes for much better posterior predictions.

Randomly-varying latent standard deviations.

If the latent means can vary randomly, the latent dispersion parameters can vary randomly, too. Now \(\log(\alpha_{ij})\) will vary across \(i\) persons and \(j\) questions with the Bayesian ordinal IRT model

$$

\begin{align*} \small{p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_{kj} \}, \mu_{ij}, {\color{blue}{\alpha_{ij}}})} & = \small{\Phi({\color{blue}{\alpha_{ij}}} [\tau_{kj} - \mu_{ij}]) - \Phi( {\color{blue}{\alpha_{ij}}} [\tau_{k - 1,j} - \mu_{ij}])} \\ \mu_{ij} & = 0 + u_i + v_j \\ {\color{blue}{\log(\alpha_{ij})}} & = {\color{blue}{0 + w_i + x_j}} \\ u_i & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_u) \\ v_j & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_v) \\ {\color{blue}{w_i}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\mathcal N(0, \sigma_w)}} \\ {\color{blue}{x_j}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\mathcal N(0, \sigma_x)}} \\ \tau_{1j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_{2j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{3j} & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_{4j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{5j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \sigma_u & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_v & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ {\color{blue}{\sigma_w}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{Exponential}(1)}} \\ {\color{blue}{\sigma_x}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{Exponential}(1)}} . \end{align*}

$$

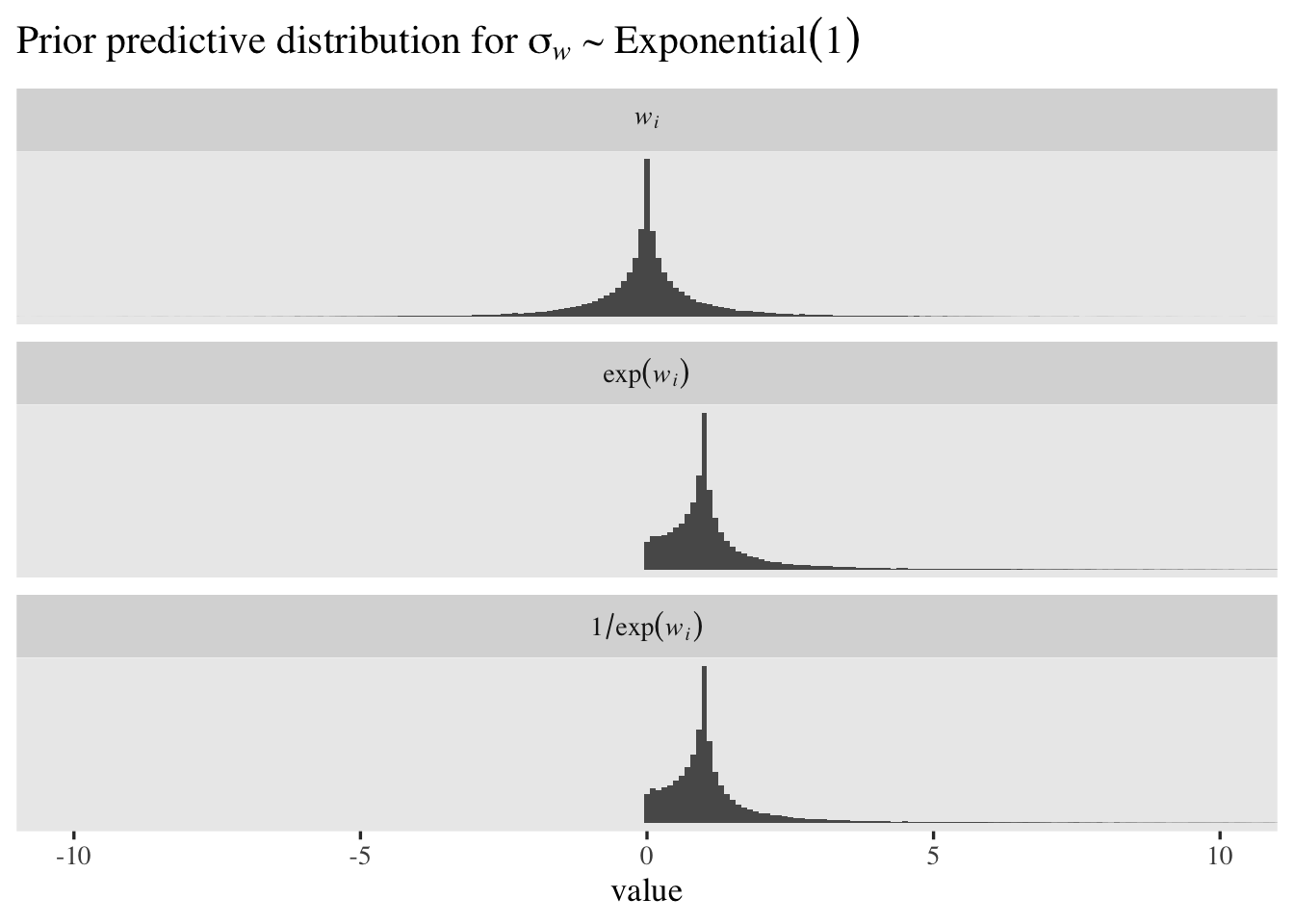

Though the \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1)\) prior might be a good place to start with our new \(\sigma_w\) and \(\sigma_x\), let’s ponder this a bit. Recall these are for the distribution of logged discrimination parameters. Since I’m no statistician or psychometrician, I’m not even sure what that means, which makes it hard to intuit whether the \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1)\) prior makes sense for my data. A plot might help. Here we’ll simulate \(100{,}000\) draws from the \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1)\) prior, use those draws to simulate \(w_i\) values from \(\mathcal N(0, \sigma_w)\), and then plot that distribution in the \(w_i\), \(\exp(w_i)\) and \(1/\exp(w_i)\) metrics.

set.seed(1)

# simulate from the prior

tibble(sigma_w = rexp(n = 1e5, rate = 1)) %>%

# simulate w_i draws

mutate(`italic(w[i])` = rnorm(n = n(), mean = 0, sd = sigma_w)) %>%

# transform

mutate(`exp(italic(w[i]))` = exp(`italic(w[i])`)) %>%

mutate(`1/exp(italic(w[i]))` = 1 / `exp(italic(w[i]))`) %>%

# wrangle

pivot_longer(-sigma_w) %>%

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = c("italic(w[i])", "exp(italic(w[i]))", "1/exp(italic(w[i]))"))) %>%

# for computational simplicity, remove some values from the far right tail

filter(value < 100) %>%

# plot!

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.1) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-10, 10)) +

ggtitle(expression("Prior predictive distribution for "*sigma[italic(w)]%~%Exponential(1))) +

facet_wrap(~ name, labeller = label_parsed, ncol = 1)

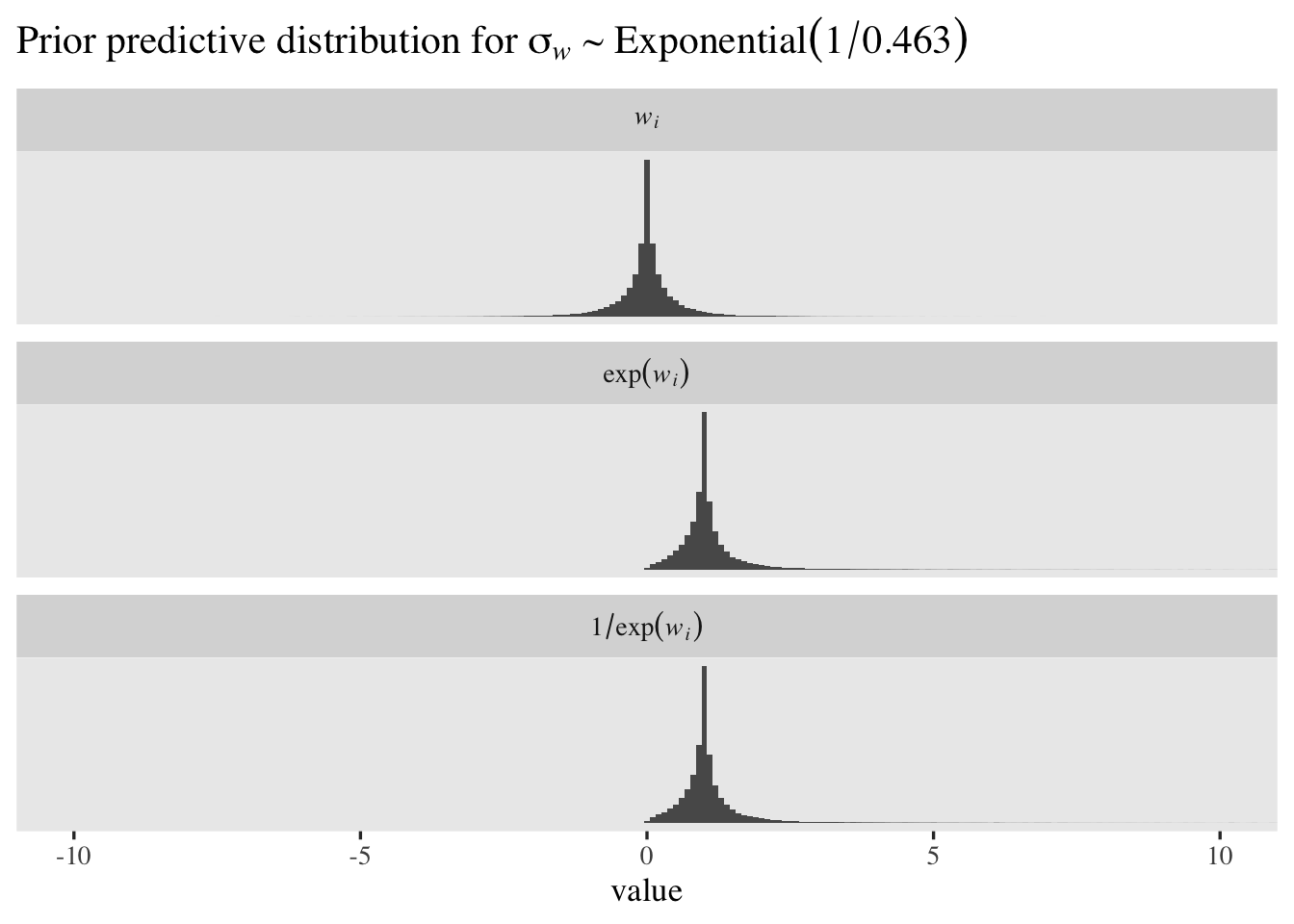

The mean and median for \(w_i\) are both zero. Because of the very long right tails, both \(\exp(w_i)\) and \(1/\exp(w_i)\) have very large means and standard deviations. However, both \(\exp(w_i)\) and \(1/\exp(w_i)\) have medians at \(1\). The \(1/\exp(w_i)\) distribution is the one that’s in the latent \(\sigma\) metric and its percentile-based 95% interval ranges from \(0.05\) to \(20.28\). That isn’t bad for a permissive level-2 standard deviation prior, but I think we can do better. If we set the mean of the exponential prior to \(0.463\), the resulting prior-predictive distribution of \(1/\exp(w_i)\) will have a percentile-based 95% interval of \(0.25\) to \(4\). Here’s what that looks like.

set.seed(1)

# save for this first line, this workflow is the same as before

tibble(sigma_w = rexp(n = 1e5, rate = 1 / 0.463)) %>%

mutate(`italic(w[i])` = rnorm(n = n(), mean = 0, sd = sigma_w)) %>%

mutate(`exp(italic(w[i]))` = exp(`italic(w[i])`)) %>%

mutate(`1/exp(italic(w[i]))` = 1 / `exp(italic(w[i]))`) %>%

pivot_longer(-sigma_w) %>%

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = c("italic(w[i])", "exp(italic(w[i]))", "1/exp(italic(w[i]))"))) %>%

filter(value < 100) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.1) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-10, 10)) +

ggtitle(expression("Prior predictive distribution for "*sigma[italic(w)]%~%Exponential(1/0.463))) +

facet_wrap(~ name, labeller = label_parsed, ncol = 1)

With that as our prior, our updated model formula will be

$$

\begin{align*} \small{p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_{kj} \}, \mu_{ij}, \alpha_{ij})} & = \small{\Phi(\alpha_{ij}[\tau_{kj} - \mu_{ij}]) - \Phi(\alpha_{ij}[\tau_{k - 1,j} - \mu_{ij}])} \\ \mu_{ij} & = 0 + u_i + v_j \\ \log(\alpha_{ij}) & = 0 + w_i + x_j \\ u_i & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_u) \\ v_j & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_v) \\ w_i & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_w) \\ x_j & \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_x) \\ \tau_{1j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_{2j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{3j} & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_{4j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{5j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \sigma_u & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_v & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_w & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}({\color{blue}{1 / 0.463}} ) \\ \sigma_x & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}({\color{blue}{1 / 0.463}} ). \end{align*}

$$

Put those new priors to work and fit the model.

# 5.223564 mins

fit7 <- brm(

data = d,

family = cumulative(probit),

bf(rating | thres(gr = item) ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)) +

lf(disc ~ 0 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)),

prior = c(prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N1),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N1),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N1),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N2),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N2),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N2),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N3),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N3),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N3),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N4),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N4),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N4),

prior(normal(-0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 1, group = N5),

prior(normal(-0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 2, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.00, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 3, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.43, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 4, group = N5),

prior(normal( 0.97, 1), class = Intercept, coef = 5, group = N5),

prior(exponential(1), class = sd),

# here's the fancy new prior line

prior(exponential(1 / 0.463), class = sd, dpar = disc)),

cores = 4,

seed = 1,

init_r = 0.2,

control = list(adapt_delta = .99)

)

Summarize.

print(fit7)

## Family: cumulative

## Links: mu = probit; disc = log

## Formula: rating | thres(gr = item) ~ 1 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)

## disc ~ 0 + (1 | id) + (1 | item)

## Data: d (Number of observations: 1000)

## Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

## total post-warmup draws = 4000

##

## Group-Level Effects:

## ~id (Number of levels: 200)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 1.19 0.14 0.92 1.49 1.00 567 1045

## sd(disc_Intercept) 0.44 0.06 0.34 0.56 1.00 1322 2459

##

## ~item (Number of levels: 5)

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## sd(Intercept) 0.26 0.23 0.01 0.85 1.00 1451 1997

## sd(disc_Intercept) 0.42 0.18 0.17 0.87 1.00 1101 1271

##

## Population-Level Effects:

## Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

## Intercept[N1,1] -1.32 0.30 -1.99 -0.77 1.00 1191 2072

## Intercept[N1,2] -0.50 0.26 -1.09 -0.02 1.00 2149 2864

## Intercept[N1,3] -0.06 0.25 -0.65 0.41 1.00 2637 2862

## Intercept[N1,4] 1.04 0.28 0.40 1.56 1.00 1859 3117

## Intercept[N1,5] 1.91 0.35 1.21 2.60 1.00 1311 2212

## Intercept[N2,1] -1.81 0.33 -2.47 -1.17 1.00 1012 2135

## Intercept[N2,2] -0.60 0.25 -1.08 -0.09 1.00 2020 2854

## Intercept[N2,3] -0.12 0.24 -0.58 0.40 1.00 2941 2942

## Intercept[N2,4] 0.69 0.25 0.21 1.21 1.00 2323 2732

## Intercept[N2,5] 1.67 0.32 1.07 2.34 1.00 1441 2250

## Intercept[N3,1] -1.52 0.33 -2.28 -0.96 1.00 980 1378

## Intercept[N3,2] -0.36 0.27 -0.98 0.11 1.00 1980 2461

## Intercept[N3,3] 0.03 0.26 -0.56 0.51 1.00 2597 2703

## Intercept[N3,4] 1.18 0.29 0.55 1.74 1.00 2283 2869

## Intercept[N3,5] 2.08 0.37 1.36 2.83 1.00 1519 2576

## Intercept[N4,1] -1.89 0.36 -2.63 -1.24 1.00 1058 2321

## Intercept[N4,2] -0.73 0.28 -1.35 -0.23 1.00 2103 2903

## Intercept[N4,3] -0.02 0.26 -0.59 0.47 1.00 3276 3331

## Intercept[N4,4] 1.21 0.30 0.58 1.81 1.00 2084 2892

## Intercept[N4,5] 2.57 0.44 1.74 3.50 1.00 1276 2514

## Intercept[N5,1] -1.66 0.37 -2.53 -1.07 1.00 1009 1687

## Intercept[N5,2] -0.35 0.29 -1.04 0.13 1.00 2181 2105

## Intercept[N5,3] 0.25 0.29 -0.42 0.74 1.00 2767 2573

## Intercept[N5,4] 1.40 0.34 0.68 2.04 1.00 2143 2835

## Intercept[N5,5] 2.40 0.42 1.58 3.25 1.00 1596 2798

##

## Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

## and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

## scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

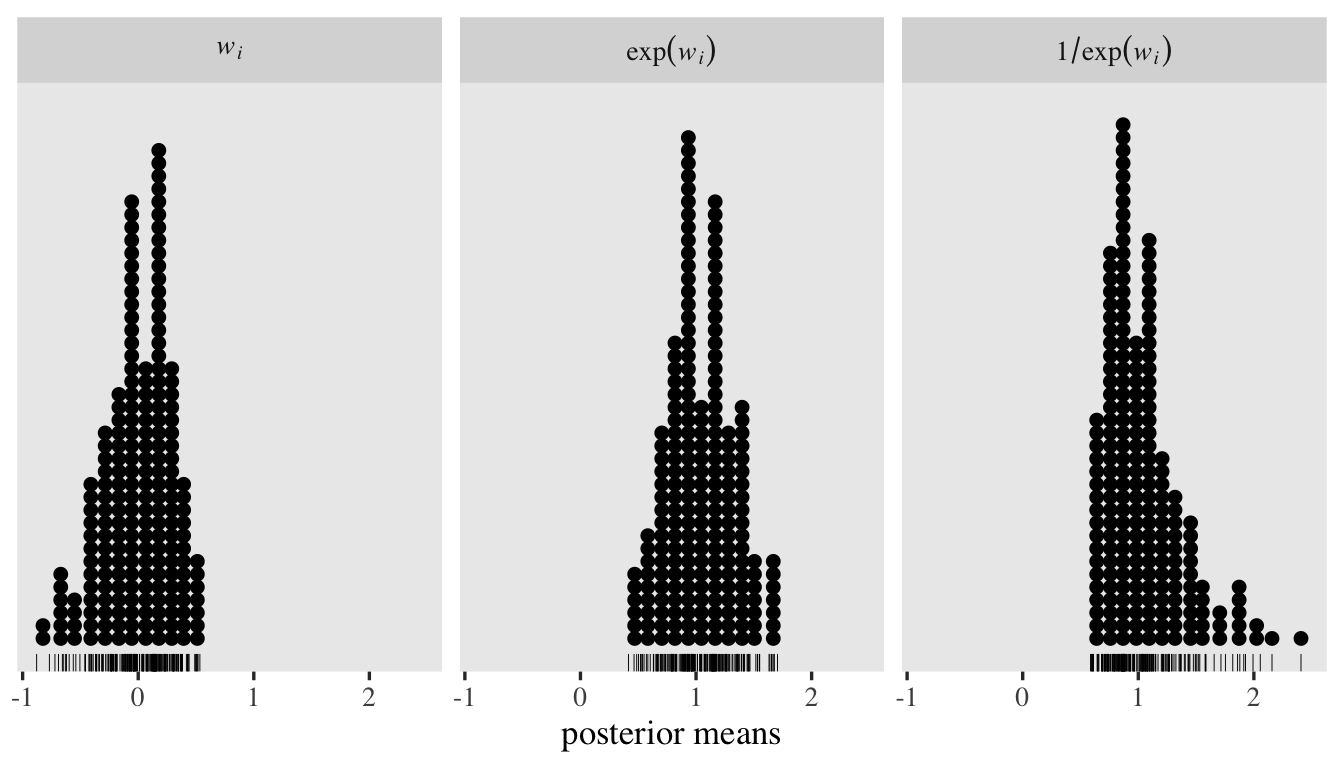

To get a better sense of what those new level-2 random \(\log(\alpha_{ij})\) standard deviation estimates mean, let’s focus on the posterior for \(\sigma_w\), which is \(0.44, 95\% \text{CI}\ [0.34, 0.56]\). We can use the ranef() function to pull the summary statistics for the corresponding \(w_i\) posteriors. To simplify things, we’ll just focus on the posterior means. After pulling the summaries, we’ll place them within a tibble, transform them to the \(\exp(w_i)\) and \(1 / \exp(w_i)\) metrics, and then plot like with the prior predictive distributions, before. But since we only have \(200\) values to visualize, this time, we’ll use dot plots.

tibble(`italic(w[i])` = ranef(fit7)$id[, 1, "disc_Intercept"]) %>%

mutate(`exp(italic(w[i]))` = exp(`italic(w[i])`)) %>%

mutate(`1/exp(italic(w[i]))` = 1 / exp(`italic(w[i])`)) %>%

pivot_longer(everything()) %>%

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = c("italic(w[i])", "exp(italic(w[i]))", "1/exp(italic(w[i]))"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

geom_rug(linewidth = 1/6) +

geom_dotplot(binwidth = 1/9) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab("posterior means") +

facet_wrap(~ name, labeller = label_parsed)

Now we turn to the task of using the model to compute the means of the rating variable, this time separately for each of the \(5\) Neuroticism items. One could generalized the workflow we used for fit1 through fit3, but I wouldn’t recommend that. The brms::fitted() function will be our friend, here. Though ultimately we’ll want to use fitted() with summary = FALSE, I’m going to save the results both ways to help explain the output.

# define the new data

nd <- d %>% distinct(item)

# save the summarized results

f_summary <-

fitted(fit7,

newdata = nd,

# note this line

re_formula = ~ (1 | item))

# save the un-summarized results

f <-

fitted(fit7,

newdata = nd,

re_formula = ~ (1 | item),

summary = F)

First take a look at the structure of f_summary.

f_summary %>% str()

## num [1:5, 1:4, 1:6] 0.0423 0.0055 0.0852 0.0998 0.1538 ...

## - attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 3

## ..$ : NULL

## ..$ : chr [1:4] "Estimate" "Est.Error" "Q2.5" "Q97.5"

## ..$ : chr [1:6] "P(Y = 1)" "P(Y = 2)" "P(Y = 3)" "P(Y = 4)" ...

We have a \(3\)-dimensional array. The \(5\) levels of the first dimension are the \(5\) levels of item. The \(4\) levels of the second dimension are the typical summary statistics, the posterior mean through the upper-level of the 95% CI. The \(6\) levels of the third dimension let us divide up the results by the \(6\) levels of \(k\), the rating levels 1 through 6.

But we don’t want summarized results. We want the posterior draws. Enter f.

f %>% str()

## num [1:4000, 1:5, 1:6] 0.0644 0.049 0.0359 0.0493 0.0258 ...

## - attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 3

## ..$ : chr [1:4000] "1" "2" "3" "4" ...

## ..$ : NULL

## ..$ : chr [1:6] "1" "2" "3" "4" ...

Now the dimension within the array is the \(4{,}000\) posterior draws. The second dimension is our \(5\) levels of item and the third dimension the \(6\) levels of \(k\). Before we put this all to use, we’ll want to save a few values as external objects for the plotting.

# sample means for the items

m_n1 <- d %>% filter(item == "N1") %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

m_n2 <- d %>% filter(item == "N2") %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

m_n3 <- d %>% filter(item == "N3") %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

m_n4 <- d %>% filter(item == "N4") %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

m_n5 <- d %>% filter(item == "N5") %>% summarise(m = mean(rating)) %>% pull()

# save color values for the geom_vline() lines

colors <- viridis::viridis_pal(option = "A", end = 0.85, direction = -1)(5)

Okay, within rbind(), we serially stack the levels of the third dimension within the f array so we can use our tidyverse-style wrangling. Then the workflow looks a lot like before.

rbind(f[, , 1],

f[, , 2],

f[, , 3],

f[, , 4],

f[, , 5],

f[, , 6]) %>%

data.frame() %>%

set_names(str_c("N", 1:5)) %>%

mutate(draw = rep(1:4000, times = 6),

rating = rep(1:6, each = 4000)) %>%

pivot_longer(N1:N5, names_to = "item", values_to = "p") %>%

mutate(`p * k` = p * rating) %>%

group_by(draw, item) %>%

summarise(mean_rating = sum(`p * k`)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = mean_rating, y = fct_rev(item), fill = item)) +

stat_halfeye(.width = .95) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_n1, linetype = 2, color = colors[1]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_n2, linetype = 2, color = colors[2]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_n3, linetype = 2, color = colors[3]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_n4, linetype = 2, color = colors[4]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_n5, linetype = 2, color = colors[5]) +

scale_fill_viridis_d(NULL, option = "A", end = 0.85, direction = -1, alpha = 2/3) +

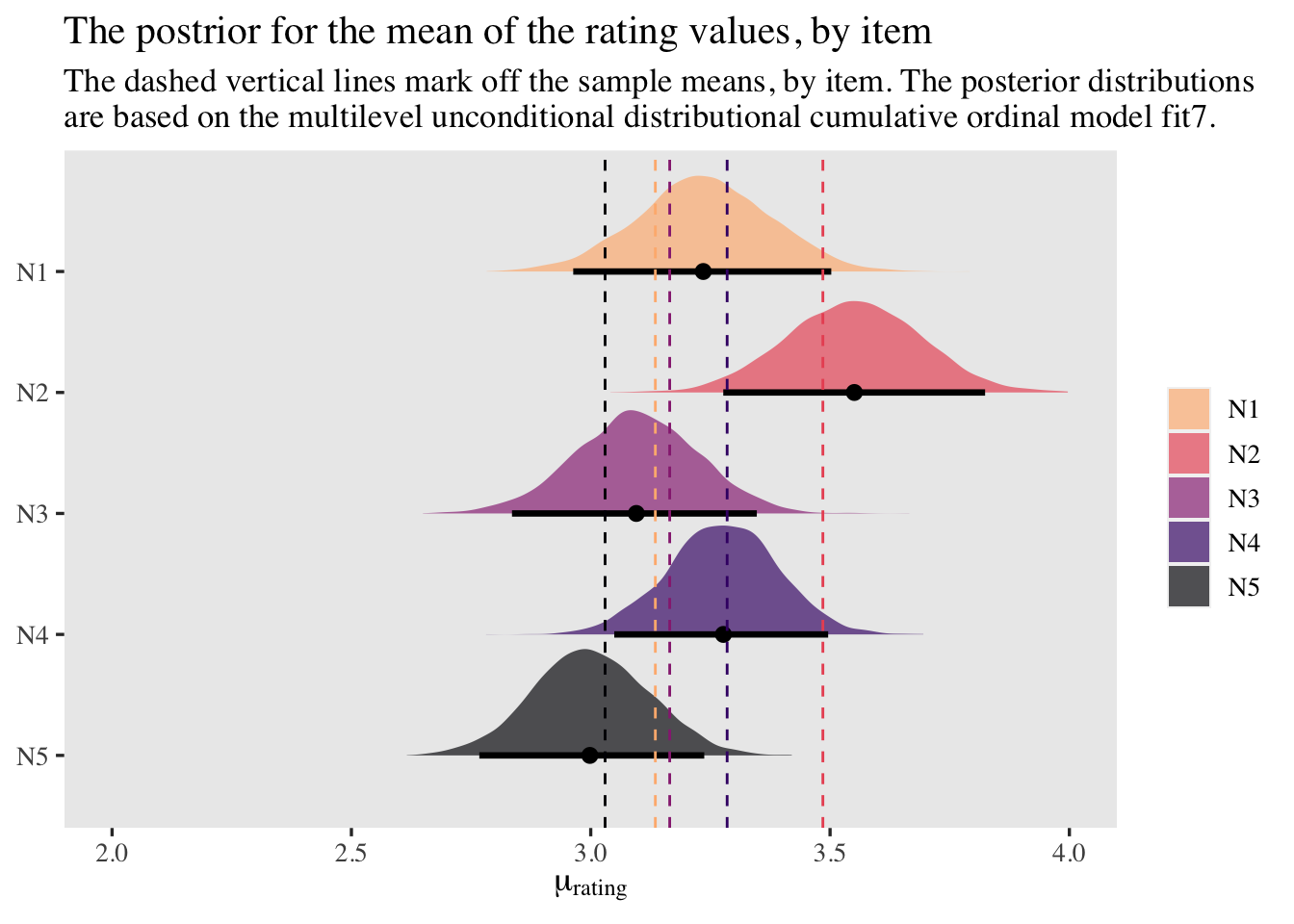

labs(title = "The postrior for the mean of the rating values, by item",

subtitle = "The dashed vertical lines mark off the sample means, by item. The posterior distributions\nare based on the multilevel unconditional distributional cumulative ordinal model fit7.",

x = expression(mu[rating]),

y = NULL) +

xlim(2, 4)

At first glance, it might be upsetting that out posteriors for the item-level means no longer tightly line up with the sample means. However, keep in mind these were computed with a multilevel model, which will impose partial pooling toward the grand mean. Based on decades of hard work within statistics (see Efron & Morris, 1977), we know that our partially-pooled means will be more likely generalize to new data than our sample means. This is why we model. Though we do want to understand our sample data, we also want to make inferences about other data from the population.

Now that we have a full model accounting for all five Neuroticism items, we can use a similar approach to compute the population-level sum score. First, we’ll compute the sample mean of the sum score and save the value as m_sum_score.

m_sum_score <- d %>%

group_by(id) %>%

summarise(sum = sum(rating)) %>%

summarise(mean_sum = mean(sum)) %>%

pull()

# what's the value?

m_sum_score

## [1] 16.1

Next we make a small amendment the workflow above. Instead of grouping by posterior draw and by item before the summarise() line, this time we only group by draw. As a consequence, the values for all the items will be summed within each posterior draw, making a vector of sum scores. Then we plot.

rbind(f[, , 1],

f[, , 2],

f[, , 3],

f[, , 4],

f[, , 5],

f[, , 6]) %>%

data.frame() %>%

set_names(str_c("N", 1:5)) %>%

mutate(draw = rep(1:4000, times = 6),

rating = rep(1:6, each = 4000)) %>%

pivot_longer(N1:N5, names_to = "item", values_to = "p") %>%

mutate(`p * k` = p * rating) %>%

# notice we are no longer grouping by draw AND item

group_by(draw) %>%

summarise(mean_sum_score = sum(`p * k`)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = mean_sum_score, y = 0)) +

stat_halfeye(.width = .95) +

geom_vline(xintercept = m_sum_score, linetype = 2) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

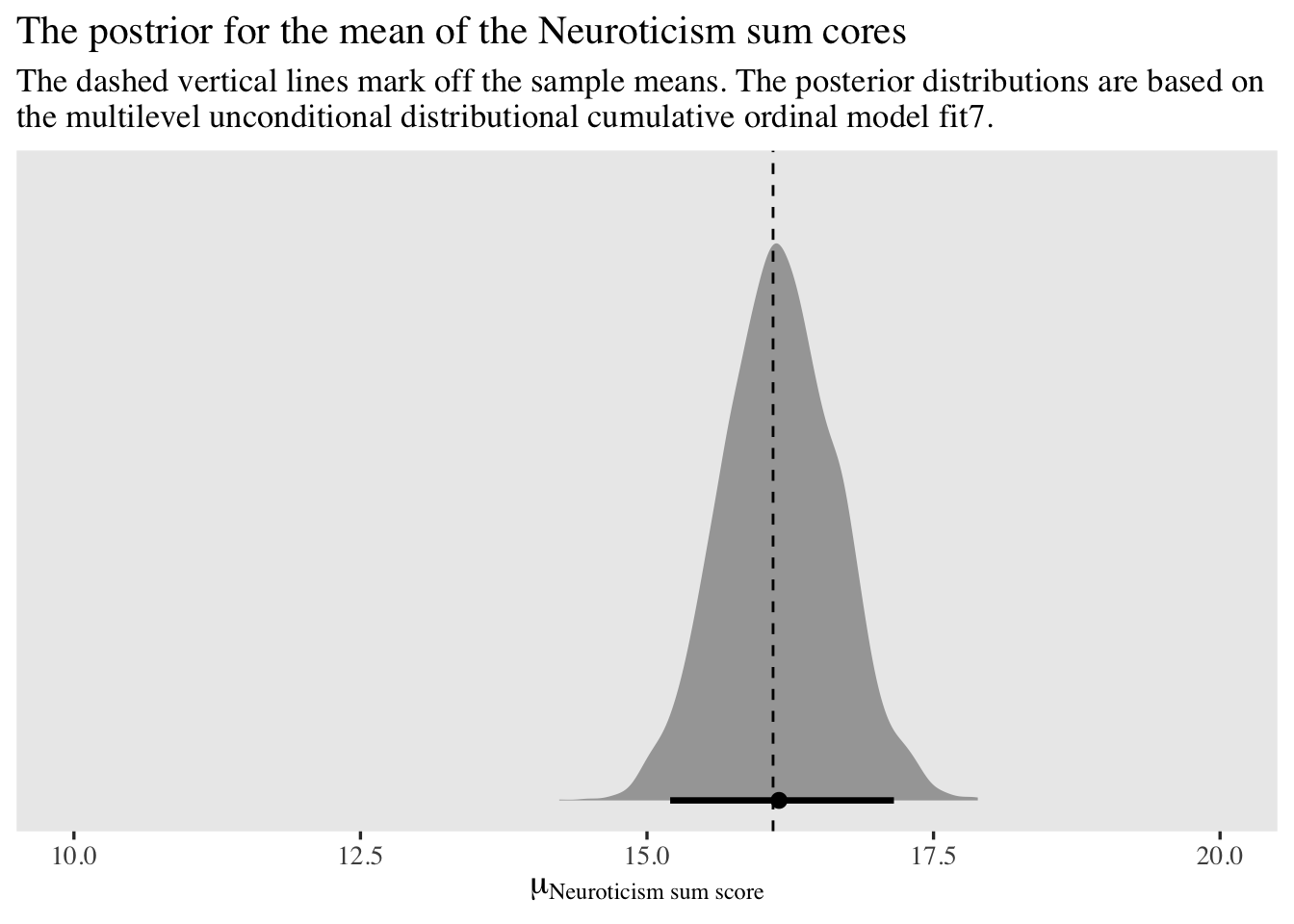

labs(title = "The postrior for the mean of the Neuroticism sum cores",

subtitle = "The dashed vertical lines mark off the sample means. The posterior distributions are based on\nthe multilevel unconditional distributional cumulative ordinal model fit7.",

x = expression(mu[Neuroticism~sum~score]),

y = NULL) +

xlim(10, 20)

The model does a great job capturing the Neuroticism sum scores.

Now if you wanted to, you could expand this model further to include correlations between \(u_i\) and \(w_i\) and between \(v_j\) and \(x_j\). That would change the model formula to something like

$$

\begin{align*} \small{p(\text{rating} = k | \{ \tau_{kj} \}, \mu_{ij}, \alpha_{ij})} & = \small{\Phi(\alpha_{ij}[\tau_{kj} - \mu_{ij}]) - \Phi(\alpha_{ij}[\tau_{k - 1,j} - \mu_{ij}])} \\ \mu_{ij} & = 0 + u_i + v_j \\ \log(\alpha_{ij}) & = 0 + w_i + x_j \\ \begin{bmatrix} u_i \\ w_i \end{bmatrix} & \sim \mathcal{MVN}(\mathbf 0, \mathbf{S_a {\color{blue}{R_a}} S_a}) \\ \begin{bmatrix} v_j \\ x_j \end{bmatrix} & \sim \mathcal{MVN}(\mathbf 0, \mathbf{S_b {\color{blue}{R_b}} S_b}) \\ \mathbf{S_a} & = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_u & 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_w \end{bmatrix} \\ \mathbf{S_b} & = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_v & 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_x \end{bmatrix} \\ {\color{blue}{\mathbf{R_a}}} & = {\color{blue}{\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \rho_a \\ \rho_a & 1 \end{bmatrix}}} \\ {\color{blue}{\mathbf{R_b}}} & = {\color{blue}{\begin{bmatrix} 1 & \rho_b \\ \rho_b & 1 \end{bmatrix}}} \\ \tau_{1j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.97, 1) \\ \tau_{2j} & \sim \mathcal N(-0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{3j} & \sim \mathcal N(0, 1) \\ \tau_{4j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.43, 1) \\ \tau_{5j} & \sim \mathcal N(0.97, 1) \\ \sigma_u & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_v & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1) \\ \sigma_w & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1 / 0.463) \\ \sigma_x & \sim \operatorname{Exponential}(1 / 0.463) \\ {\color{blue}{\rho_a}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{LKJ}(2)}} \\ {\color{blue}{\rho_b}} & \sim {\color{blue}{\operatorname{LKJ}(2)}}, \end{align*}

$$

where though our four random parameters are now modeled as two bivariate-normal pairs, there really are only two new parameters: \(\rho_a\) and \(\rho_b\). The LKJ priors for our two new parameters would be weakly regularizing. In my experience, so far, adding those two level-2 correlations can make for notably longer fitting times and they often result in computational complications like the need to further adjust adapt_delta and so on. So in the interest of space, I’m not going to fit this model. But it’s always a possibility to consider.

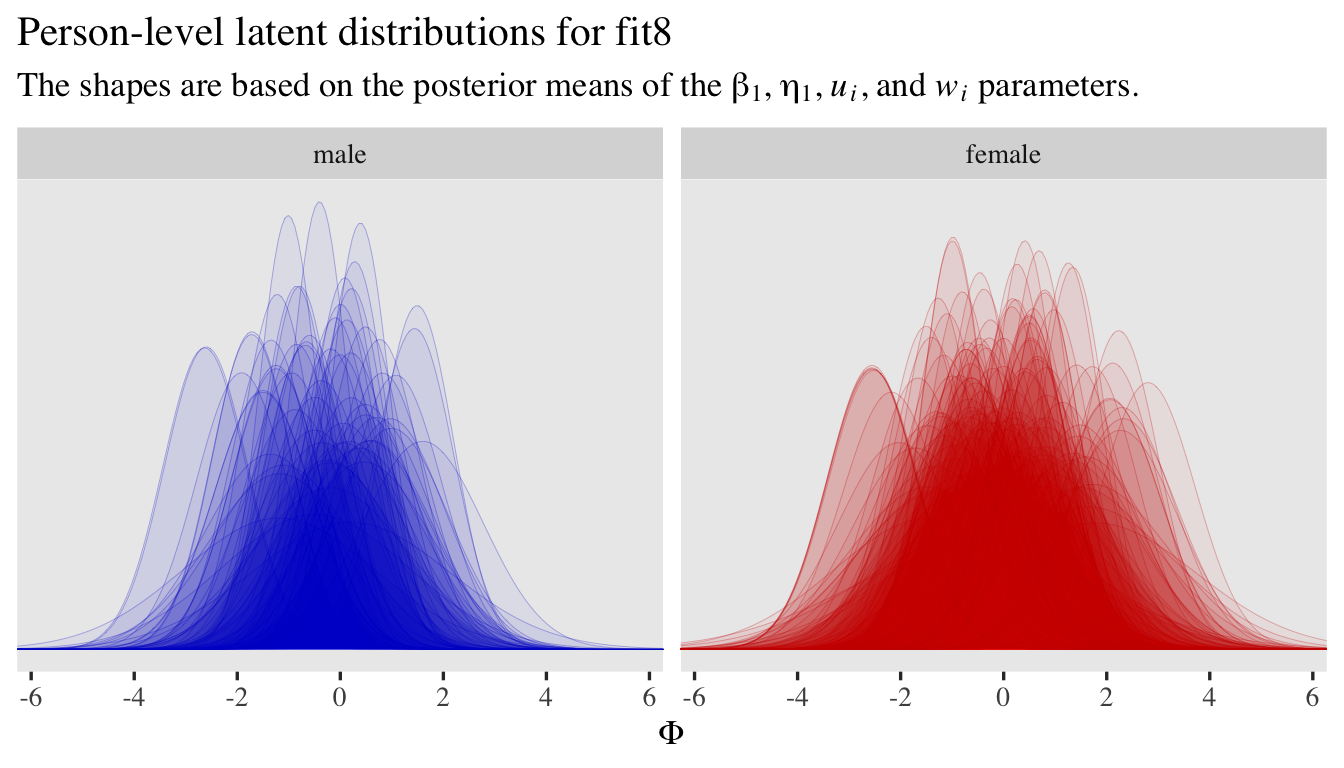

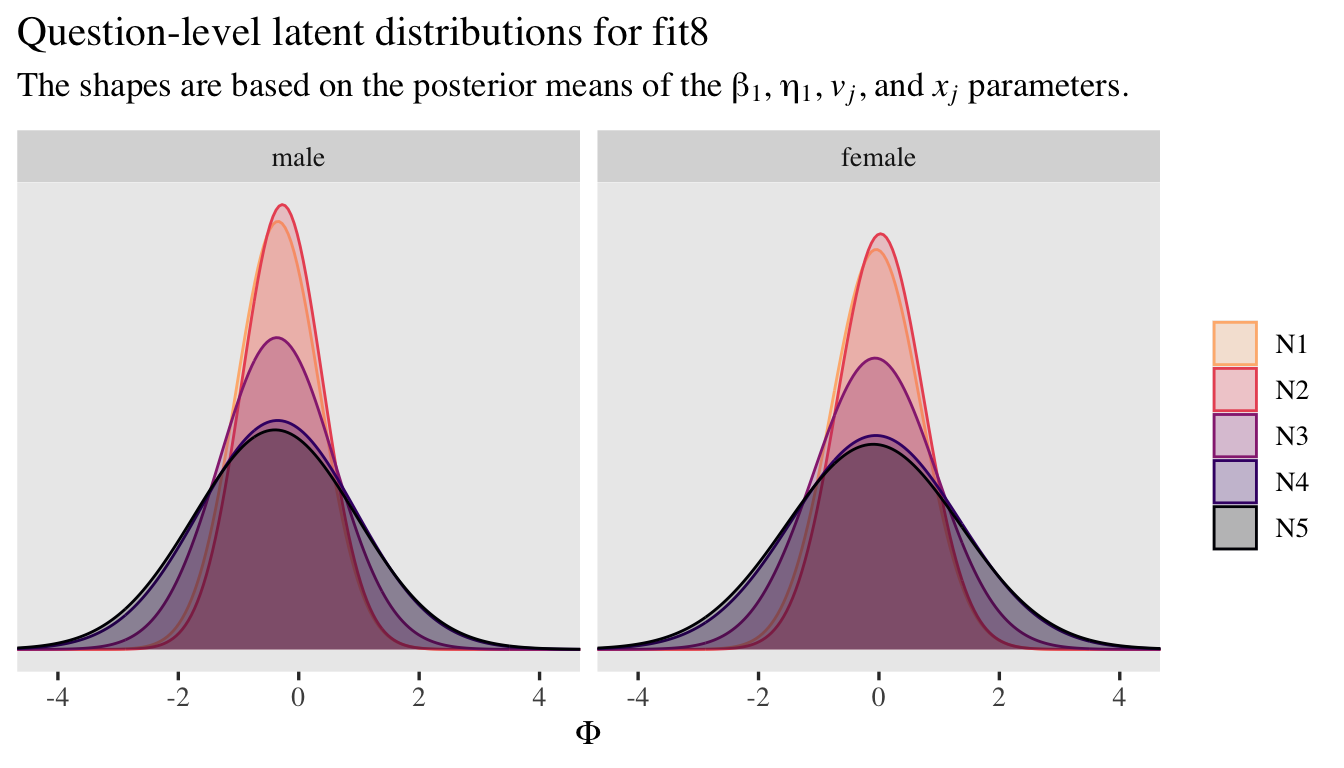

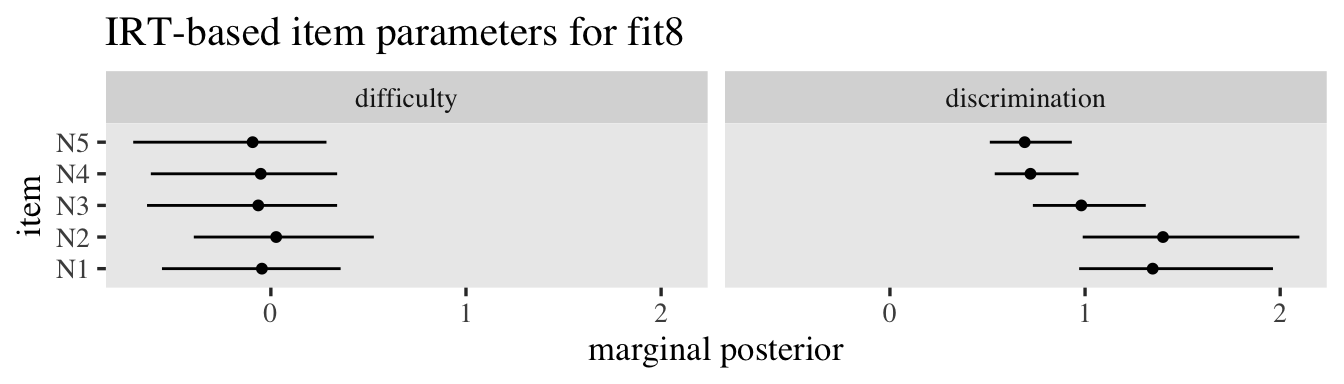

Full conditional distributional model.